Introduction

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms

(GEP-NENs) are a group of rare tumors originating from

neuroendocrine cells of the pancreas or of the gastrointestinal

tract and comprise well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs)

and poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs)

(1). Moreover, depending on the

hormone and amine secretion activity, GEP-NENs can be classified

into functional and non-functional neoplasms (2). They represent the second most common

cancer of the digestive system as their incidence has increased

over the last decades (3). GEP-NENs

are characterized by an indolent behavior in terms of tumor growth

and the treatment of choice in locally defined tumors remains

surgical resection (4). However, at

presentation, ~80% of patients have already developed liver or

lymph node metastases (5). The

number of targeted and theranostic options for patients with NETs

have expanded significantly over the last decade; however, the

cytoreductive capacity of these agents remains quite modest

(6). Thus far, chemotherapy has

demonstrated to be clinically useful in patients with metastatic or

unresectable pancreatic NETs and grade 3 NET disease, however,

novel combination regimens and targeted therapy are necessary to

increase the number of cytotoxic options that may be relevant for

patients with NETs (6,7).

Numerous anticancer studies have focused lately on

natural compounds, present in fruits, vegetables and spices, that

exhibit pro-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory activity by targeting

diverse molecules including transcription factors, cytokines,

chemokines, growth factor receptors and inflammatory enzymes

(8). In addition, for their easy

availability, safety and relative low-cost, natural compounds are

particularly attractive for chemoprevention (8). Among the natural compounds, curcumin,

a hydrophobic polyphenol has been revealed to possess anticancer

properties along with an excellent safety profile although it

presents low solubility and bioavailability (9,10). To

circumvent this latter problem, a number of strategies have been

developed, involving the modification of its structure or

application of drug delivery agents, such as nanoparticles,

liposomes and micelles (11).

Another approach is based on the interaction of curcumin ligands

with inorganic or organometallic ruthenium moieties to provide more

soluble and assimilable compounds (12–14)

that are more attractive for clinical practice. Those compounds are

stable and water-soluble and their frameworks provide considerable

scope for optimizing the design in terms of their biological

activity and for minimizing side-effects. For these reasons,

organometallic ruthenium compounds are promising anticancer

molecules to be tested in clinical practice especially in

combination with other drugs (15–17).

It was recently demonstrated by the authors the anticancer effects

of ruthenium(II)-curcumin compounds in vitro in different

cancer cell lines including colon, breast and glioblastoma

(18,19), as well as their lack of toxicity in

normal cells (16). However, to the

best of the authors' knowledge, these compounds have never been

used in neuroendocrine tumors.

Different from normal cells, cancer cells often

activate an adaptive response to resist to the anticancer

treatments (20). In this regard,

the authors' recent studies demonstrated the role of the nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)-induced pathway as key

determinant in cancer cells' resistance to therapies (18,19,21).

NRF2 transcription factor is the master regulator of the oxidative

stress and its detoxifying activity is often hijacked by cancer

cells as a protective mechanism, particularly in the course of

anti-cancer treatments, leading to cancer cell resistance to

therapies (22). Among the NRF2

targets, involved in cancer progression and chemoresistance, is

heme-oxygenase 1 (HO-1), catalase, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1

(NQO1) and p62/SQSTM (herein p62) (22,23).

Intriguingly, NRF2 induces p62 expression and p62 stabilizes NRF2

by triggering the degradation of NRF2 inhibitor Kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), creating a positive feedback loop

between NRF2 and p62 that induces cancer progression and resistance

to therapies (24,25). NRF2 is often overexpressed in

pancreatic cancer which may reflect a greater intrinsic capacity of

the tumor cells to respond to stress signals and resist to the

chemotherapeutic agents (26).

However, to the best of the authors' knowledge, NRF2 activity has

never been evaluated in the pancreatic NET cell line BON-1, one of

the two commonly used human cell line GEP-NET-derived, which also

carries an endogenous dysfunctional p53 that inhibits apoptosis

(27–29). Among the oncogenic pathways that

establish a cross-talk with NRF2, other than p62, is mutant (mut)

p53 (30). Tumor suppressor p53

plays a central role in tumor prevention and in response to

anticancer therapies and, for these reasons, is the most

inactivated oncosuppressor in human tumors, by gene mutation or by

protein deregulation (31,32). TP53 gene mutations have been found

in pancreatic cancer affecting both cancer progression and response

to therapies (33), and also in

poorly differentiated NEC (34). In

BON-1 cell line, a homozygous stop-gain g.7574003A>G mutation

has been found in exon 10 of TP53 with possible inhibition of the

p53 apoptotic activity (28).

On the basis of the aforementioned background, in

the present study it was aimed to evaluate the anticancer effects

of the cationic Ruthenium (Ru)(II)-Bisdemethoxycurcumin compound

(Ru-bdcurc) in the cell line BON-1. The present study highlighted

the key role of NRF2 in BON-1 resistance to the cytotoxic activity

of the curcumin compound and the interplay of NRF2 with a

dysfunctional endogenous p53, supporting the monitoring of this

potential biomarker in neuroendocrine tumors for future assessment

of response to therapies.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

In the present study, the BON-1 cell line (RRUD:

CVCL_3985) (NCL2110P096; DBA Italia s.r.l.) (https:www.cellosaurus.org/CVCL_3985), established from

a lymph node metastasis of a human pancreatic carcinoid tumor

(27), was used. Cells arrived at

passage 1 and were used for additional 6 passages. Cells were

maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10%

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Corning, Inc.), plus

glutamine and antibiotics [Penicillin-Streptomycin-L-Glutamine,

100× (+) 29.2 mg/ml L-glutamine; cat. no. 30-009-CI; Merck KGaA] in

a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells

underwent routine testing to ensure that they were mycoplasm

negative. The cationic Ruthenium (Ru)(II) compound containing

bisdemethoxycurcumin and the hydrosoluble PTA phosphine

([(cym)Ru(bdcurc)(PTA)]SO3CF3) (where cym=cymene,

bdcurc=bisdemethoxycurcumin and

PTA=1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane) (herein Ru-bdcurc), with the

chemical formula: C36H42F3N3O7PRuS and the molecular weight: 849,8

g/mol, was synthesized as previously reported (16,17).

The Ru-bdcurc compound was dissolved in DMSO and stored at −20°C

before using it at 50 and 100 µM for the indicated times, as

previously reported (19). The

inhibitor of the antioxidant response Brusatol (cat. no. SML1868;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) (35,36)

was used at 100 µM for 4 h pre-treatment, as previously reported

(37).

Cell viability and colony assays

Cell viability was measured by Trypan blue (cat. no.

72571; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) assay. Subconfluent cells were

plated in six-well plates and, the day after, treated with

different concentration of Ru-bdcurc for 24 and 48 h or in

combinations with a 4 h pre-treatment of NRF2 inhibitor Brusatol

(100 nM). After treatments, both floating and adherent cells were

collected and stained with Trypan blue. Cell viability of

triplicates was assessed by counting blue (dead)/total cells with a

Neubauer hemocytometer using light microscopy. For long-term cell

survival, cells were plated in 60 mm Petri dishes until

subconfluence. Then, cells were mock-treated or treated with

Ru-bdcurc (50 or 100 µM) for 16 h. After treatments, cells were

washed, trypsinized, counted and equal cell number re-plated in

duplicate with fresh medium in 60-mm Petri dishes for determining

cell survival. Death-resistant colonies (with >50 cells) were

stained with crystal violet (cat. no. 46364; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) (diluted 1:2 with the cell culture) 14 days later. Plates

underwent scanning and the intensity of the cell staining was

quantified by ImageJ software.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and centrifuged and the

resulting pellets were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH

7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 1%

Nonidet P-40) (all from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) containing

protease inhibitors (CompleteTM, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail;

Merck Life Science S.r.l.). Protein concentration was determined by

the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (cat. no. 5000001; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.), a simple colorimetric assay for measuring

total protein concentration based on the Bradford dye-binding

method. Proteins were separated by loading 10–30 µg of total cell

lysates on denaturing 8–15% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis) gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), following

semidry blotting to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes

(Immobilon-P; Merck KGaA). Unspecific signals were blocked by

incubating the membranes in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1%

Tween 20 (TBS) and 3% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at

room temperature. Membranes were then probed with the primary

antibodies and subsequently with the following secondary

antibodies: Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (1:10,000; cat. no. 1706516) and

Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (1:10,000; cat. no. 1706515; both from Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The enzymatic signal was visualized by

chemiluminescence (ECL Detection system; Amersham; Cytiva). The

following antibodies were used: Mouse monoclonal anti-p62/SQSTM1

(D-3; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-28359), mouse monoclonal anti-catalase

(H-9; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-271803), mouse monoclonal anti-p53

(DO-1; 1:1,000; cat. no. sc-126), mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-2

(1:1,000; cat. no. sc-509) and mouse monoclonal anti-Mcl1 (G-7;

1:1,000; cat. no. sc-74437) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti-NRF2 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab62352;

Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-Histone H2AX (Ser139 clone

JBW301; 1:1,000; cat. no. 05-636; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA),

rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46; 1:200; ca.t no.

2855), rabbit polyclonal anti-4E-BP1 (1:200; cat. no. 9452; both

from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), mouse monoclonal

anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP, cleavage site-214-215;

1:1,000; cat. no. AB3565; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Mouse

monoclonal β-actin (Ab-1; 1:10,000; (cat. no. CP01; Calbiochem;

Merck KGaA), was used as protein loading control.

