Introduction

A keloid is defined as an overgrowth of pathological

scar tissue that grows beyond the original boundaries of the wound,

does not regress spontaneously and tends to recur despite treatment

(1,2). It can also spread to the surrounding

skin by invasion (3). The clinical

feature of keloid is a raised growth, usually accompanied by pain

and pruritus (4). Since the

mechanism and etiopathogenesis of keloids remain unknown, keloid

therapy is very limited.

Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6) was

identified in differential screening of a cDNA library collected

from tumor necrosis factor-treated human diploid FS-4 fibroblasts

(5). Multiple functions of TSG-6

have been proposed, including interacting with matrix-associated

molecules or acting as an inflammatory factor (6,7).

However, current knowledge on the physiological function of TSG-6

remains limited. It has been reported to be critical in maintaining

the physiological architecture of skin (8). Furthermore, TSG-6 has potent

anti-inflammatory properties, which have been investigated in

several disease models, such as rheumatoid arthritis (9,10).

In our previous rabbit ear model of hypertrophic scarring,

injection of TSG-6 protein into the wound resulted in reduced

hypertrophic scar formation and anti-inflammatory effects during

wound healing (11). However, the

role of TSG-6 in keloid remains unclear.

In the current study, a TSG-6 expression vector was

constructed and stably transfected into human keloid fibroblasts

(KFs). The effects of overexpression of TSG-6 on proliferation and

apoptosis in KFs were determined. In addition, the potential

mechanisms of the signaling pathway regulated via TSG-6 in KFs were

investigated.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The current study was approved by the institutional

review board of Anhui Medical University (Hefei, China), and

written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to

inclusion. The study was performed according to the principles of

the Declaration of Helsinki.

Keloid fibroblasts and cell

culture

Ten patients were recruited from the First

Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. The

characteristics of participants with keloid in this study are

listed in Table I. Patients had

received no previous treatment for keloid. KFs were isolated and

cultured as previously described (12). Cells were cultured in Dulbeccos

modified Eagles medium (DMEM), L-glutamine, 100 µg/ml streptomycin,

100 U/ml penicillin and fetal calf serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). No morphological and

biochemical differences were found with the passage.

| Table I.Patient information. |

Table I.

Patient information.

| Patient number | Sex | Age | Position | Cause of scar |

|---|

| 01 | Male | 03 | Anterior neck | Scald |

| 02 | Female | 05 | Chest | Scald |

| 03 | Female | 06 | Shoulder | Burn |

| 04 | Female | 09 | Back | Surgery |

| 05 | Male | 14 | Chest | Burn |

| 06 | Female | 18 | Earlobe | Puncture |

| 07 | Female | 19 | Earlobe | Puncture |

| 08 | Male | 23 | Upper Arm | Surgery |

| 09 | Female | 25 | Abdomen | Surgery |

| 10 | Female | 27 | Earlobe | Puncture |

Lentiviral vector construction and

packaging

Total RNA was extracted from KFs using TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to

the manufacturers instructions. cDNA synthesis was conducted

according to the RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit protocol

(Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). The TSG-6 cDNA (GenBank no.

AJ421518) was amplified by PCR (Takara Bio, Inc.) from KF cDNA

using the following oligonucleotide primers: Forward,

5′-GGAATTCATGATCATCTTAATTTACT-3; and reverse,

5′-CGGGATCCTAAGTGGCTAAATCTTCC-3. The cycling for PCR amplifying

reaction was: Reverse transcription (RT) 50°C, 5 min for 1 cycle;

RT inaction 95°C, 20 sec for 1 cycle; denaturing 95°C, 15 sec for

40 cycles; annealing 60°C, 60 sec for 40 cycles. Sequencing results

were analyzed using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) from

National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD, USA).

The amplified DNA was digested by the enzymes EcoRI and

BamHI and ligated into lentiviral plasmid pLVX-Puro

(Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Following

transduction of DH5α-competent E. coli, the positive clones

were selected for PCR identification and DNA sequencing. Clones

containing the target plasmids were selected and named

pLVX-Puro-TSG-6.

pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 was highly purified and extracted

with endotoxin-free solution. pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 was then

co-transfected into 293T cells (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) with

pHelper 1.0 (Biovector Science Lab, Inc., Beijing, China) and

pHelper 2.0 (Biovector Science Lab, Inc.) and lentiviruses using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

according to the manufacturers instructions. The 293T cells were

cultured using Minimum Essential Media (MEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5%

CO2. Cells were seeded at a concentration of

5×105 cells/well in 6 well plates. The plasmids were

mixed in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube with 1.5 µg Lentiviruses plus 1.5

µg packing vector (pLVX-Puro-TSG-6: pHelper 1.0: pHelper 2.0=5:3:2)

and 125 µl MEM medium, then 5 µl Lipo in 125 µl MEM added. The Lipo

and plasmids mixture was mixed and incubated for 20 min at 25°C.

During the incubation of the Lipo and plasmids mixture, the culture

medium of the 293T cells was replaced with fresh MEM medium. Then

the transfection mixture was added to the well, and it was moved to

an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. At 8 h following

transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh growth medium.

After culture for 48 h, the supernatant containing lentivirus

particles was collected and centrifuged at 1,258 × g for 5 min, and

cell debris was discarded. In order to obtain a high concentration

of lentivirus, the supernatant was further filtered to remove cells

and debris. The virus titer in 293T cells was determined by

end-point dilution assay.

Infection with recombinant

lentiviruses

KFs in logarithmic growth phase were divided into

three groups: pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 group, pLVX-Puro group and KFs group.

In each group, 8×104 cells were seeded into a 6-well

plate and cultured in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C

for 24 h. Following adhesion, the supernatant was discarded, and 2

ml DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was added. Once the cells reached 30% confluence,

the medium was removed. Subsequently, pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 or pLVX-Puro

were added into the wells at multiplicity of infection of 10.

Following the addition of 50 µl polybrene, DMEM containing 10%

fetal calf serum was added to reach a total of 2 ml. For the KF

group (2 wells), only 2 ml DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum was

added. Stable transfectants of pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 and pLVX-Puro were

continuously selected using 2.5 µg/ml puromycin. Stable

transfection was further confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR

(RT-PCR) and western blot analysis.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Levels of specific mRNAs in each group were assessed

by RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Purified RNA (1 µg)

was reverse transcribed using the RNA PCR Kit (Takara Biotechnology

Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) according to the manufacturers protocol.

PCR primers are listed in Table

II. cDNA was amplified and quantified using the RT-PCR Kit and

the following conditions: 94°C for 5 min, then 40 cycles consisting

of 30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 54°C and 45 sec at 72°C, followed by

incubation at 72°C for 10 min.

| Table II.Oligonucleotides used in

reverse-polymerase chain reaction analysis. |

Table II.

Oligonucleotides used in

reverse-polymerase chain reaction analysis.

| Gene | Forward (5–3) | Reverse (5–3) |

|---|

| p21 |

CGTGAGCGATGGAACTTCGA |

CTCTTGGAGAAGATCAGCCG |

| Cyclin D1 |

CCCTCGGTGTCCTACTTCA |

CTCCTCGCACTTCTGTTCCT |

| Bax |

GACGGCCTCCTCTCCTACTT |

CTCAGCCCATCTTCTTCCAG |

| Bcl-2 |

GAACTGGGGGAGGATTGTGG |

CCGTACAGTTCCACAAAGGC |

| Caspase-3 |

TGGAATTGATGCGTGATGTT |

GTCGGCATACTGTTTCAGCA |

| NF-κB |

AAGATCAATGGCTACACAGG |

CCTCAATGTCCTCTTTCTGC |

| β-actin |

CTCCATCCTGGCCTCGCTGT |

GCTGTCACCTTCACCGTTCC |

PCR products with UltraPure Ethidium bromide (EB;

Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were electrophoresed on

a 2% agarose gel. An image of the gel was captured and the

intensity of the bands was analyzed using Labworks software (UVP;

LLC, Phoenix, AZ, USA). β-actin was used as the internal loading

control.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was prepared using RIPA Lysis and

Extraction Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at freezing

temperature (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA).

Protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid assay

protein concentration kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Equal amounts of cell lysate (50 µg of protein) were boiled for 5

min and resolved by SDS-PAGE (12%), then electrophoretically

transferred onto a nitro-cellulose membrane. The membrane was

blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween

(TBST) overnight at 4°C, then incubated with appropriate primary

antibodies: TSG-6 (cat. no. ab128266; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA;

1:1,000); p21 (cat. no. 2947; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.;

1:1,000); cyclin D1 (cat. no. 2978; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.; 1:1,000); apoptosis regulator Bcl-2-associated X protein

(Bax; cat. no. 5023; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1,000);

apoptosis regulator B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2; cat. no. 2872; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1,000); caspase-3 (cat. no. 9662;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1,000); nuclear factor-κB

(NF-κB; cat. no. 8242; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1,000);

GAPDH (cat. no. 5174; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1,000);

β-actin (cat. no. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:1,000)

in blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature or 8–12 h at 4°C.

