Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of

human mortality worldwide accounted for 32.9% of all deaths with a

steadily reaching of the number of CVD deaths from 12.1 million in

1990 to 18.6 million in 2019 (1),

and places a notable burden on human health (2,3).

At present, management of patients with CVD is challenging due to

the high mortality, disability rates and rising health care costs

(4). According to the World

Health Organization, three-quarters of CVD deaths could be

prevented through early detection and lifestyle interventions

(5). As a result, CVD has

attracted the attention of research communities and healthcare

professionals to ensure that measures, including developing the

care of cardiovascular disease in the ambulatory setting, improving

approaches to the prevention of cardiovascular disease, expanding

digital health interventions and universal health coverage

(6), have been taken.

Pharmaceutical developments and technological improvements are used

in the Western world to decrease CVD-associated mortality,

alongside interventions to control risk factors for CVD (7). Among risk factors for CVD,

pathological myocardial hypertrophy (MH) caused by long-term

overload is an independent risk factor for adverse cardiovascular

events (8). Therefore, reversing

MH may minimize the risk of cardiovascular events.

MH refers to an adaptive and compensatory change in

heart structure that maintains cardiac output during adverse

stimulation (9). The hypertrophic

process is categorized as physiological or pathological.

Physiological hypertrophy is key to preservation of normal heart

structure and function; it is a tightly regulated but reversible

phenomenon, such as the hypertrophic process that occurs in the

heart following continuous exercise (10). This is a compliant change (an

adaptive response to stimuli) in the heart and causes negligible

effects in the body. However, pathological hypertrophy is

associated with fibrosis, increased proinflammatory cytokine

production and cellular dysfunction (11). This type of maladaptive cardiac

hypertrophy, typically caused by chronically high, continuous

hemodynamic pressure, is irreversible and leads to heart failure in

severe cases (12).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (13,14), angiotensin II receptor blockers

(15,16), calcium channel antagonists,

β-receptor blockers and diuretics (17,18) are currently the primary treatments

for MH. They have all been reported to improve the clinical

symptoms of patients to a certain extent; however, the

single-target therapeutic efficacy of these agents remains

unsatisfactory as none of them significantly decrease mortality

rate (19). Therefore, MH needs

to be addressed in the CVD research. Traditional Chinese medicine

(TCM) has been reported to improve the symptoms and quality of life

of patients with heart failure (20). It has been reported that TCM

confers therapeutic benefits using natural, biologically active

ingredients that have multiple targets (21). Furthermore, agents such as

Radixastragali (Huangqi) and Ginseng (Renshen) (22,23) have gained attention due to their

stable therapeutic effects by targeting multiple targets underlying

the development of MH. Astragaloside IV(AS-IV) which is the main

component of Radixastragali, improves cardiac function and

ameliorate MH, which is mediated by attenuating inflammatory

reaction (24) and inactivating

TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1)/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (25). The pharmacological properties of

ginseng are mainly attributed to ginsenosides which plays a robust

antihypertrophic role via inhibition of NHE-1-dependent calcineurin

activation (26) and the

suppression of MCT-activated calcineurin and ERK signaling pathways

(27).

Based on clinical experience and systematic theory,

advances have been achieved in the research of TCM formulas,

extracts and compounds (28). For

example, research and development of ‘compound Danshen dropping

pill’ has contributed to treatment of coronary heart disease and

angina pectoris (29). Numerous

compounds isolated from TCM products have important properties,

such as the antimalarial effects of artemisinin (30) and the anti-inflammatory properties

of licorice extract, which contains 3 triterpenes and 13 flavonoids

(31). Furthermore, the curative

effects of novel TCM compounds that exert specific pharmacological

effects may be enhanced by elucidating their mechanism individually

whilst also characterizing their target profile. Ultimately,

treatment strategies for MH may be developed using the

multi-faceted profiles of TCM compounds combined with metabolomics

and traditional pharmacological methods (32).