Densitometric analysis

Densitometry was performed on ECL results with

ImageJ software (1.47 version; National Institutes of Health) which

was downloaded from the NIH website (http://imagej,nih.gov/ij) and the relative band

intensity was normalized to β-actin signals and plotted as protein

expression/β-actin ratio.

Small interference (si)RNA

transfection

Cells were plated at subconfluency in 35-mm Petri

dishes and, the day after plating, were transfected with the Nrf2

small interference (si)RNA (cat. no. sc-37030) or control siRNA

(cat. no. sc-37007) (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; the

siRNA sequences are not available) using LipofectaminePLus reagent

(cat. no. 11514015; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as previously

reported (18). The concentration

used was 10 nmol. For p53 knockdown, cells were transfected with

sip53 plasmid (sip53) or an empty vector (si-ctr) (38,39)

using LipofectaminePLus reagent according to the manufacturer's

instructions. A total of 24 h after transfection, cells were

trypsinized and replated for the indicated experiments.

RNA extraction and semiquantitative

reverse transcription (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

analysis

Total RNA extraction was performed by using TRIzol

Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized by using MuLV

reverse transcriptase kit according to the manufacturer's

instructions (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was carried out with 2 µl cDNA reaction and

genes specific oligonucleotides under conditions of linear

amplification. by using Hot-Master Taq polymerase (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Primer sequences specific to the target genes

were as follows: HO-1 forward, 5′AAGATTGCCCAGAAAGCCCTGGAC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-AACTGTCGCCACCAGAAAGCTGAG-3′ (40) (annealing temperature: 58°C for 30

cycles); p62 forward, 5′-CTGCCCAGACTACGACTTGTGT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCAACTTCAATGCCCAGAGG-3′ (19,40)

(annealing temperature: 58°C for 28 cycles); NRF2 forward,

5′-TCCATTCCTGAGTTACAGTGTCT-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGGCTTCTGGACTTGGAACC-3′ (18,40,41)

(annealing temperature: 58°C for 30 cycles); MDR1 forward,

5′-AACGGAAGCCAGAACATTCC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGGCTTCCTGTGGCAAAGAG-3′

(42,43) (annealing temperature: 60°C for 29

cycles); 28S forward, 5′-GTTCACCCACTAATAGGGAACGTGA-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGATTCTGACTTAGAGGCGTTCAGT-3′ (39,40,44,45)

(annealing temperature: 58°C for 15 cycles); Bcl-2 forward,

5′-AGGATTGTGGCCTTCTTTGAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATCAAA-3′ (46)

(annealing temperature: 58°C for 30 cycles); and NOXA forward,

5′-AGGACTGTTCGTGTTCAGCTC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTCCACCTCCTGAGAAAACTC-3′

(47) (annealing temperature: 55°C

for 28 cycles). The denaturation and extension temperatures were,

respectively 98 and 72°C for all the mRNA amplifications. PCR

products were run on a 2% agarose gel and visualized with GelRed

Nucleic Acid gel stain (Biotium, Inc.). The housekeeping 28S gene,

used as internal standard, was amplified from the same cDNA

reaction mixture. Densitometric analysis was applied to quantify

mRNA levels compared with 28S control gene expression.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments and

statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism® software

(Version 9.0.0; Dotmatics). The unpaired two-tailed Student t-test

(for data containing two groups) and the nonparametric 1-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's HSD test (for

multiple comparisons tests) were used to demonstrate statistical

significance. A difference was considered statistically significant

when P≤0.05.

Results

Ru-bdcurc compound induces dose- and

time-dependent BON-1 cells' death

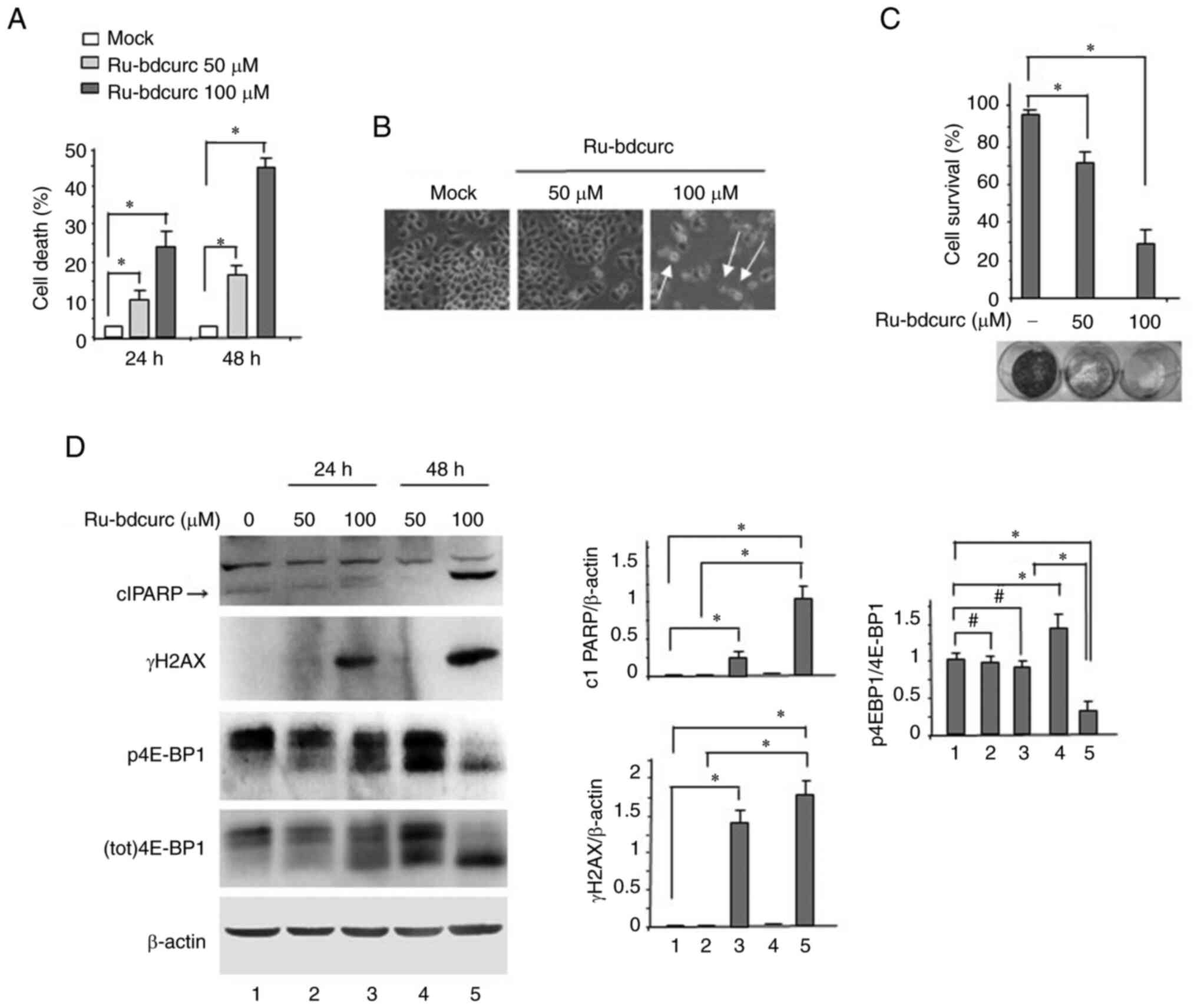

BON-1 cells were treated with two concentrations of

Ru-bdcurc compound that were recently demonstrated by the authors

to have different cytotoxic activity against colon cancer cells

(19). The results revealed a dose-

and time-dependent cell death, as indicated by the trypan blue

assay (Fig. 1A). Cell death was

also evidenced microscopically where distinct signs of cell

shrinkage were observed, in particular at 100 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc

(Fig. 1B). The EC50 for the

Ru-bdcurc compound was 100 µM (AAT Bioquest, Inc; http://www.aatbio.com/tools/ic50-calculator). Then the

long-term survival was analyzed by colony formation assay. The

results of the densitometric analysis demonstrated that 100 µM dose

of Ru-bdcurc significantly reduced BON-1 cell survival, compared

with 50 µM dose (Fig. 1C). At the

biochemical level, the occurrence of an apoptotic cell death, as

indicated by the cleaved fragment of PARP (clPARP) and by the

increased clPARP/PARP ratio, was evident only with the 100 µM dose

treatment, compared with 50 µM dose (Fig. 1D). The apoptotic cell death

associated with the appearance of the phosphorylated form of H2AX

(γH2AX) (Fig. 1D), a marker of DNA

damage and apoptosis (48). Then

the phosphorylation of 4EBP1 (p4E-BP1), a mTOR target whose

activation can sustain cancer cell survival and predict poor

prognosis (49,50), was investigated. In agreement, mTOR

pathway has been found dysregulated in GEP-NET and involved in

tumor development (51). As shown

in Fig. 1D, p4E-BP1 was induced by

50 µM dose, on the other hand, p4E-BP1 was impaired by 100 µM dose

of Ru-bdcurc. This latter result associated with the greater

induction of cell death that was observed by using 100 µM dose of

Ru-bdcurc, compared with 50 µM dose, strengthening the

antiapoptotic role of p4E-BP1. Collectively, these results

indicated that 100 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc induced BON-1 cell death

while 50 µM dose activated survival pathways that potentially

reduced the compound cytotoxic effects.