Following washing with TBST, the membranes were then incubated with

appropriate secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit; cat. no. 7074;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:10,000) for 3 h at room

temperature. After washing with TBST, proteins were visualized

using an enhanced chemiluminescence assay kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Grey scale scanning was used to analyze relative

expression by using Quantity One 1D Analysis software (version 4.4,

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

MTT assay

An MTT assay was performed to evaluate cell

proliferation of pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 transfected cells, pLVX-Puro

transfected cells and KFs. Single-cell suspensions

(1×105 cells/ml) were prepared for each group, and 100

µl cell suspension was seeded into 96-well plates and incubated at

37°C with 5% CO2 to form a monolayer. At 24 h, once

cells had adhered, 10 µl MTT stock solution (Promega Corporation,

Madison, WI, USA) was added to each well, and the plate was then

incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The MTT stock solution was discarded and

10 µl MTT solvent was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at

37°C to allow the crystals to be fully dissolved. The OD values at

570 nm were determined and the experiment was repeated three times.

Assay was also performed at 48, 72, 96 and 120 h after plating.

Flow cytometry assay

Flow cytometry was performed to evaluate apoptosis

and cell cycle arrest of the pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 transfected cells,

pLVX-Puro transfected cells and KFs. Cells in each group were

collected, digested with trypsin, washed with PBS three times, and

centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 560 × g, and the supernatant was

discarded. The cells were fixed with 70% ethanol at 4°C for ≥24 h

and then washed with PBS twice, following removal of ethanol by

centrifugation. Cell apoptosis was detected using Annexin V-FITC

Apoptosis Staining/Detection kit (Abcam). Cells (1×105)

were collected by centrifugation 4°C for 5 min at 560 × g and

re-suspended in 500 µl 1X binding buffer. Following incubation with

5 µl of Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and 5 µl of

propidium iodide (PI), the cells were maintained at room

temperature for 5 min in the dark. Apoptosis was detected using a

flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo 10.0.6 (FlowJo LLC,

Ashland, OR, USA).

For cell cycle analysis, cells from each group were

fixed in 70% ethanol for 1–3 h at 4°C. After washing with PBS,

cells were collected with RNase A and stained with PI for 15 min at

37°C. Cell cycle was analyzed with the flow cytometer, and the

distribution of all cell-cycle phases was determining with Modfit

Software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0

software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Tests for homogeneity of