Puerarin (PU) is an isoflavone chemical component

(33) found within the

Pueraria genera of plants (34). PU has been reported to exert

numerous therapeutic effects, including anti-cancer, vasodilatory

and heart protective effects (35). Furthermore, it has been previously

reported that PU ameliorates pressure overload-induced MH in

ovariectomized rats via activation of the peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-α/peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ-1 signaling pathway and regulation of energy metabolism

remodeling (36). However, the

multi-target characteristics of TCM monomers suggest that PU has

multiple therapeutic targets (37). Numerous signaling pathways are

associated with the pathophysiology of MH, including the

5′AMP-activated protein kinase/mTOR (38), PI3K/AKT/mTOR (39) and insulin-like growth factor

1/PI3K/AKT (40) signaling

pathways. Therefore, the exploration of the mechanism of PU on MH

to achieve the effect of precise treatment is urgent. Numerous

studies have reported that the Wnt signaling pathway, which is

activated in early embryonic development to promote cardiac

development and silenced in adulthood to maintain normal cardiac

function, serves an important role in CVD (41,42). As experimental data on the effects

of PU on the Wnt signaling pathway in the context of MH remain

incomplete, the present study was preformed to address this.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

PU (purity, 99.00%) was purchased from TargetMol

Chemicals, Inc. Isoproterenol hydrochloride (ISO), Dickkopf-1

(DKK1) and IM-12 were purchased from MedChemExpress. Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was purchased from Dojindo Molecular

Technologies, Inc. PVDF membranes, RIPA buffer, Actin-Tracker Green

(microfilament green fluorescent probe), DAPI Staining Solution and

BCA Protein Assay kit were purchased from Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology. TransScript® Green Two-Step qRT-PCR

SuperMix kit was purchased from TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.

Antibodies against low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

6 (LRP6; cat. no. 3395), phosphorylated (p-)p65 (cat. no. 3033),

NF-κB p65 (cat. no. C22B4), Tubulin (cat. no. 2128S), β-catenin

(cat. no. 8480), Wnt5a/b (cat. no. 2530), c-Myc (cat. no. 5605),

glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β; cat. no. 12456) and p-GSK3β

(cat. no. 9322) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP; cat. no. ab189921) and brain

natriuretic peptide (BNP, cat. no. ab236101) were purchased from

Abcam. GAPDH (cat. no. BM1623) and the secondary antibodies

including HRP Conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (cat. No.

BA1054) and HRP Conjugated AffiniPure Mouse Anti-Human IgG (cat.

No. BM2002) was from Boster.

Cells

The human cardiomyocyte AC16 cell line (MingzhouBio

Inc., cat. no. MZ-4038) was used. Cells were cultured in culture

flasks with DMEM (BasalMedia Inc.) at 37°C under 5% CO2

in a humidified atmosphere. When cells reached the logarithmic

growth phase, they were evenly distributed into six-well plates.

Experimental treatments were performed after 24 h.

In vitro cardiac hypertrophy model and

drug treatment

Cells were randomly divided as follows: i) Control,

cells treated with DMEM; ii) ISO, cells treated with 10 µM ISO for

24 h; iii) PU, cells treated with 40 µM PU for 6 h followed by 10

µM ISO for 24 h; iv) DKK1, cells treated with 780 nM DKK1 for 6 h

followed by 10 µM ISO for 24 h; v) IM12, cells treated with 30 nM

IM-12 for 24 h; vi) PU + IM12, cells treated with 40 µM PU for 6 h

followed by 30 nM IM-12 for 24 h and vi) PU + ISO + IM12, cells

treated with 40 µM PU for 6 h followed by 10 µM ISO for 24 h and 30

nM IM-12 for 6 h. A total of 1.5×105 cells were plated

in culture flasks with DMEM at 37°C under 5% CO2 in a

humidified atmosphere. The cells were washed three times with PBS

before addition of new drugs to avoid mixing of different drug

components.