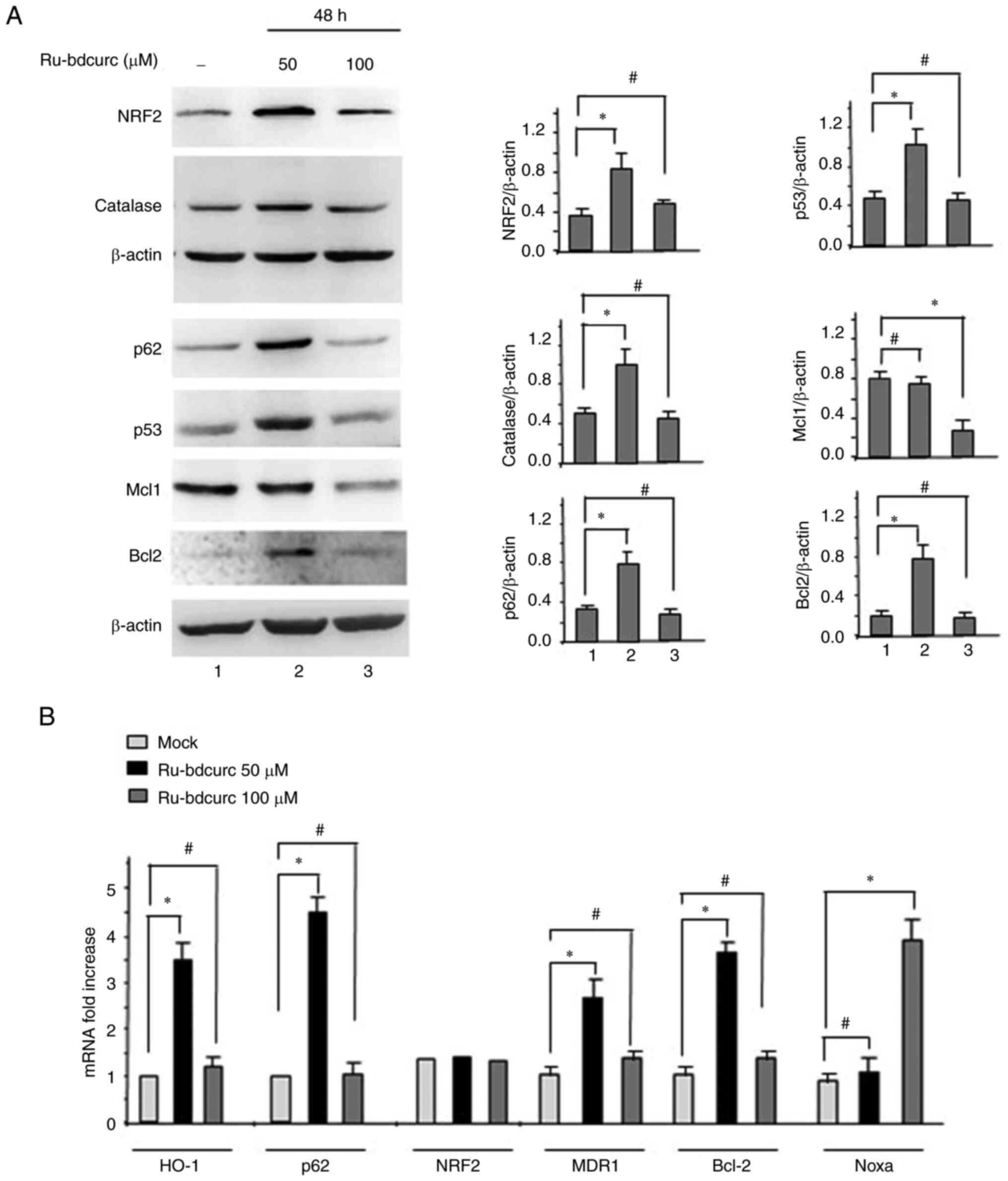

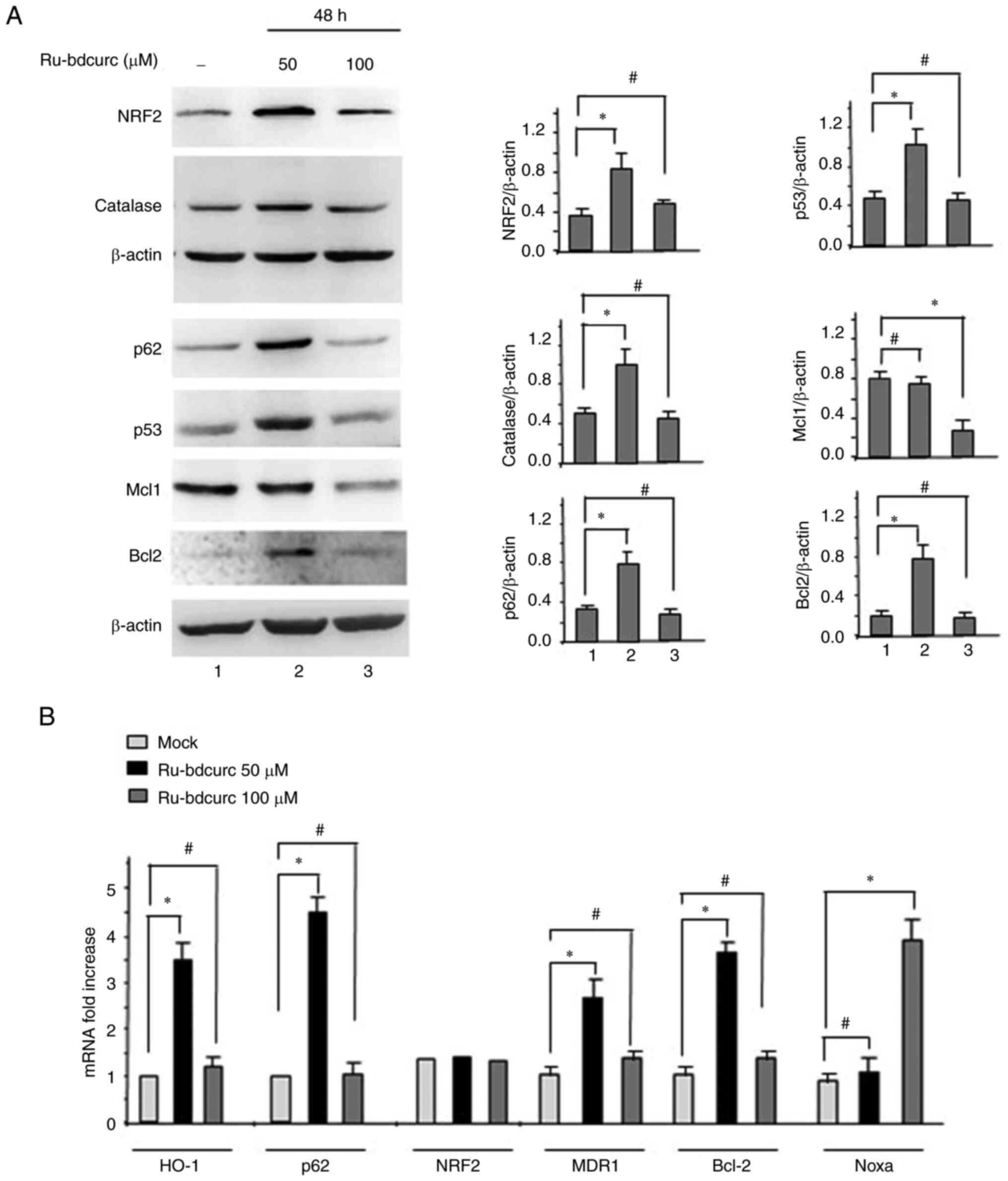

NRF2 pathway activation in response to

50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc

Several lines of evidence suggest the important role

of NRF2 in the chemoresistance of different types of cancer cells

(22), as also assessed by the

authors' recent studies using curcumin compounds (18,19).

However, to the best of the authors' knowledge, NRF2 has never been

evaluated in BON-1 cells. Therefore, the NRF2 pathway in BON-1

cells in response to the Ru-bdcurc treatment was next assessed. To

this aim, the two doses of the compound, that were revealed to have

different outcome in terms of cell death as aforementioned, were

used. The experimental data demonstrated that 50 µM dose of

Ru-bdcurc significantly increased the levels of NRF2 protein,

compared with the 100 µM dose, and induced the expression of its

targets such as catalase and p62 (Fig.

2A). To evaluate if the NRF2 induction was at the

transcriptional or post-transcriptional level, mRNA analysis was

performed. It was identified that 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc did not

induce NRF2 gene expression (Fig.

2B), suggesting rather stabilization of NRF2 at the protein

level. In addition, only the 50 µM dose increased the mRNA

expression of the NRF2 targets HO-1 and p62 (Fig. 2B), indicative of NRF2

transcriptional activation, in this setting. Thus, the increased

p62 gene expression was in accordance with the finding that p62 is

a NRF2 transcriptional target (23–25).