variance (Levenes test) and one-way analysis of variance procedures

were performed, and followed by Turkeys multiple comparison post

hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Transfection efficiency

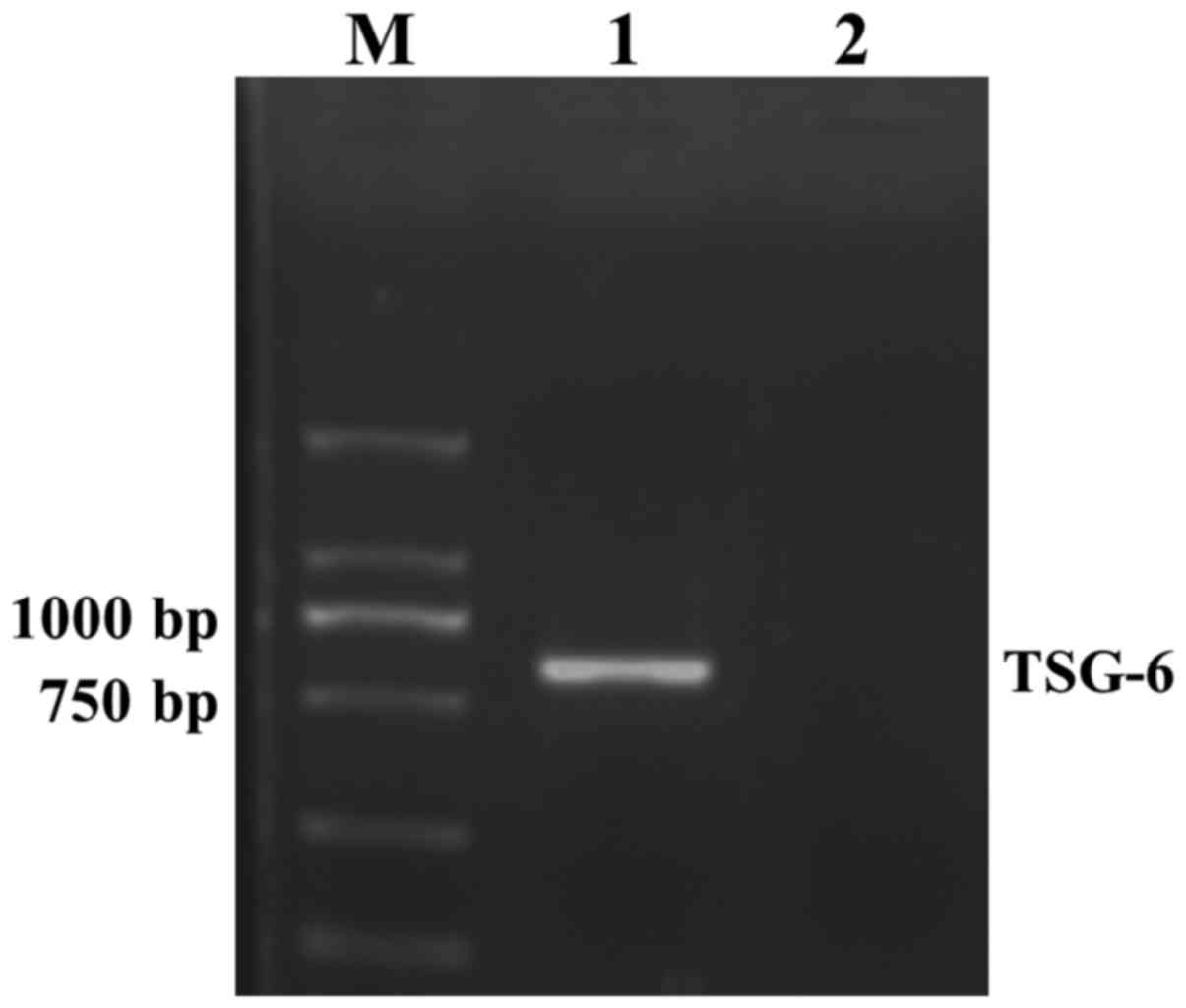

An 828 bp target gene fragment was obtained from

agarose gel electrophoresis of a PCR product, the size of which was

in accordance with TSG-6. The results suggested that TSG-6 gene was

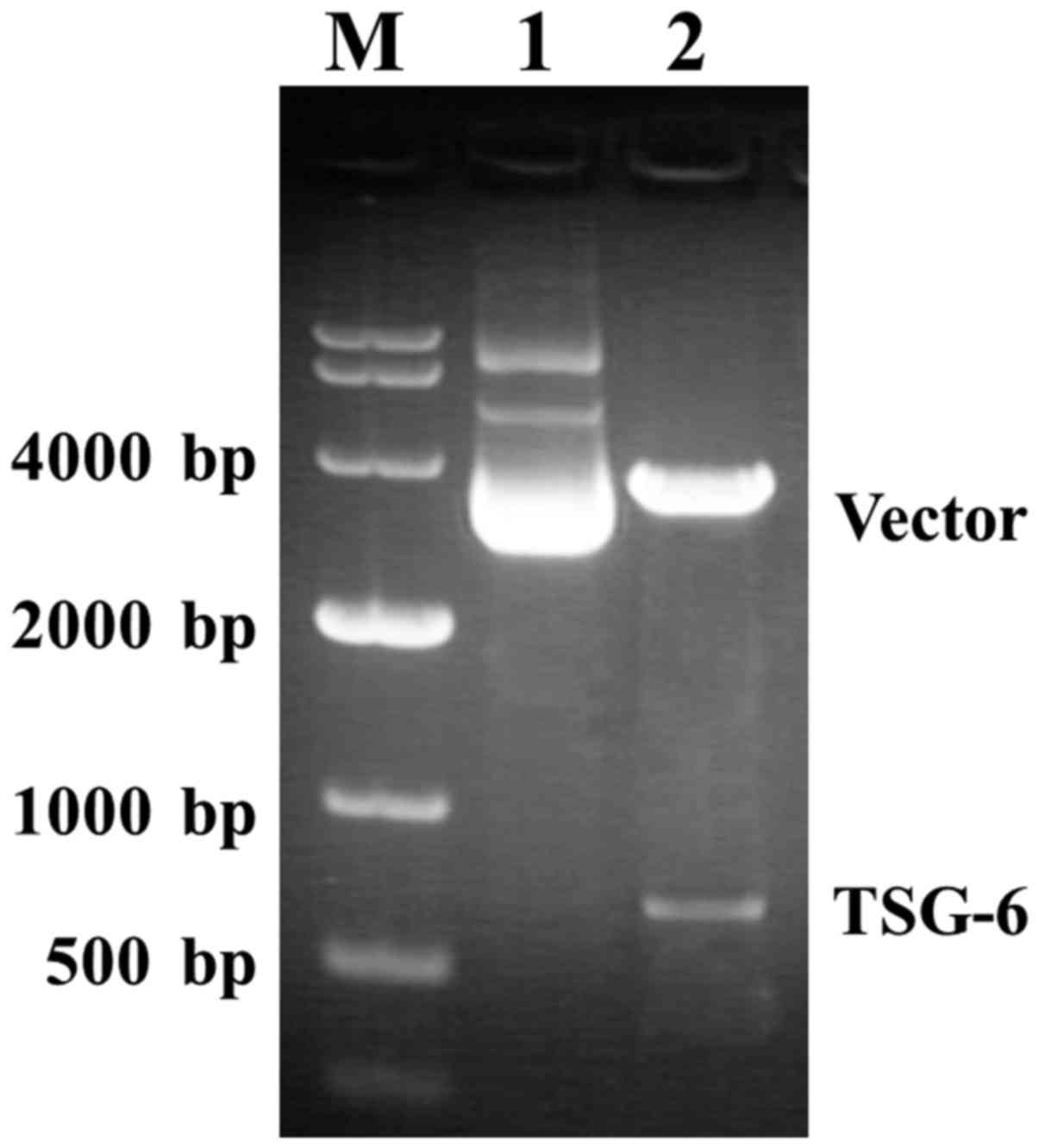

successfully cloned into the pLVX-Puro vector (Fig. 1). Agarose gel electrophoresis

revealed the positive clones after infection, with 1,179 bp and 198

bp size bands for positive and negative transformants, respectively

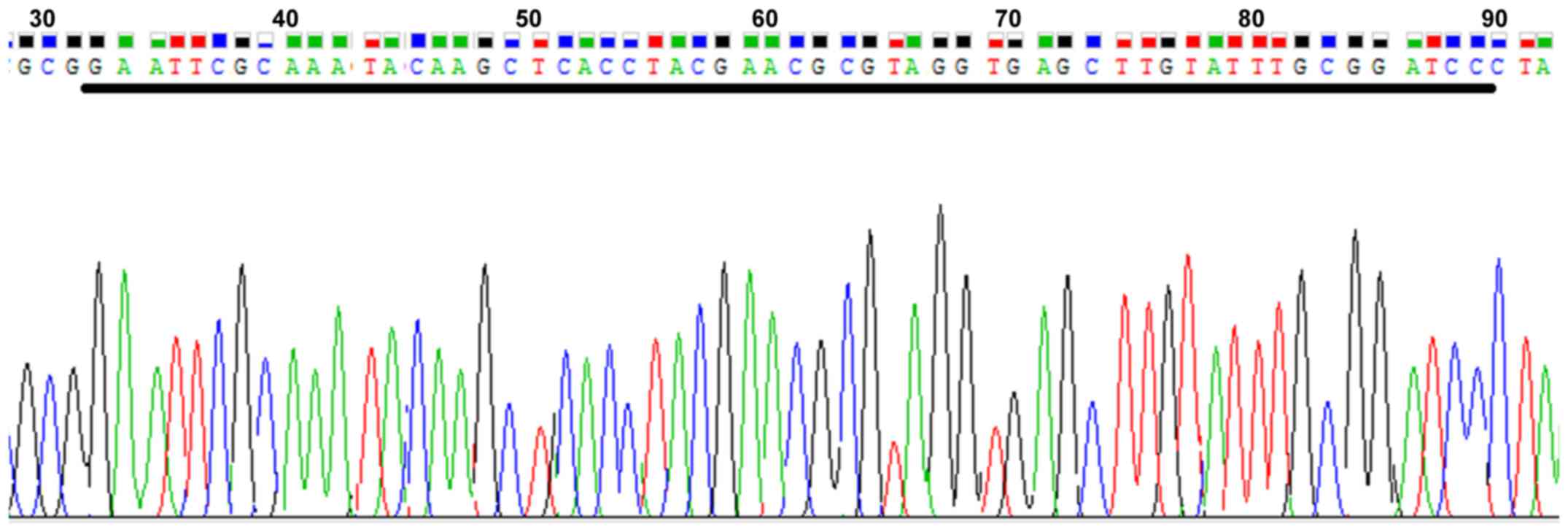

(Fig. 2). After BLAST detection,

the sequencing results of the clones revealed that the sequence

identity was 828/828 (100%) and the target gene lentiviral vector

had been successfully constructed (Fig. 3).

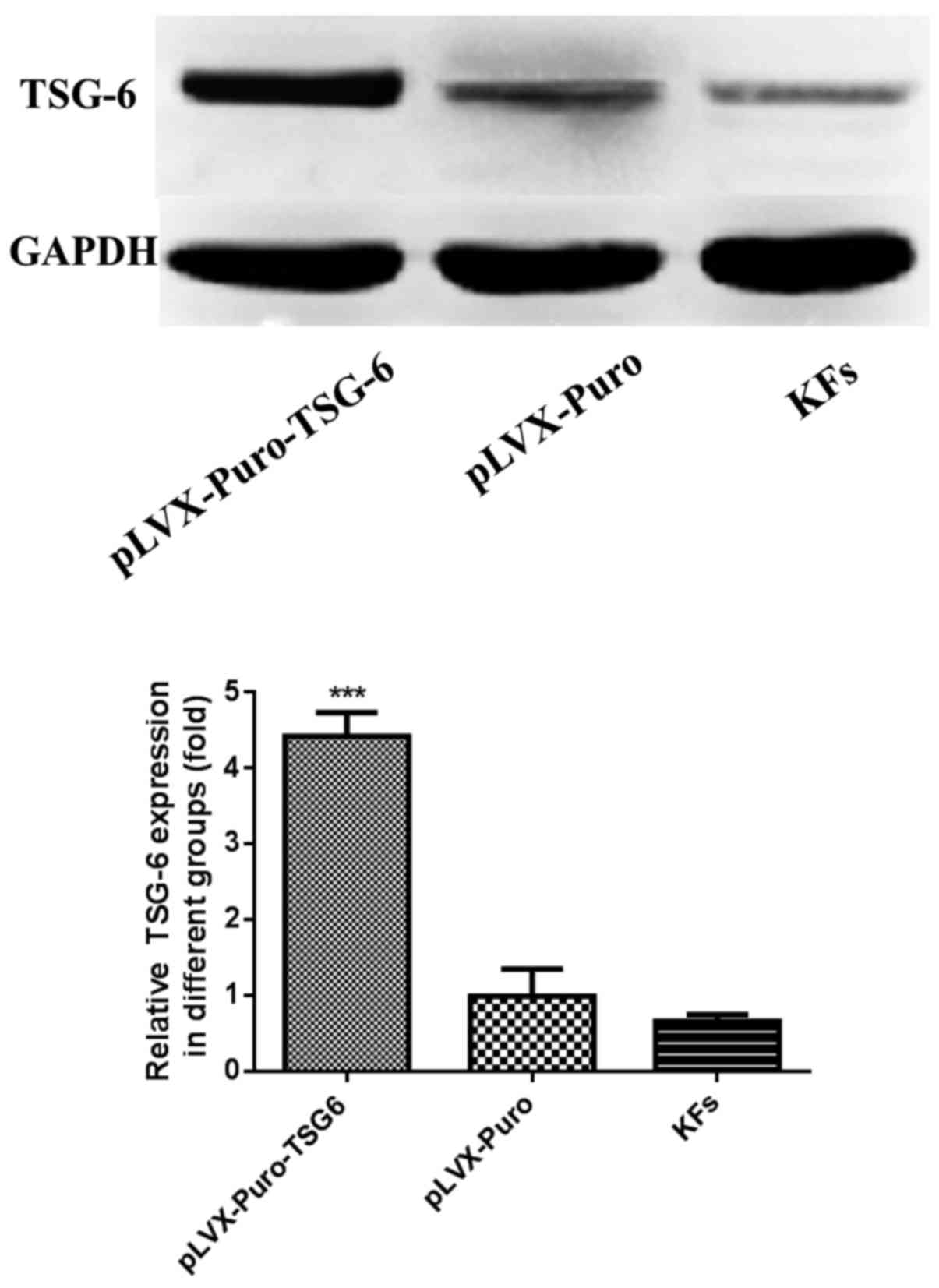

TSG-6 expression in KFs following

infection

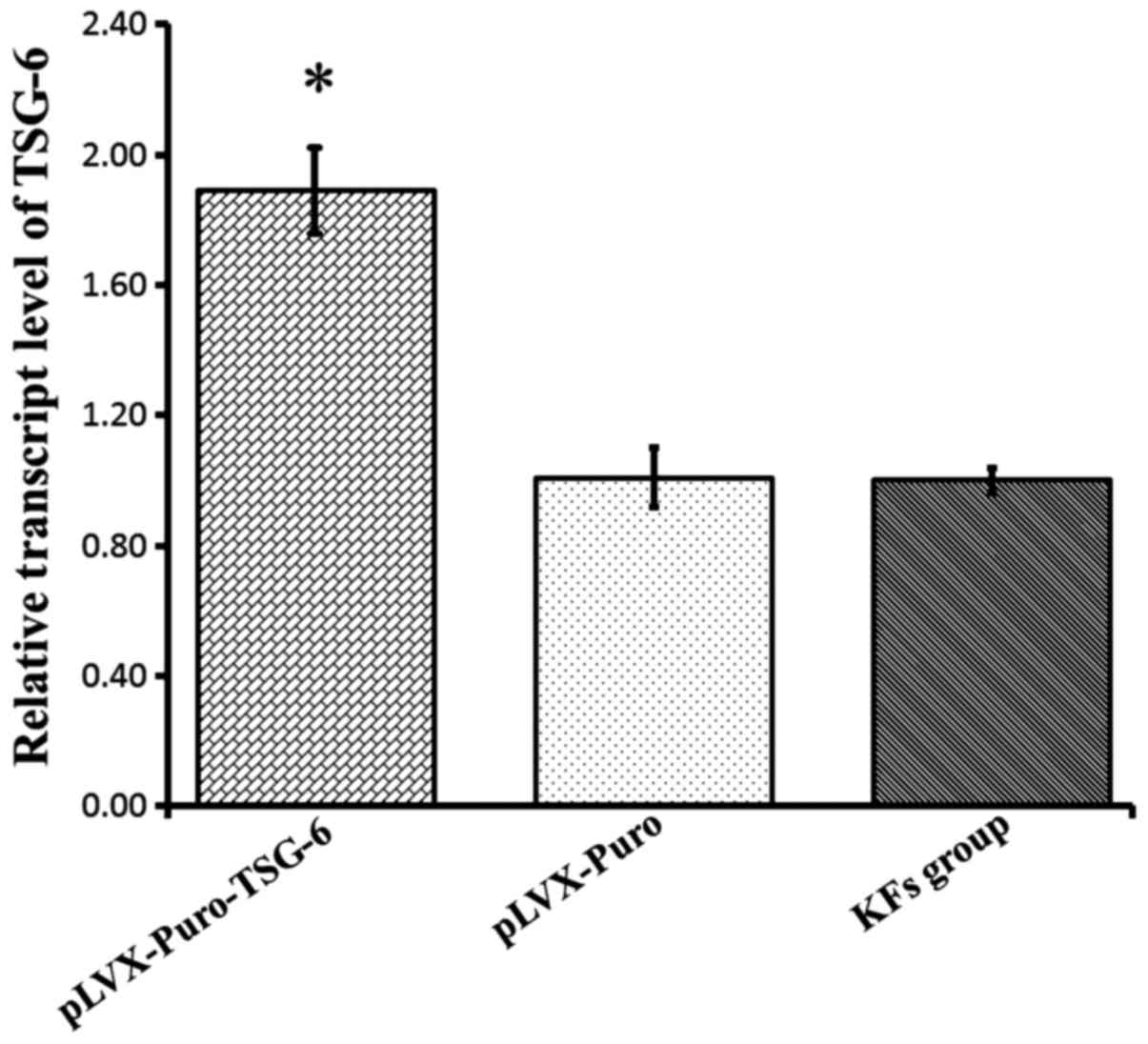

To determine the efficiency of transfection in KFs,

total RNA was extracted and RT-PCR was performed. The data

indicated that a high level of TSG-6 mRNA expression was detected

in the pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 group compared with the KF and Plvx-Puro

groups (P<0.05), while there was no significant difference

between the pLVX-Puro group and the KF group (P>0.05). This

suggested that the exogenous TSG-6 gene was transduced successfully

(Fig. 4). To further verify this

result, TSG-6 protein expression was determined using western blot

analysis. The results suggested that the expression of TSG-6

protein was increased significantly in the pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 group

compared with the pLVX-Puro group and the KF group (P<0.05),

while there was no significant difference between the pLVX-Puro

group and the KF group (P>0.05; Fig. 5).

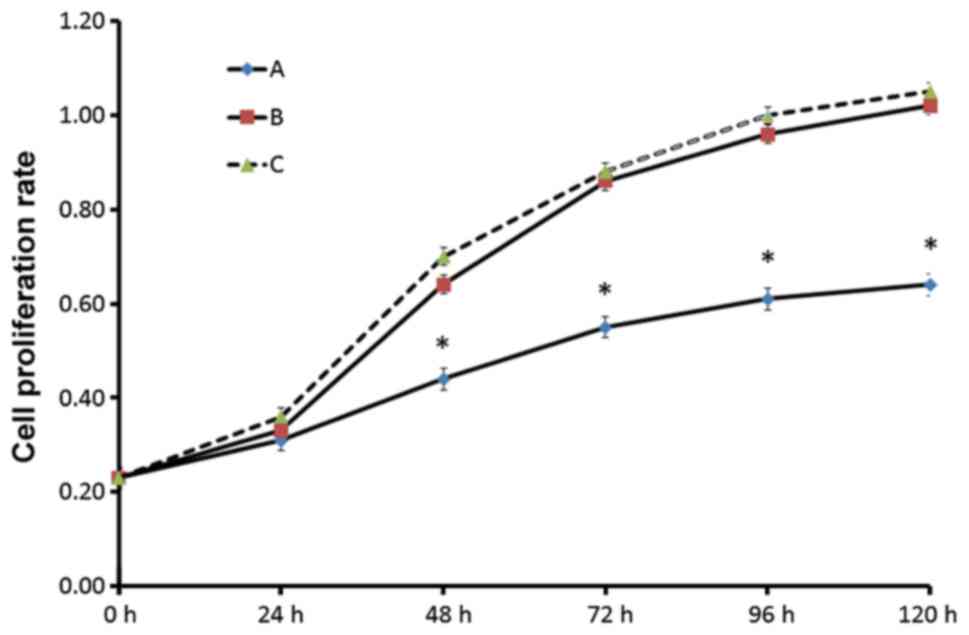

TSG-6 overexpression inhibited cell

proliferation

Cell viability was determined using an MTT assay.

Compared with the control and pLVX-Puro group, the proliferation of

the TSG-6 transfected cells was significantly decreased. However,

there was no significant difference between the pLVX-Puro group and

the KF group, which demonstrated that the vector itself had no

effect on the viability of KFs (Fig.

6).