Interestingly, it has been reported that p62 activates pro-survival

pathways including mTOR (52), in

agreement with the aforementioned results in Fig. 1 and with the cross-talk among

oncogenic pathways such as p62/mTOR/NRF2 to increase tumor

development and resistance to therapies (30). In agreement with the different

extent of cell death in response to different doses of Ru-bdcurc,

the results showed that only 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc increased the

antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein levels while the 100 µM dose

significantly reduced the levels of Mcl1 protein (Fig. 2A), a pro-survival member of the

Bcl-2 family (53). Moreover, 50 µM

dose of Ru-bdcurc treatment, compared with 100 µM dose, increased

the endogenous p53 protein level (Fig.

2A), in agreement with the paradigm of NRF2/mutp53 interplay to

sustain their oncogenic activities (41,54).

The endogenous p53 is reported to be dysfunctional in BON-1 cells

and inhibit apoptosis (28). In

agreement, the present results revealed that 50 µM dose of

Ru-bdcurc, compared with 100 µM dose, induced the expression of

multidrug resistant gene 1 (MDR1), a target of some mutant p53

proteins (55), as well as of the

antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 (Fig. 2B),

which associated with a potential oncogenic activity of the

endogenous dysfunctional p53 in BON-1 cells. On the other hand, 100

µM dose of Ru-bdcurc induced the expression of Noxa (Fig. 2B), a pro-apoptotic gene induced by

p53 family members (56), that has

been shown to inhibit the antiapoptotic Mcl1 protein (57). This latter result is in consistency

with the reduction of Mcl1 protein levels in Fig. 2A and with induction of the apoptotic

cell death (Fig. 1A). Taken

together, these findings indicated that the Ru-bdcurc treatment was

able to induce pro-apoptotic (PARP cleavage, Fig. 1) or cell death-resistant pathways

(NRF2-induced targets, mTOR target 4E-BP1, Bcl-2 and dysfunctional

p53; Fig. 2) according to the low

(50 µM) or high (100 µM) dose used.

| Figure 2.NRF2 activation in response to

Ru-bdcurc. (A) BON-1 cells were treated with Ru-bdcurc (50 and 100

µM) for 48 h and the protein levels of NRF2, catalase, p62, p53,

Mcl1 and Bcl2 proteins were evaluated by western blot analysis;

β-actin was used as protein loading control and one representative

experiment is shown. The ratio of the protein levels vs. β-actin,

following densitometric analysis, is reported as histograms plus

SD. Statistics was measured between treated (50 or 100 µM) and the

untreated cells (−). (B) Total mRNA was extracted from cells

treated as in (A) to evaluate HO-1, NRF2, p62, MDR1, Bcl-2 and Noxa

gene expression by semiquantitative reverse transcription PCR of

reverse transcribed cDNA. Histograms represent the mean ± SD of

three independent experiments. Statistics was measured between

treated (50 or 100 µM) and the untreated cells (Mock).

*P≤0.05 and #, not statistically significant.

NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; Ru-bdcurc,

Ruthenium (Ru)(II)-Bisdemethoxycurcumin. |

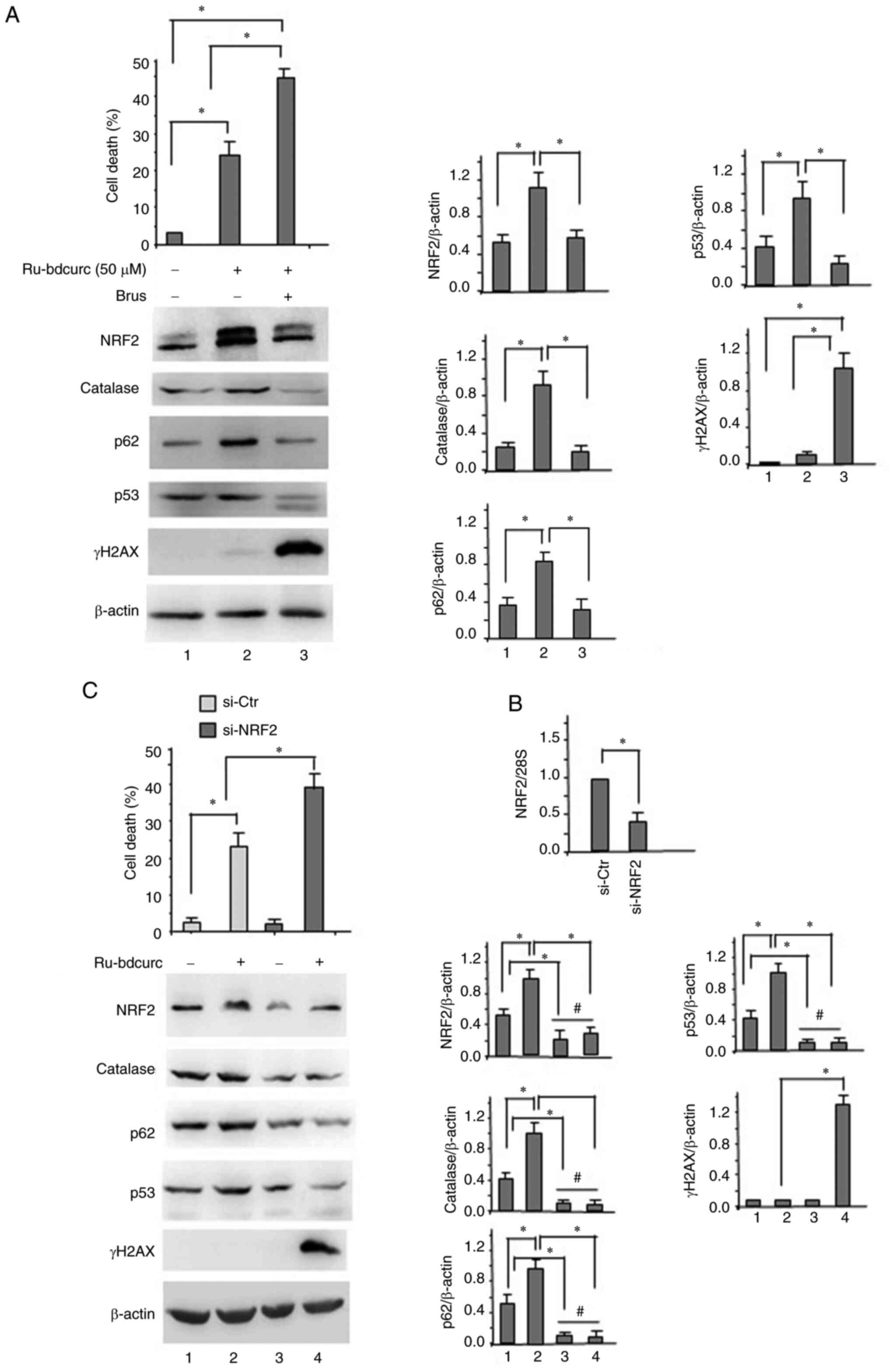

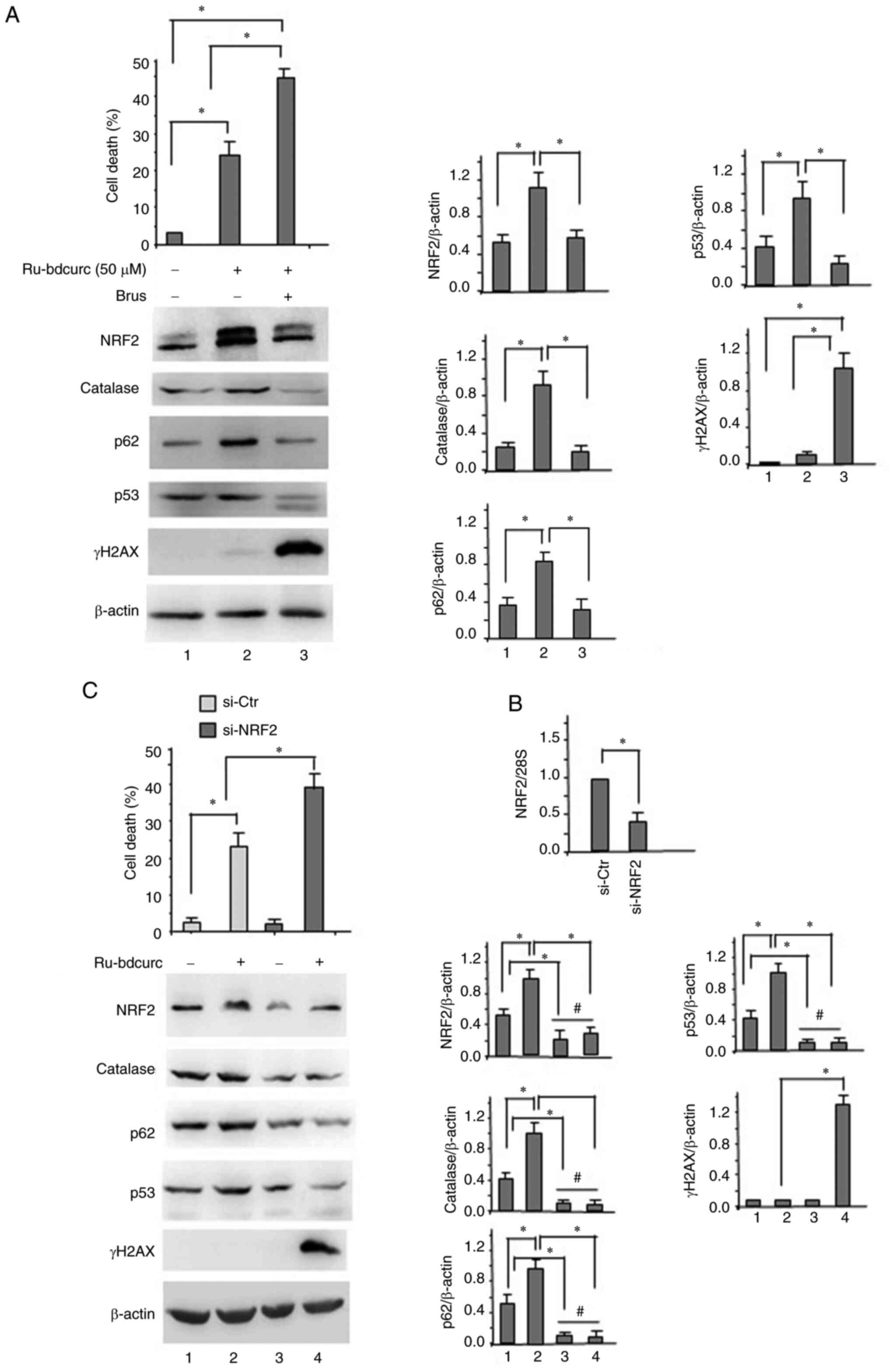

Targeting NRF2 improves the cytotoxic

activity of 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc

Then, to evaluate the biological role of NRF2 in

this setting, it was attempted to inhibit it by pharmacologic or

genetic means. NRF2 pharmacologic inhibitor Brusatol (35,36)