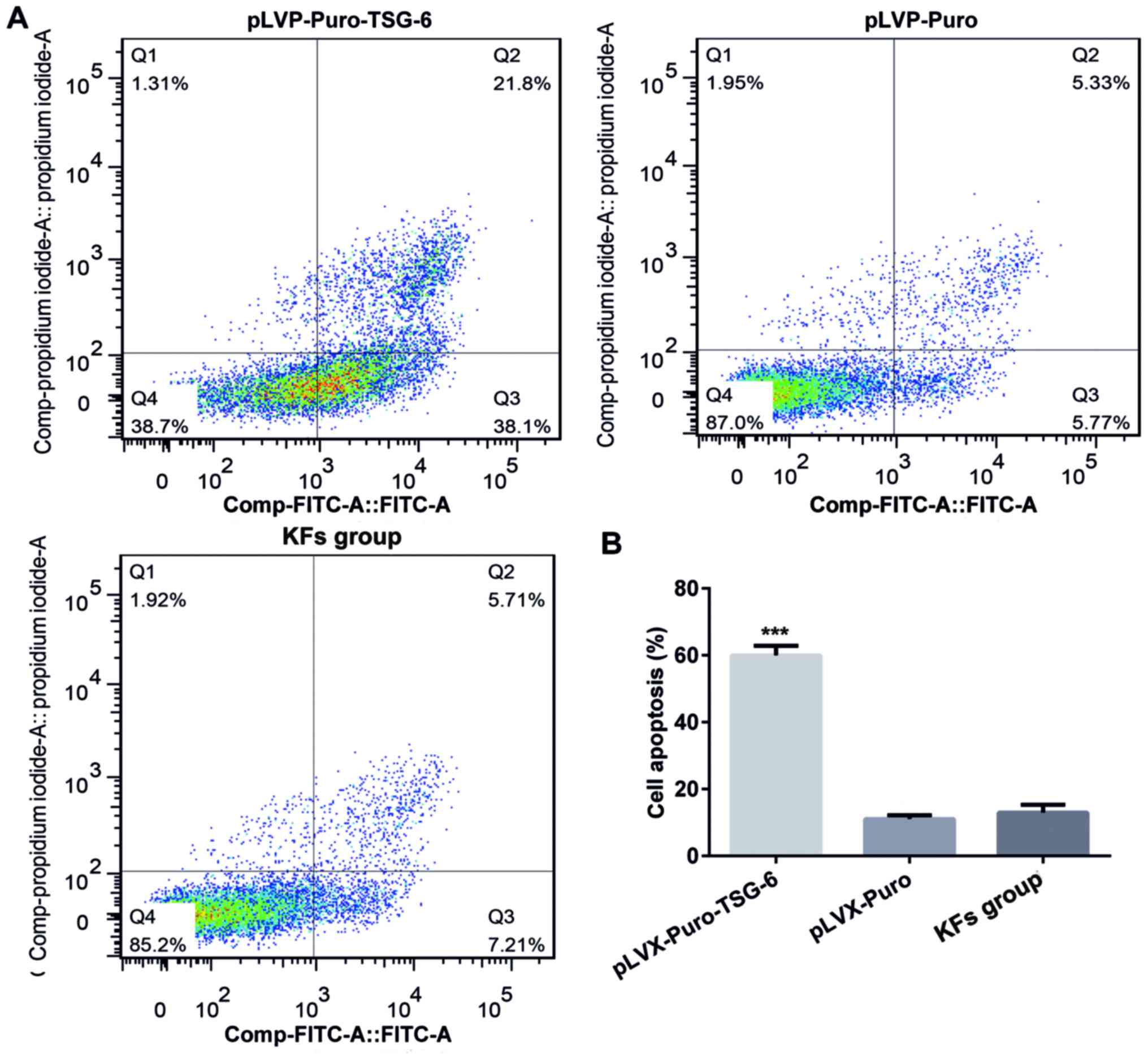

Overexpression of TSG-6 induced

apoptosis of KFs

Flow cytometry was performed to determine the rate

of cell apoptosis. Apoptosis was analyzed by double-staining with

Annexin V-FITC and PI. The apoptosis rate in the pLVX-Puro-TSG-6

group was 51.92%, which was significantly higher than that in

pLVX-Puro group (19.00%) and the KF group (3.59%; P<0.05). There

was no significant difference in apoptosis rate between the

pLVX-Puro group and the KF cell group (Fig. 7).

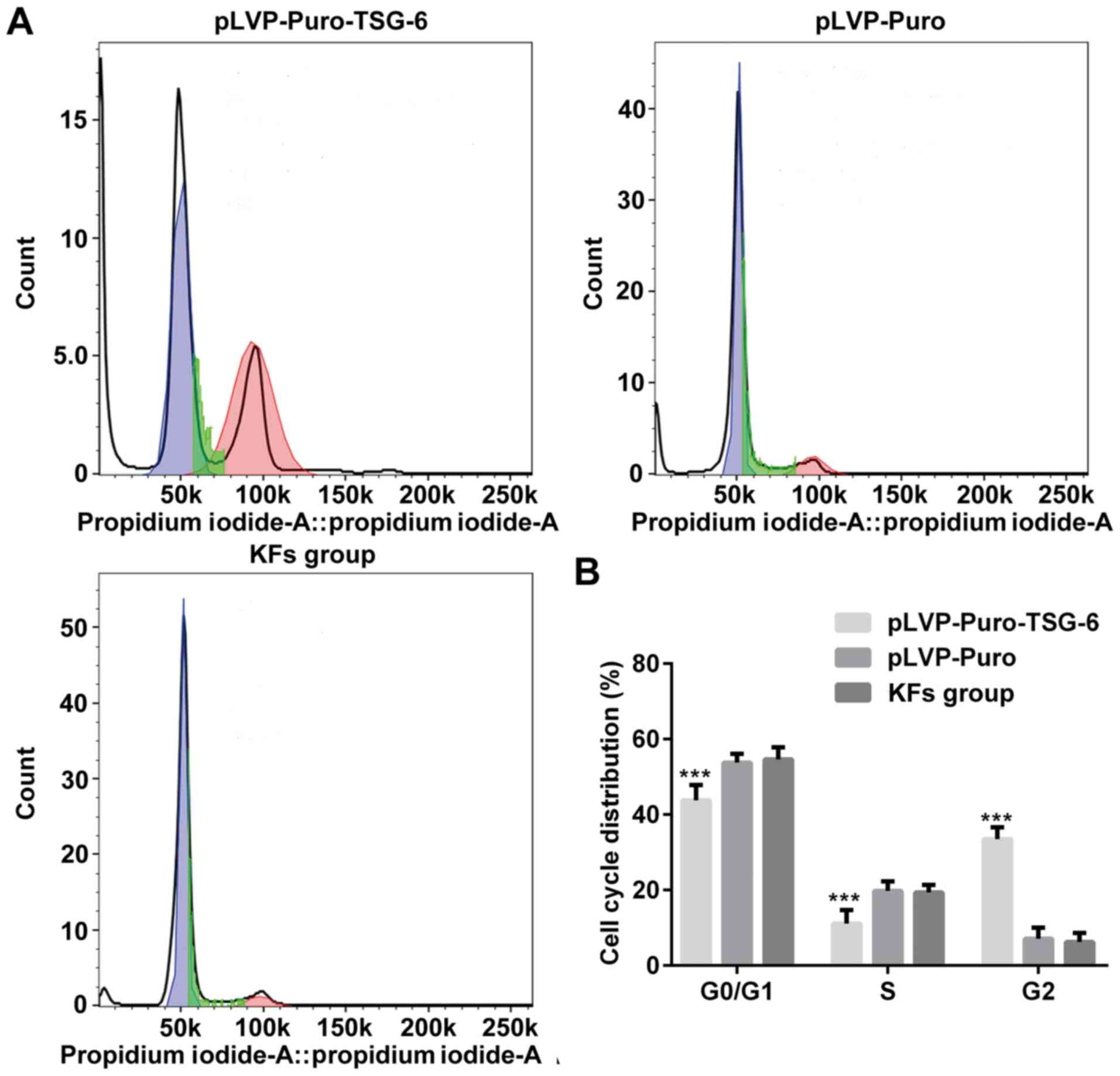

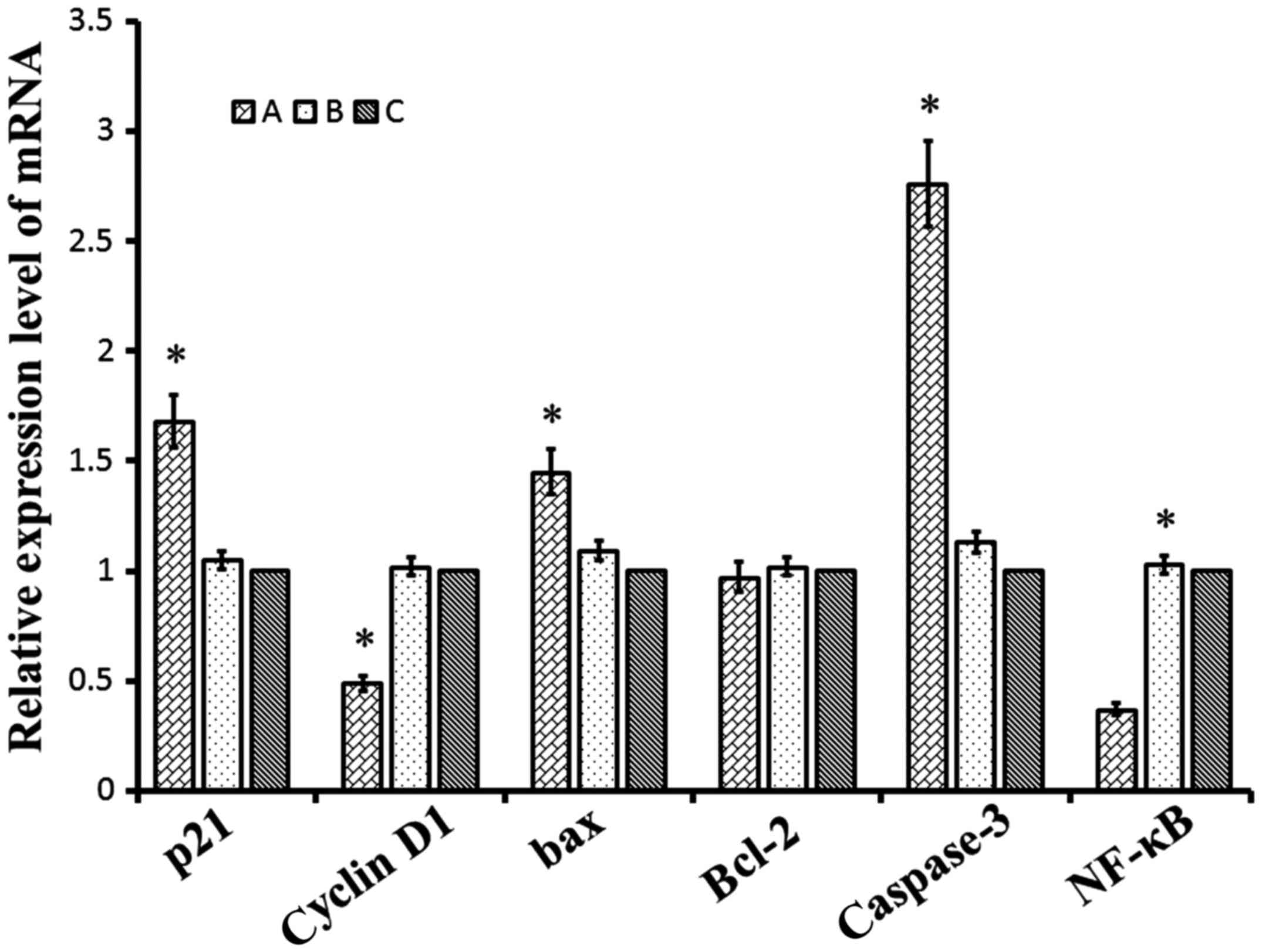

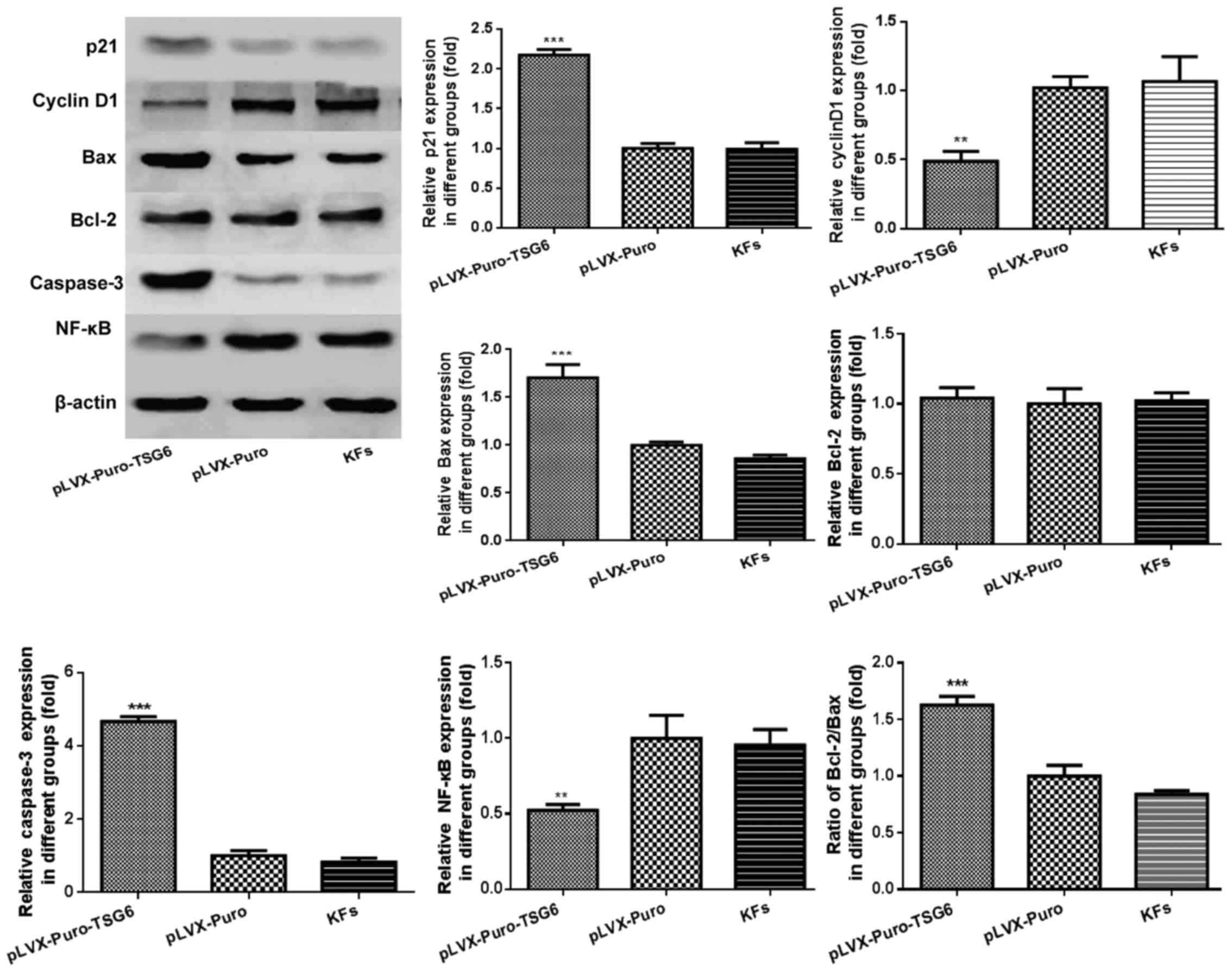

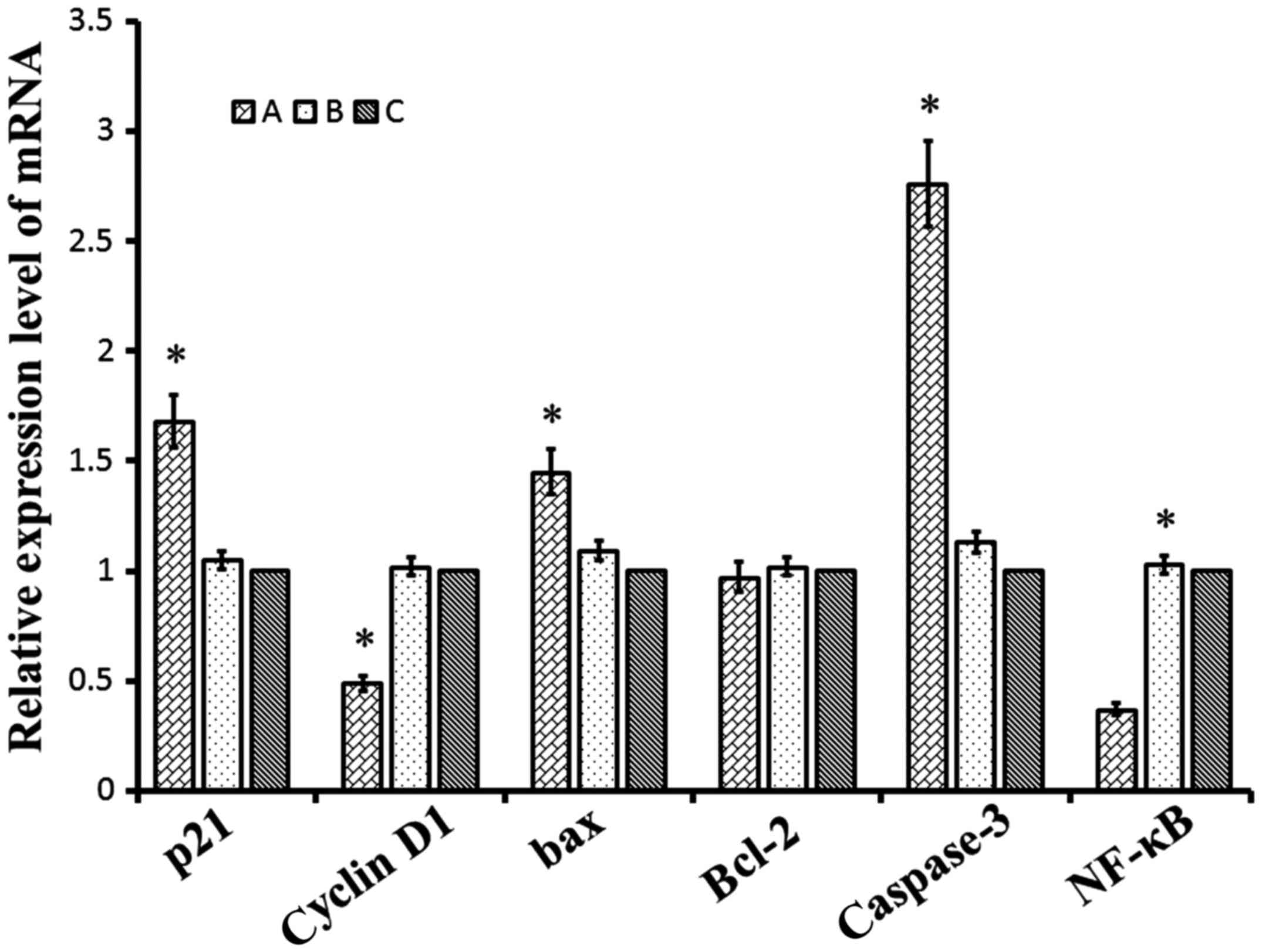

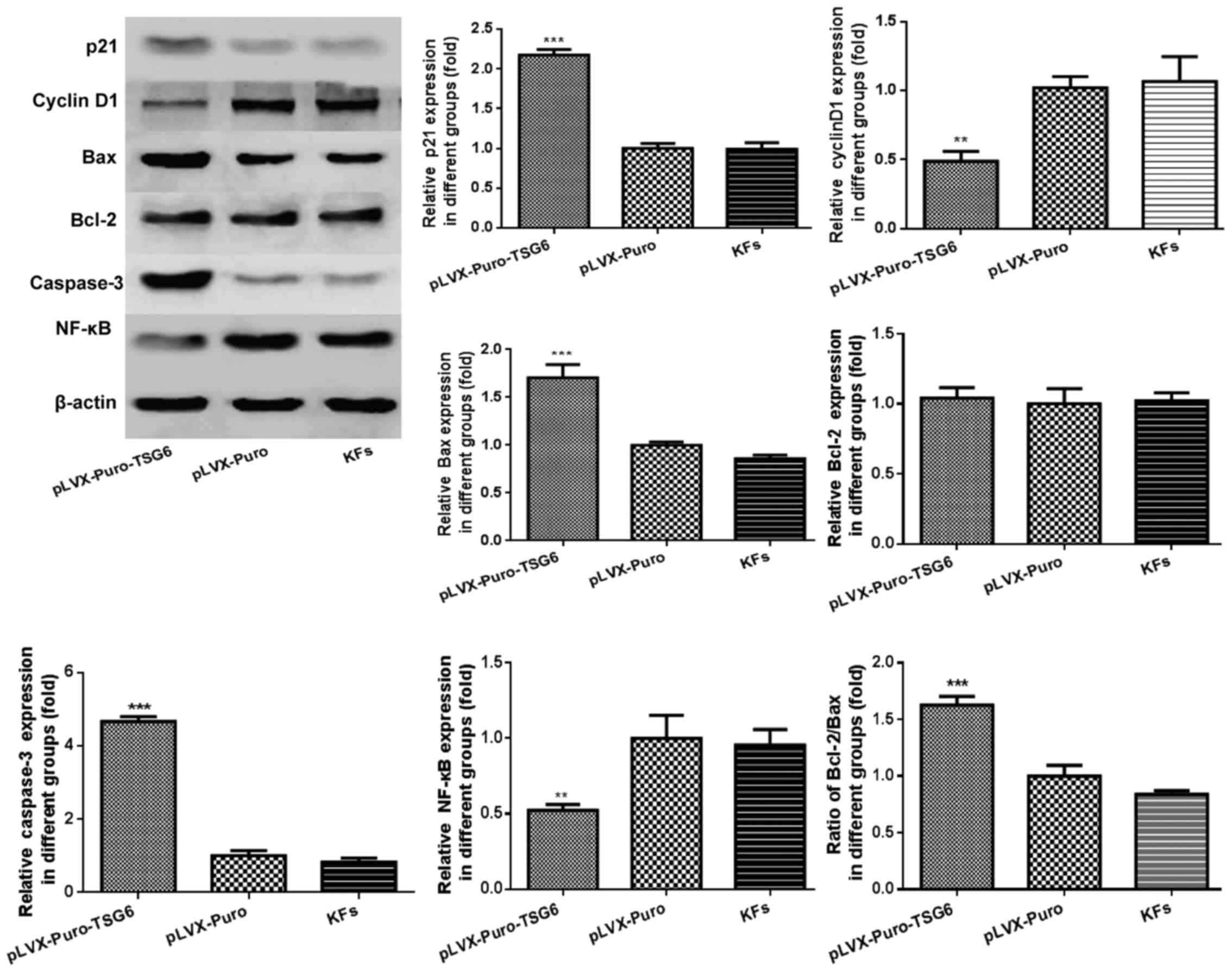

TSG-6 regulated expression of genes

and proteins involved in proliferation, cell cycle and

apoptosis

Whether the regulation of TSG-6 affects proteins

involved in proliferation, apoptosis and cell cycle in KFs was

investigated. Total cellular mRNA or protein was isolated from

cells transfected with pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 or pLVX-Puro, and

untransfected cells. Flow cytometry analysis suggested that cells

were arrested in G2/M phase by TSG-6 overexpression (Fig. 8). Levels of p21, cyclin D1, Bax,

Bcl-2, caspase-3 and NF-κB were determined by RT-PCR and western

blot. The RT-PCR results indicated that transfection of TSG-6 led

to an increase in the expression of p21, Bax and caspase-3.

Additionally, overexpression of TSG-6 decreased the mRNA levels of

cyclin D1 and NF-κB (Fig. 9). The

ratio of Bcl-2/Bax was also decreased significantly in the

TSG-6-transfected cells compared with the control group. Similar

results were confirmed by western blot; overexpressed TSG-6

markedly increased the protein levels of p21, Bax and caspase-3

(Fig. 10).

| Figure 9.Relative mRNA expression levels of

p21, cyclin D1, Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3 and NF-κB. A, pLVX-Puro-TSG-6

transfected cells; B, pLVX-Puro transfected cells; C, keloid

fibroblasts. Data were presented by mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. KFs.

TSG-6, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6; Bax, apoptosis

regulator Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2, apoptosis regulator

B-cell lymphoma-2; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB. |

| Figure 10.Protein expression of p21, cyclin D1,

Bax, Bcl-2, caspase-3 and NF-κB. Data are presented as mean ±

standard deviation. **P<0.05, ***P<0.05 vs. KFs. Bax,

apoptosis regulator Bcl-2-associated X protein; Bcl-2, apoptosis