was used before exposing BON-1 cells to 50 µM of Ru-bdcurc. The

results demonstrated that the Ru-bdcurc/Brusatol combination

increased BON-1 cell death (Fig.

3A, upper panel), compared with the 50 µM dose Ru-bdcurc alone.

At the biochemical level, the Ru-bdcurc/Brusatol combination

counteracted the Ru-bdcurc-induced upregulation of NRF2 as well as

of its target p62 (Fig. 3A, lower

panels); in addition, the Ru-bdcurc/Brusatol combination

significantly increased the expression of γH2AX compared with the

50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc alone (Fig.

3A, lower panels). Similarly, knocking down NRF2 by specific

siRNA (Fig. 3B) increased the cell

death induced by 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc compound (Fig. 3C, left panels). At the biochemical

level, the NRF2 silencing reduced catalase and p62 expression, as

well as the p53 levels that were induced in response to 50 µM dose

of Ru-bdcurc (Fig. 3C, right

panels), suggesting that an interplay between NRF2 and

dysfunctional p53 exists in BON-1 cells. In addition, the

Ru-bdcurc/Brusatol combination significantly increased the

expression of γH2AX compared with the 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc alone

(Fig. 3C, lower panels).

Collectively, these results suggested that inhibiting the NRF2

pathway, induced by the lower dose of Ru-bdcurc, increased the

cytotoxic effect of Ru-bdcurc compound.

| Figure 3.Pharmacologic or genetic inhibition

of NRF2 improves the 50 µM Ru-bdcurc cytotoxic activity. (A) BON-1

cells were left untreated or pre-treated with 100 nM Brus for 4 h

and then treated with 50 µM Ru-bdcurc for 48 h, before cell

viability was measured by Trypan blue exclusion assay (upper

panel). Protein levels were evaluated by western blot analysis

(lower panel). β-actin was used as protein loading control and one

representative experiment is shown. The ratio of the protein levels

vs. β-actin, following densitometric analysis, is reported as

histograms plus SD (right panels). Statistics was measured between

treated (50 µM) and untreated cells (−) with or without Brus

co-treatment. (B) BON-1 cells were transfected with siRNA control

(si-ctr) or siNRF2 and, 24 h after transfection, NRF2 mRNA was

evaluated by semiquantitative reverse transcription PCR. (C) BON-1

cells, transfected as in (B) for siRNA interference, were treated,

24 h after siRNA transfection, with Ru-bdcurc (50 µM) for 48 h

before cell viability was measured by Trypan blue exclusion assay

(upper panel). Protein levels were evaluated by western blot

analysis (lower panel). β-actin was used as protein loading control

and one representative experiment is shown. The ratio of the

protein levels vs. β-actin, following densitometric analysis is

reported as histograms plus SD (right panels). Statistics was

measured between treated (50 µM) and untreated cells (−) and

compared according to NRF2 interference. *P≤0.05 and

#, not statistically significant. NRF2, nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2; Ru-bdcurc, Ruthenium

(Ru)(II)-Bisdemethoxycurcumin; Brus, brusatol; siRNA, small

interfering RNA. |

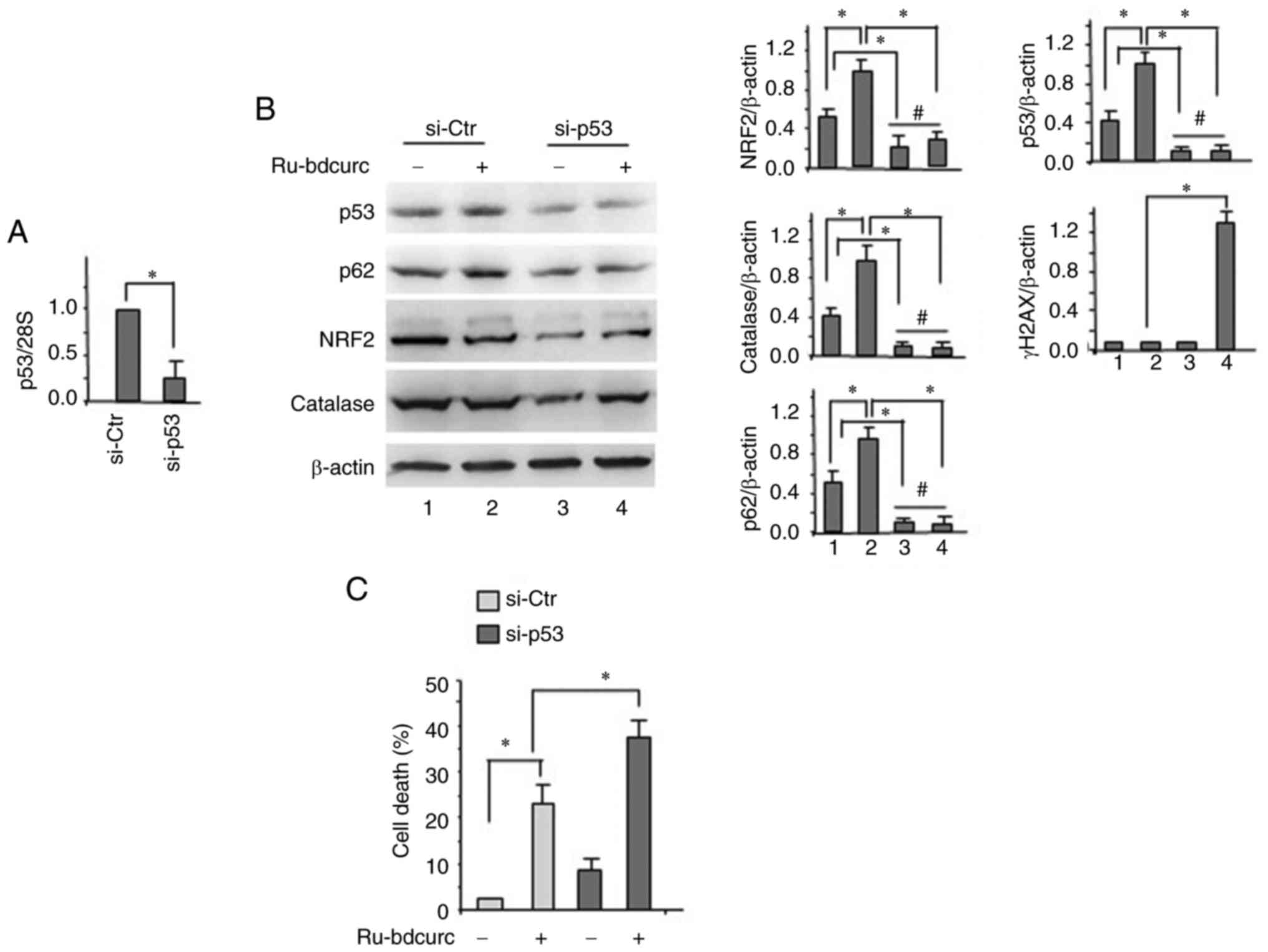

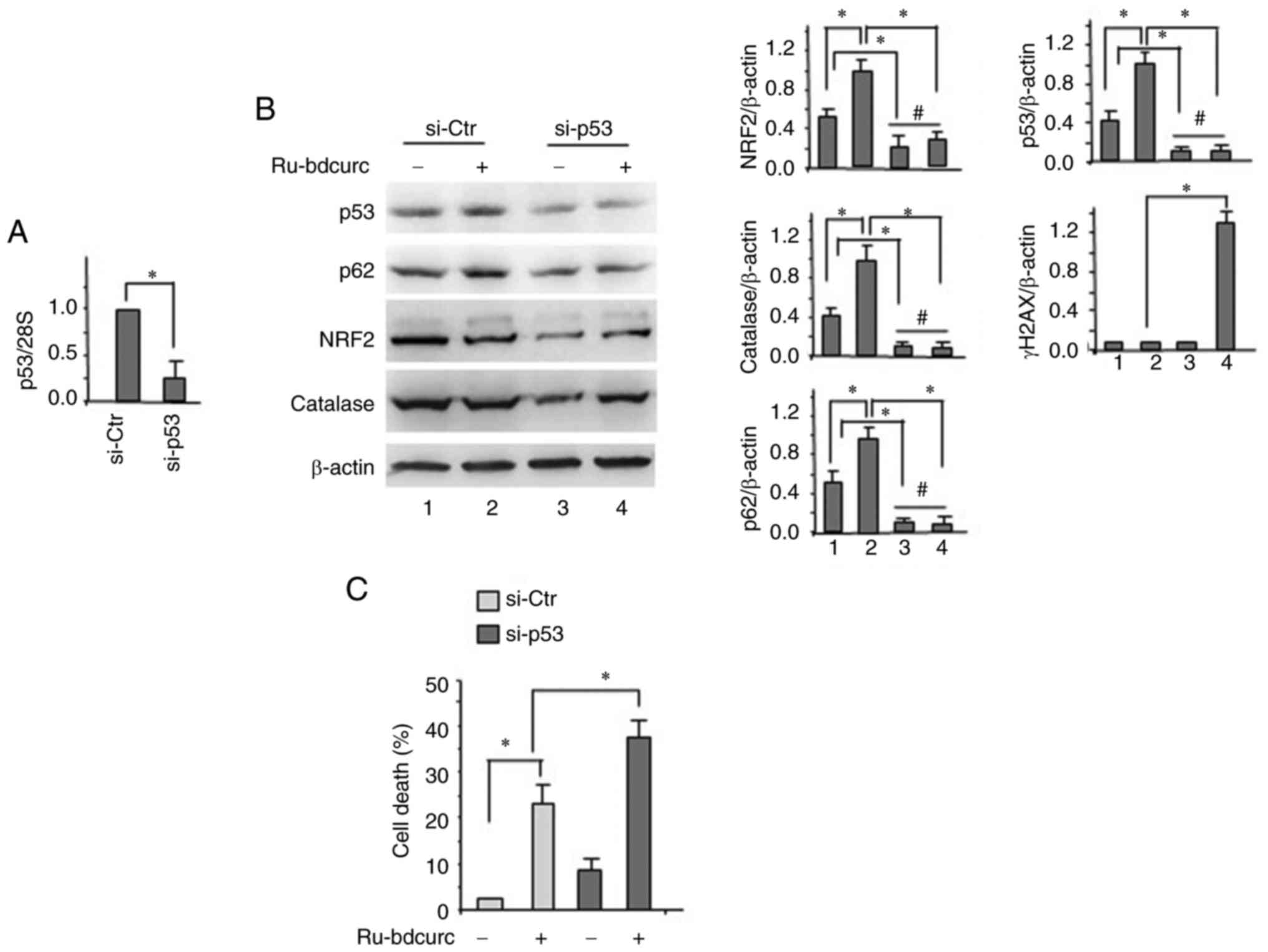

Targeting p53 reduces NRF2 activation

and increases the cytotoxic effect of 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc

Then, to evaluate the role of p53 in BON-1 cell

response to the Ru-bdcurc compound and its interplay with NRF2, it

was attempted to inhibit it by specific siRNA (38,39).

The results demonstrated that knocking down p53 (Fig. 4A) reduced the Ru-bdcurc-induced

upregulation of NRF2 and of its targets p62 and catalase (Fig. 4B). At the biological level, knocking

down p53 increased the cell death induced by 50 µM dose of

Ru-bdcurc (Fig. 4C). Taken

together, these results indicated that a dysfunctional endogenous

p53 in BON-1 contributed to cellular resistance to Ru-bdcurc

cytotoxicity, likely in an interplay with NRF2.

| Figure 4.Dysfunctional-p53 cross-talks with

NRF2 to reduce BON-1 chemosensitivity. (A) BON-1 cells were

transfected with siRNA control (si-ctr) and sip53 and, 24 h after

transfection, p53 mRNA was evaluated by semiquantitative reverse

transcription PCR. (B) BON-1 cells, transfected as in (A) for siRNA

interference were treated, 24 h after siRNA transfection, with

Ru-bdcurc (50 µM) for 48 h. Protein levels were evaluate by western

blot analysis. β-actin was used as protein loading control and one

representative experiment is shown. The ratio of the proteins level

vs. b-actin, following densitometric analysis, is reported as

histograms plus SD (right panels). (C) Trypan blue exclusion assay

was performed to asses viability of cells treated as in. (B)

Statistics was measured between treated (50 µM) and untreated cells

(−) and compared according to p53 interference. *P≤0.05 and

#, not statistically significant. NRF2, nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2; siRNA, small interfering RNA;

Ru-bdcurc, Ruthenium (Ru)(II)-Bisdemethoxycurcumin. |

Discussion

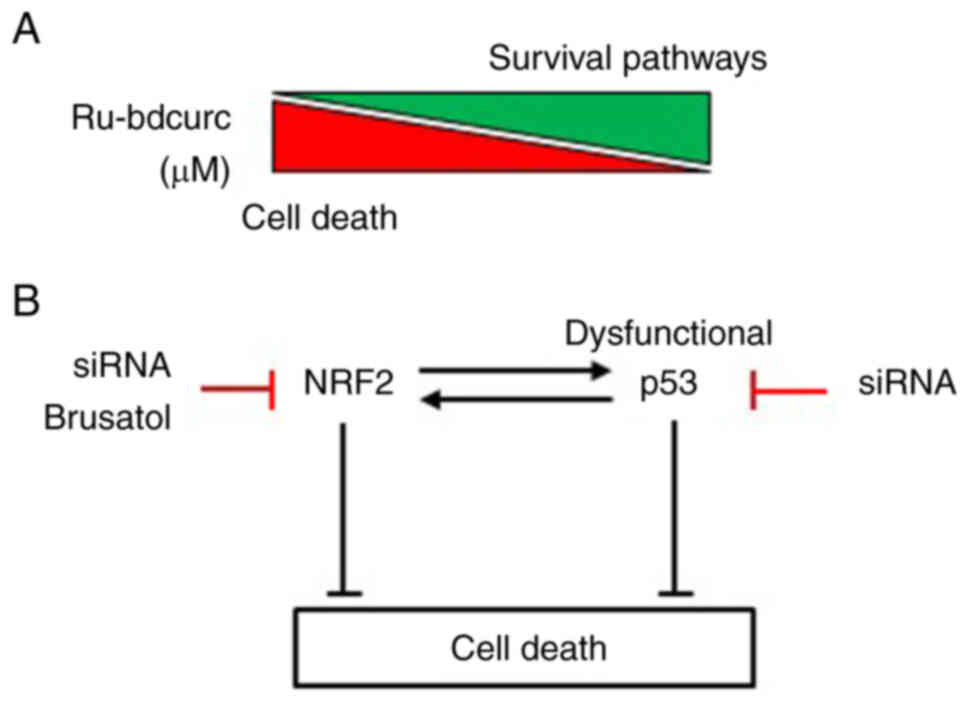

In the present study, it was revealed that the novel

Ru-bdcurc compound (16) was able

to induce cell death in the pancreatic NET cell line BON-1, in a

dose-dependent way (Fig. 5A).

Intriguingly, the higher dose of Ru-bdcurc (i.e., 100 µM) induced

apoptotic cell death while the lower dose (i.e, 50 µM) induced

chemoresistant pathways that reduced the cytotoxic activity of the

compound. The 100 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc treatment increased the

clPARP/PARP ratio, compared with 50 µM dose, and correlated with

the appearance of the phosphorylated form of H2AX (γH2AX), a marker

of DNA damage and apoptosis (48).

Moreover, 100 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc induced the expression of Noxa,

a pro-apoptotic gene induced by p53 family members (56), that has been reported to inhibit the

antiapoptotic Mcl1 protein (57),

in agreement with the reduction of Mcl1 protein levels in Fig. 2A. On the other hand, 50 µM dose of

Ru-bdcurc induced the phosphorylation of 4EBP1 (p4E-BP1), a mTOR

target whose activation can sustain cancer cell survival and

predict poor prognosis (49,50).

In agreement, mTOR pathway has been found to be dysregulated in

GEP-NET and involved in tumor development (51). The 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc activated

the NRF2 pathway with upregulation of its targets p62 and catalase,

increased the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein levels and the endogenous

dysfunctional p53 protein levels. The increased p62 gene expression

was in accordance with the finding that p62 is a NRF2

transcriptional target (23–25).

The reason why only the lower dose of Ru-bdcurc induced NRF2

activity remains not completely resolved at the molecular level.

From the literature it is known that curcumin can induce NRF2

through activation of p62 by phosphorylation (58), therefore it can be hypothesized that

only the lower dose of Ru-bdcurc might induce the kinases involved

in p62 posttranslational modifications in order to be activated.

Interestingly, it has been revealed that p62 activates pro-survival

pathways including mTOR (52), in

agreement with the aforementioned results in Fig. 1 and with the cross-talk among

oncogenic pathways such as p62/mTOR/NRF2 to increase tumor

development and resistance to therapies (30). Moreover, only the 50 µM dose of

Ru-bdcurc treatment, compared with 100 µM dose, increased the

endogenous p53 protein level, in agreement with the paradigm that

the interplay between NRF2 and mutp53 stabilizes each other

proteins to sustain their oncogenic activities (41,54).