regulator B-cell lymphoma-2; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; TSG-6, tumor

necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6; KFs, keloid fibroblasts. |

Discussion

Keloid formation occurs when the normal

wound-healing process is disordered and the evolving scar remains

in the proliferative phase of healing. The scar may grow beyond the

boundaries of the original wound (13). It has been identified that

apoptosis may be a mechanism by which granulation tissue develops,

thus decreasing cellularity and scar formation (14). The mRNA expression of TSG-6 in

keloid was previously compared with normal skin and it was

demonstrated that low expression of TSG-6 may participate in the

formation of keloid. The previous investigations indicated that the

expression level of TSG-6 in primary keloid fibroblasts derived

from individual patients was significantly higher than in normal

skin (15), which is supported by

the results and conclusions of the present study.

TSG-6 is a hyaluronic acid (HA)-binding protein

composed of a single-strand module of two α-helices and two

triple-strand β-sheets arranged around a large hydrophobic core

(16). TSG-6 is involved in the

regulation of leukocyte migration and the pattern of expression

indicates that it may be associated with extracellular matrix

remodeling (17) Increased TSG-6

protein expression has been detected in the synovial fluid of

patients with arthritis, and recombinant TSG-6 protein has been

identified to have potent anti-inflammatory effects in vivo

(18). It has been indicated that

TSG-6 is part of a cytokine-initiated feedback loop that reduces

the inflammatory response. TSG-6 was observed to form a stable,

possibly covalent, 120 kDa complex with a serine protease inhibitor

and inter-α inhibitor (IαI) (19).

Furthermore, anti-plasmin activity was significantly increased by

this complex compared with IαI alone (20). In conclusion, TSG-6 may be a key

factor involved in regulating leukocyte migration and matrix

remodeling, caused by break down of latent metalloproteinases in

the extracellular matrix via enhanced activity of plasmin.