The endogenous p53 has been reported to be dysfunctional in BON-1

cells and to inhibit apoptosis (28). Thus, in this study the wild-type p53

target genes were not detected after cell treatment with 50 µM dose

of Ru-bdcurc (data not shown), suggesting lack of p53 wild-type

activity. On the other hand, 50 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc, compared with

100 µM, induced the expression of MDR1, a target of some mutant p53

proteins (55), as well as of the

antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2, which associated with a potential

oncogenic activity of the endogenous dysfunctional p53 in BON-1

cells. Interestingly, 100 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc induced cell death

that correlated with the expression of Noxa a pro-apoptotic gene

induced by p53 but also by p53 family members such as p73 (56). The fact that p53 protein expression

did not increase after 100 µM dose of Ru-bdcurc but rather

decreased (Fig. 4B) can suggest

that mutant/dysfunctional p53 in BON-1 cells was downregulated in

agreement with NRF2 downregulation but that this downregulation did

not reactivate a potential endogenous wild-type p53 gene,

suggesting that p53 family members, rather than wild-type p53, were

inducing Noxa mRNA expression. However, further experiments are

necessary to validate the endogenous p53 status in BON-1 cells and

its or not reactivation after curcumin treatment. Mutations in p53

gene are reported in ~90–95% of GEP-NEC and in 3% of GEP-NET

(59); however, the endogenous

mutant p53 activity in BON-1 needs to be explored in future

studies. Inhibiting the NRF2 pathway by genetic or pharmacologic

means increased the cytotoxic effect of the lower dose of the

Ru-bdcurc compound. Similarly, silencing of the endogenous

dysfunctional p53 counteracted the NRF2 activation in response to

the lower dose of Ru-bdcurc and increased the cytotoxic effect of

the compound, strongly supporting the oncogenic interplay between

NRF2 and p53 in this setting (Fig.

5B). GEP-NEN are extremely heterogeneous tumors and identifying

potential biomarkers for therapeutic purpose is difficult. In the

present study, one potential pathway of chemoresistance to be

validated in tumor samples, was suggested. However, the limitation

of the present study is the use of only one cell line, despite the

cell lines available for this type of tumors are only two (27–29).

It was also attempted to perform the experiments in the QGP-1 cell

line but it was not possible not obtain the same results as in

BON-1. QGP-1 cell line carries a wtp53 but does not present NRF2

induction after treatment, as observed in BON-1 cells, at least in

the present experiments. Given that these tumors are genetically

different it becomes very difficult to generalize the results

between the two cell lines. Therefore, additional studies are

necessary to clearly establish a role for NRF2 and the

interconnected oncogenic molecular pathways in tumors in

vivo.

The results of the present study can be discussed in

view of the potential effects of curcumin treatment in patients; In

particular, the low versus the high dose of curcumin that can be

achieved in vivo in patients. Thus, in clinical trials high

dose of curcumin ends often in low plasma level of curcumin

(60,61) likely due to curcumin low solubility

and bioavailability and low curcumin doses have been shown to act

as an antioxidant agent and do not induce cell death, thus

contributing to acquired chemoresistance (62). For this reason, the use of more

soluble and assimilable compounds such as the organometallic

ruthenium ones (12–14), used in the present study, could be

taken in consideration in clinical practice. On the other side,

combination therapies with curcumin compounds and more classical

chemotherapeutic agents should include also molecules that target

the NRF2 pathway to inhibit not only NRF2 but also the

interconnected oncogenic pathways that often interact with it to

increase tumor resistance to therapies. In agreement, previous

studies have reported that targeting NRF2 is a promising strategy

for the treatment of several aggressive cancers where the

activation of the NRF2 pathway protects cancer cells from the

cytotoxic effects of the chemotherapeutic drugs (63–66).

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrated for

the first time, to the best of the authors' knowledge, that NRF2

may play a role in chemoresistance of the pancreatic neuroendocrine

BON-1 cancer cells and suggested to evaluate the NRF2-dependent

pathway as a potential biomarker in GEP-NENs tissues. If this

hypothesis is confirmed in GEP-NENs, NRF2 pathway could become a

novel biomarker to be taken in consideration to tailor more

effective cytotoxic therapies against this type of rare tumor that

remains an orphan-drug cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Elisa Melucci

(Regina Elena National Cancer Institute; Rome, Italy) for technical

support.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Italian Association for

Cancer Research (AIRC) (grant nos. Id16742 and Id23040) and by the

University of Camerino (Fondo di Ateneo per la Ricerca-University

Research; grant no: 2018).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

GDO, AG, MC, SS, MA, RP and FM conceptualized the

study. RP and FM developed methodology. AG, LM, GP, IV and GDO

curated data. GDO wrote the original draft. GDO, AG. MC, SS and FM

wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. GDO, SS and FM

supervised the study. GDO, MC and FM acquired funding. AG and LM

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rindi G, Mete O, Uccella S, Basturk O, La

Rosa S, Brosens LAA, Ezzat S, de Herder WW, Klimstra DS, Papotti M

and Asa SL: Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of

Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 33:115–154. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cives M and Strosberg JR:

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. CA Cancer J Clin.

68:471–487. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Huguet I, Grossman AB and O'Toole D:

Changes in the epidemiology of neuroendocrine tumours.

Neuroendocrinology. 104:105–111. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Norton JA: Surgery for primary pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 10:327–331. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Akirov A, Larouche V, Alshehri S, Asa SA

and Ezzat S: Treatment options for pancreatic neuroendocrine

tumors. Cancers. 11:8282019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Das S, Al-Toubah T and Strosberg J:

Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine tumors. Cancers. 13:48722021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dai M, Mullins CS, Lu L, Alsfasser G and

Linnebacher M: Recent advances in diagnosis and treatment of

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J

Gastrointest Surg. 14:383–396. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Haque A, Brazeau D and Amin AR:

Perspectives on natural compounds in chemoprevention and treatment

of cancer: An update with new promising compounds. Eur J Cancer.

149:165–183. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Patel SS, Acharya A, Ray RS, Agrawal R,

Raghuwanshi R and Jain P: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of

curcumin in prevention and treatment of disease. Crit Rev Food Sci

Nutr. 60:887–939. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zoi V, Galani V, Lianos GD, Voulgaris S,

Kyritsis AP and Alexiou GA: The role of curcumin in cancer

treatment. Biomedicines. 9:10862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Stohs SS, Chen O, Ray SD, Ji J, Bucci LR

and Preuss HG: Highly bioavailable forms of curcumin and promising

avenues for Curcumin-Based research and application. Molecules.

25:13972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wanninger S, Lorenz V, Subhan A and

Edelmann FT: Metal complexes of curcumin-synthetic strategies,

structures and medicinal applications. Chem Soc Rev. 44:4986–5002.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Pagliaricci N, Pettinari R, Marchetti F,

Pettinari C, Cappellacci L, Tombesi A, Cuccioloni M, Hadiji M and

Dyson PJ: Potent and selective anticancer activity of half-sandwich

ruthenium and osmium complexes with modified curcuminoid ligands.

Dalton Trans. 51:13311–13321. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gobbo A, Pereira SAP, Biancalana L,

Zacchini S, Saraiva MLMFS, Dyson PJ and Marchetti F: Anticancer

ruthenium(II) tris(pyrazolyl)methane complexes with bioactive

co-ligands. Dalton Trans. 51:17050–17063. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bonfili L, Pettinari R, Cuccioloni M,

Cecarini V, Mozzicafreddo M, Angeletti M, Lupidi G, Marchetti F,

Pettinari C and Eleuteri AM: Arene-RuII complexes of curcumin exert

antitumor activity via proteasome inhibition and apoptosis

induction. Chem Med Chem. 7:2010–2020. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pettinari R, Marchetti F, Condello F,

Pettinari C, Lupidi G, Scopelliti R, Mukhopadhyay S, Riedel T and

Dyson PJ: Ruthenium(II)-Arene RAPTA type complexes containing

curcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin display potent and selective

anticancer activity. Organometallics. 33:3709–3715. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Caruso F, Pettinari R, Rossi M, Monti E,

Gariboldi MB, Marchetti F, Pettinari C, Caruso A, Ramani MV and

Subbaraju GVJ: The in vitro antitumor activity of

arene-ruthenium(II) curcuminoid complexes improves when decreasing

curcumin polarity. J Inorg. Biochem. 162:44–51. 2016.

|

|

18

|

Garufi A, Baldari S, Pettinari R,

Gilardini Montani MS, D'Orazi V, Pistritto G, Crispini A, Giorno E,

Toietta G, Marchetti F, et al: A ruthenium(II)-curcumin compound

modulates NRF2 expression balancing the cancer cell death/survival

outcome according to p53 status. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:1222020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Garufi A, Pettinari R, Marchetti F, Cirone

M and D'Orazi G: NRF2 and Bip interconnection mediates resistance

to the organometallic ruthenium-cymene bisdemethoxycurcumin complex

cytotoxicity in colon cancer cells. Biomedicines. 11:5932023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

D'Orazi G and Cirone M: Interconnected

adaptive responses: A way out for cancer cells to avoid cellular

demise. Cancers. 14:27802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Garufi A, Pistritto G, D'Orazi V, Cirone M

and D'Orazi G: The impact of NRF2 inhibition on drug-induced colon

cancer cell death and p53 activity: A pilot study. Biomolecules.