In the current study, a lentiviral vector carrying

the TSG-6 gene was transfected into KFs, and increased the

expression of TSG-6 mRNA confirmed that the transduction was

effective. In addition, western blot results indicated that the

TSG-6 protein in the pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 group was primarily encoded by

the exogenous TSG-6 gene. To determine whether TSG-6 has selective

cytotoxic activity in KFs, MTT and apoptosis assays were performed,

and the mRNA and protein levels of key molecules were determined.

According to the MTT results, TSG-6 inhibited KF proliferation

selectively compared with the negative control. Flow cytometry

analysis suggested that TSG-6 selectively induced KF cell death and

accumulation of cells in G2/M phase by preventing KFs from entering

M phase. RT-PCR and western blot results also supported these

conclusions.

Recent studies have revealed that keloids have

tumor-like biological functions, and the roles of therapeutic

strategies such as microRNAs, bone morphogenetic proteins, activin

membrane bound inhibitor and heat shock protein 70 in keloids have

been investigated (21–23). It has been confirmed that TSG-6 is

lowly expressed in prostate cancer and can be a potential marker

for prostate cancer diagnosis (24). A previous study identified that

TSG-6 combined with Yeast Cytosine Deaminase and 5-Fluorocytosine

exerts anti-tumor effects (25).

Pathogenic mechanisms of keloid have not been elucidated in detail;

however, controlling fibroblast proliferation and apoptosis via

certain targeted genes may be an effective therapeutic strategy for

treating keloids. In the current study, TSG-6 overexpression

increased apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation, which could

offer a protective effect against keloid development.

In summary, KFs transfected with a lentiviral vector

carrying TSG-6 expressed a high level of exogenous TSG-6.

Transduction of the pLVX-Puro-TSG-6 selectively suppressed

proliferation and induced apoptosis in KFs, which confirmed the

role of TSG-6 in KFs. As a result, TSG-6 has potential as a gene

therapy candidate for the treatment of keloid, and may result in

novel and effective therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (no. 81272107).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors contributions

ZC conceived, designed, coordinated and performed

all the experiments, conducted the statistical analysis and drafted

the manuscript. XYL collected all samples and achieved particle

analysis. HW and XJL assisted in study design and manuscript

editing. All the authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The current study was approved by the institutional

review board of Anhui Medical University (Hefei, China), and

written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to

inclusion. The study was performed according to the principles of

the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gupta J, Gantyala SP, Kashyap S and Tandon

R: Diagnosis, management, and histopathological characteristics of

corneal keloid: A case series and literature review. Asia Pac J

Ophthalmol (Phila). 5:354–359. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jeon YR, Ahn HM, Choi IK, Yun CO, Rah DK,

Lew DH and Lee WJ: Hepatocyte growth factor-expressing adenovirus

upregulates matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression in keloid

fibroblasts. Int J Dermatol. 55:356–361. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Syed F, Singh S and Bayat A: Superior

effect of combination vs. single steroid therapy in keloid disease:

A comparative in vitro analysis of glucocorticoids. Wound Repair

Regen. 21:88–102. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Har-Shai Y and Zouboulis CC: Intralesional

cryotherapy for the treatment of keloid scars: A prospective study.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 136:397e–398e. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lee MJ, Kim DH, Ryu JS, Ko AY, Ko JH, Kim

MK, Wee WR, Khwarg SI and Oh JY: Topical TSG-6 administration

protects the ocular surface in two mouse models of

inflammation-related dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

56:5175–5181. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kim JA, Ko JH, Ko AY, Lee HJ, Kim MK, Wee

WR, Lee RH, Fulcher SF and Oh JY: TSG-6 protects corneal

endothelium from transcorneal cryoinjury in rabbits. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 55:4905–4912. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Baranova NS, Nilebäck E, Haller FM, Briggs

DC, Svedhem S, Day AJ and Richter RP: The inflammation-associated

protein TSG-6 cross-links hyaluronan via hyaluronan-induced TSG-6

oligomers. J Biol Chem. 286:25675–25686. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tan KT, McGrouther DA, Day AJ, Milner CM

and Bayat A: Characterization of hyaluronan and TSG-6 in skin

scarring: Differential distribution in keloid scars, normal scars

and unscarred skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 25:317–327. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mahoney DJ, Swales C, Athanasou NA,

Bombardieri M, Pitzalis C, Kliskey K, Sharif M, Day AJ, Milner CM

and Sabokbar A: TSG-6 inhibits osteoclast activity via an autocrine

mechanism and is functionally synergistic with osteoprotegerin.

Arthritis Rheum. 63:1034–1043. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kehlen A, Pachnio A, Thiele K and Langner

J: Gene expression induced by interleukin-17 in fibroblast-like

synoviocytes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Upregulation of

hyaluronan-binding protein TSG-6. Arthritis Res Ther. 5:R186–R192.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang H, Chen Z, Li XJ, Ma L and Tang YL:

Anti-inflammatory cytokine TSG-6 inhibits hypertrophic scar

formation in a rabbit ear model. Eur J Pharmacol. 751:42–49. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang GY, Yi CG, Li X, Zheng Y, Niu ZG,

Xia W, Meng Z, Meng CY and Guo SZ: Inhibition of vascular

endothelial growth factor expression in keloid fibroblasts by

vector-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor shRNA: A

therapeutic potential strategy for keloid. Arch Dermatol Res.

300:177–184. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hochman B, Isoldi FC, Furtado F and

Ferreira LM: New approach to the understanding of keloid:

Psychoneuroimmune-endocrine aspects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol.

8:67–73. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Parikh DA, Ridgway JM and Ge NN: Keloid

banding using suture ligature: A novel technique and review of

literature. Laryngoscope. 118:1960–1965. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hong X, Li X and Ning J: Expression of

TSG-6 and its significance in pathological scar. Acta Univ Med

Anhui. 48:685–687. 2013.(In Chinese).

|

|

16

|

Milner CM, Higman VA and Day AJ: TSG-6: A

pluripotent inflammatory mediator? Biochem Soc Trans. 34:446–450.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Park Y, Jowitt TA, Day AJ and Prestegard

JH: Nuclear magnetic resonance insight into the multiple

glycosaminoglycan binding modes of the link module from human

TSG-6. Biochemistry. 55:262–276. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Nagyeri G, Radacs M, Ghassemi-Nejad S,

Tryniszewska B, Olasz K, Hutas G, Gyorfy Z, Hascall VC, Glant TT

and Mikecz K: TSG-6 protein, a negative regulator of inflammatory

arthritis, forms a ternary complex with murine mast cell tryptases

and heparin. J Biol Chem. 286:23559–23569. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Baranova NS, Foulcer SJ, Briggs DC,

Tilakaratna V, Enghild JJ, Milner CM, Day AJ and Richter RP:

Inter-a-inhibitor impairs TSG-6-induced hyaluronan cross-linking. J

Biol Chem. 288:29642–29653. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang S, He H, Day AJ and Tseng SC:

Constitutive expression of inter-a-inhibitor (IaI) family proteins

and tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6) by human

amniotic membrane epithelial and stromal cells supporting formation

of the heavy chain-hyaluronan (HC-HA) complex. J Biol Chem.

287:12433–12444. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang GY, Wu LC, Liao T, Chen GC, Chen YH,

Zhao YX, Chen SY, Wang AY, Lin K, Lin DM, et al: A novel regulatory

function for miR-29a in keloid fibrogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol.

41:341–345. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lin L, Wang Y, Liu W and Huang Y: BAMBI

inhibits skin fibrosis in keloid through suppressing TGF-b1-induced

hypernomic fibroblast cell proliferation and excessive accumulation

of collagen I. Int J Clin Exp Med. 8:13227–13234. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Shin JU, Lee WJ, Tran TN, Jung I and Lee

JH: Hsp70 knockdown by siRNA decreased collagen production in

keloid fibroblasts. Yonsei Med J. 56:1619–1626. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Garcia GE, Wisniewski HG, Lucia MS,

Arevalo N, Slaga TJ, Kraft SL, Strange R and Kumar AP:

2-Methoxyestradiol inhibits prostate tumor development in

transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate: Role of tumor necrosis

factor-alpha-stimulated gene 6. Clin Cancer Res. 12:980–988. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Park JI, Cao L, Platt VM, Huang Z, Stull

RA, Dy EE, Sperinde JJ, Yokoyama JS and Szoka FC: Antitumor therapy

mediated by 5-fluorocytosine and a recombinant fusion protein

containing TSG-6 hyaluronan binding domain and yeast cytosine

deaminase. Mol Pharm. 6:801–812. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|