2:4612022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Rojo de la Vega M, Chapman E and Zhang DD:

NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell. 34:21–43. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jain A, Lamark T, Sjottem E, Bowitz Larsen

K, Awuh JA, Overvatn A, McMahon M, Hayes JD and Johansen T:

p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and

creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response

element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 285:22576–22591.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi

K, Kobayashi A, Ichmura Y, Sou YS, Ueno I, Sakamoto A, Tong KI, et

al: The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress

response transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1.

Nat Cell Biol. 12:213–23. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang T, Harder B, Rojo de la Vega M, Wong

PK, Chapman E and Zhang DD: p62 links autophagy and Nrf2 signaling.

Free Rad Biol Med. 88:199–204. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lister A, Nedjadi T, Kitteringham NR,

Campbell F, Costello E, Lloyd B, Copple IM, Williams S, Owen A,

Neoptolemos JP, et al: Nrf2 is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer:

Implications for cell proliferation and therapy. Mol Cancer.

10:372011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Evers BM, Ishizuka J, Townsend CM Jr and

Thompson JC: The human carcinoid cell line, BON. A model system for

the study of carcinoid tumors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 733:393–406. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Vandamme T, Peeters M, Dogan F, Pauwels P,

Van Assche E, Beyens M, Mortier G, Vandeweyer G, de Herder W, Van

Camp G, et al: Whole-exome characterization of pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumor cell lines BON-1 and QGP-1. J Mol Endocrinol.

54:137–47. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Luley KB, Biedermann SB, Kunstner A, Busch

H, Franzenburg S, Schrader J, Grabowsi P, Wellner U, Keck T,

Brabant G, et al: A comprehensive molecular characterization of the

pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell lines BON-1 and QGP-1. Cancers

(Basel). 12:6912020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Cirone M and D'Orazi G: NRF2 in cancer:

Cross-talk with oncogenic pathways and involvement in

gammaherpesviruses-driven carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci.

24:5952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Vousden HK and Prives C: Blinded by the

light: The growing complexity of p53. Cell. 137:413–31. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Muller PA and Vousden KH: Mutant p53 in

cancer: New functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell.

25:304–317. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Voutsadakis IA: Mutations of p53

associated with pancreatic cancer and therapeutic implications. Ann

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 25:315–327. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Vijayvergia N, Boland PM, Handorf E,

Gustafson KS, Gong Y, Cooper HS, Sheriff F, Astsaturov I, Cohen SJ

and Engstrom PF: Molecular profiling of neuroendocrine malignancies

to identify prognostic and therapeutic markers: A Fox Chase Cancer

Center Pilot Study. Br J Cancer. 115:564–570. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ren D, Villeneuve NF, Jiang T, Wu T, Lau A

and Toppin HA: Brusatol enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by

inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 108:1433–1438. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Olayanju A, Copple IM, Bryan HK, Edge GT,

Sison RL, Wong MW, Lai ZQ, Lin ZX, Dunn K, Sanderson CM, et al:

Brusatol provokes a rapid and transient inhibition of Nrf2

signaling and sensitizes mammalian cells to chemical toxicity

implications for therapeutic targeting of Nrf2. Free Rad Biol Med.

78:202–12. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Garufi A, Traversi G, Gilardini Montani

MS, D'Orazi V, Pistritto G, Cirone M and D'Orazi G: Reduced

chemotherapeutic sensitivity in high glucose condition: implication

of antioxidant response. Oncotarget. 10:4691–4702. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cecchinelli B, Lavra L, Rinaldo C,

Iacovelli S, Gurtner A, Gasbarri A, Ulivieri A, Del Prete F,

Trovato M, Piaggio G, et al: Repression of the antiapoptotic

molecule galectin-3 by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase

2-activated p53 is required for p53-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell

Biol. 26:4746–4757. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R and Agami R: A

system stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian

cells. Science. 296:550–553. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Garufi A, Giorno E, Gilardini Montani MS,

Pistritto G, Crispini A, Cirone M and D'Orazi G:

P62/SQSTM1/Keap1/NRF2 axis reduces cancer cells death-sensitivity

in response to Zn(II)-curcumin complex. Biomolecules. 11:3482021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lisek K, Campaner E, Ciani Y, Walerych D

and Del Sal G: Mutant p53 tunes the NRF2-dependent antioxidant

response to support survival of cancer cells. Oncotarget.

9:20508–20523. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gong C, Yao H, Liu Q, Chen J, Shi J, Su F

and Song E: Markers of tumor-initiating cells predict

chemoresistance in breast cancer. PLoS One. 5:e156302010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Garufi A, Pistritto G, Cirone M and

D'Orazi G: Reactivation of mutant p53 by capsaicin, the major

constituent of peppers. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 35:1362016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gilles C, Polette M, Mestdagt M,

Nawrocki-Raby B, Ruggeri P, Birembaut P and Foidart JM:

Transactivation of vimentin by beta-catenin in human breast cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 15:2658–2664. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Nodale C, Sheffer M, Jacob-Hirsch J,

Folgiero V, Falcioni R, Aiello A, Garufi A, Rechavi G, Givol D and

D'Orazi G: HIPK2 downregulates vimentin and inhibits breast cancer

cell invasion. Cancer Biol Ther. 13:198–205. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Garufi A, Trisciuoglio D, Porru M,

Leonetti C, Stoppacciaro A, D'Orazi V, AVantaggiati ML, Crispini A,

Pucci D and D'Orazi G: A fluorescent-based Zn(II)-complex

reactivates mutant (R175H and R272H) p53 in cancer cells. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 32:722013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Garufi A, Pucci D, D'Orazi V, Cirone M,

Bossi G, Avantaggiati ML and D'Orazi G: Degradation of mutant

p53H175 protein by Zn(II) through autophagy. Cell Death Dis.

5:e12712014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura

AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S and Pommier Y: Gamma H2AX and cancer.

Nat Rev Cancer. 8:957–967. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Miao Y, Chen L, Shi C, Fan R, Chen P, Liu

H, Xia A and Qin H: Increased phosphorylation of 4E-binding protein

1 predicts poor prognosis for patients with colorectal cancer. Mol

Med Rep. 15:3099–3104. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Gonnella R, Zarrella R, Santarelli R,

Germano CA, Gilardini Montani MS and Cirone M: Mechanisms of

sensitivity and resistance of primary effusion lymphoma to Dimethyl

Fumarate (DMF). Int J Mol Sci. 23:67732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zanini S, Renzi S, Giovinazzo F and

Bermano G: mTOR pathway in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

tumor (GEP-NETs). Front Endocrinol. 11:5625052020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Moscat J, Karin M and Diaz-Meco MT: p62 in

cancer: Signaling adaptor beyond autophagy. Cell. 167:606–609.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Widden H and Placzek WJ: The multiple

mechanisms of Mcl1 in the regulation of cell fate. Commun Biol.

4:10292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Gilardini Montani MS, Cecere N, Granato M,

Romeo MA, Falcinelli L, Ciciarelli U, D'Orazi G, Faggioni A and

Cirone M: Mutant p53, stabilized by its interplay with HSP90,

activates a positive feed-back loop between NRF2 and p62 that

induces chemo-resistance to Apigenin in pancreatic cancer cells.

Cancers. 11:7032019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sampath J, Sun D, Kidd VJ, Grenet J,

Gandhi A, Shapiro LH, Wang Q, Zambetti GP and Schuetz JD: Mutant

p53 cooperates with ETS and selectively up-regulates human MDR1 not

MRP1. J Biol Chem. 276:39359–39367. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Martin AG, Trama J, Crighton D, Ryan KM

and Fearnhead HO: Activation of p53 and induction of Noxa by DNA

damage requires NG-kappa B. Aging (Albany NY). 1:335–349. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Chiou JT, Huang NC, Hiang CH, Wang LJ, Lee

YC, Shi YJ and Chang LS: NOXA-mediated degradation of MCL1 and

BCL2L1 causes apoptosis of daunorubicin-treated human acute myeloid

leukemia cells. J Cell Physiol. 236:7356–7375. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Park JY, Sohn HY, Koh YH and Jo C:

Curcumin activates Nrf2 through PKCd-mediated p62 phosphorylation

at Ser351. Sci Rep. 11:84302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Kawasaki K, Fujii M and Sato T:

Gastroenteroepatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: Genes, therapies and

models. Dis Model Mech. 11:dmm0295952018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Cao J, Jia L, Zhou HM, Liu Y and Zhong LF:

Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage induced by curcumin in human

hepatoma G2 cells. Toxicol. 91:476–483. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Kunati SR, Yang SM, William BM and Xu Y:

An LC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determination of curcumin,

curcumin glucuronide and curcumin sulfate in a phase II clinical

trial. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 156:189–198. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Giordano A and Tommonaro G: Curcumin and

Cancer. Nutrients. 11:23762019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Arena A, Romeo MA, Benedetti R, Gilardini

Montani MS, Santarelli R, Gonnella R, D'Orazi G and Cirone M: NRF2

and STAT3: Friends or foes in carcinogenesis? Discov Oncol.

14:372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Sajadimajd S and Khazaei M: Oxidative

stress and cancer: The role of Nrf2. Curr Cancer Drug Targtes.

18:538–557. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

No JH, Kim YB and Song YS: Targeting Nrf2

signaling to combat chemoresistance. J Cancer Prev. 19:111–117.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Torrente L and DeNicola GM: Targeting NRF2

and its downstream processes: Opportunities and challenges. Annu

Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 62:279–300. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|