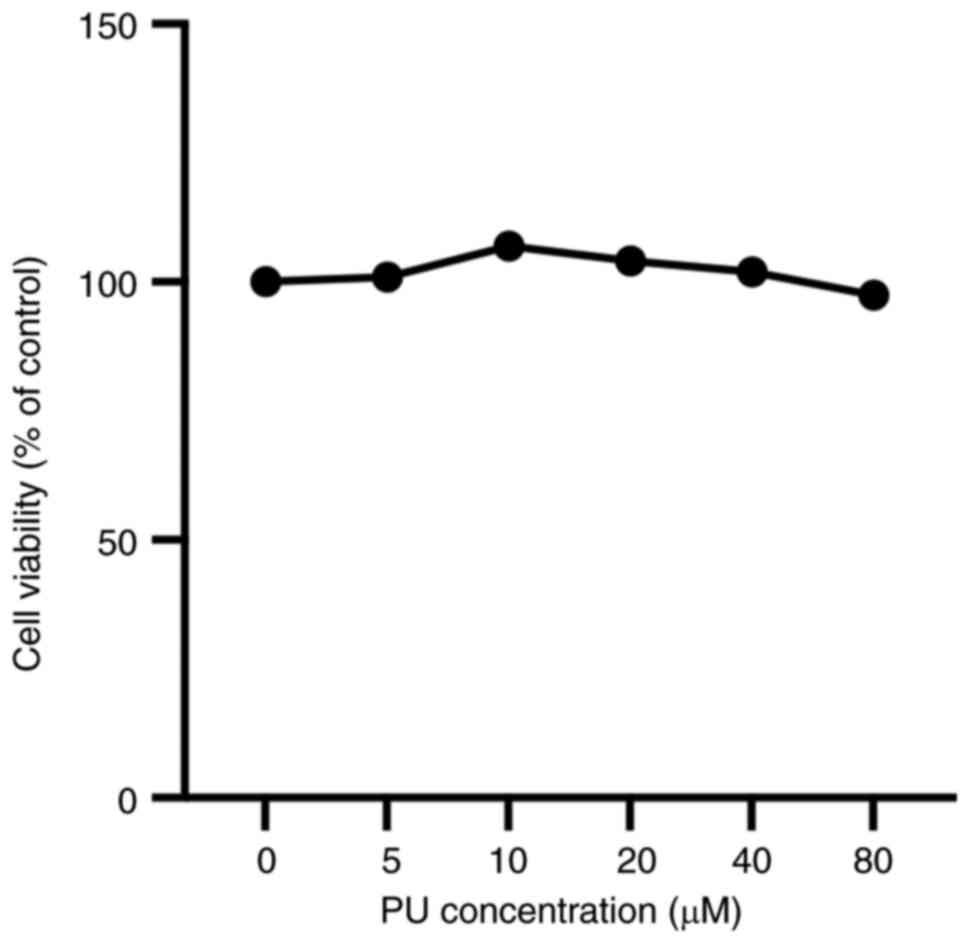

CCK-8 assay

PU was dissolved in DMSO and DMEM to produce a range

of concentrations (5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 µM) for subsequent use. The

final DMSO content was 0.2%. Cells were evenly dispersed into six

groups containing different concentrations of PU (0, 5, 10, 20, 40

and 80 µM) and inoculated into a 96-well plate (~5,000 cells/well).

PU incubation was performed for 6 h at 37°C under 5% CO2

before 100 µl CCK-8 reagent was added, followed by incubation for 2

h at 37°C under 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. The

96-well plate was assessed using a PT-3502PC microplate reader

(Beijing Potenov Technology Co. Ltd.) to quantify the absorption

value of each well at 450 nm. A line chart was constructed plotting

optical density (OD) values against drug concentrations to assess

the effect of PU on cell viability.

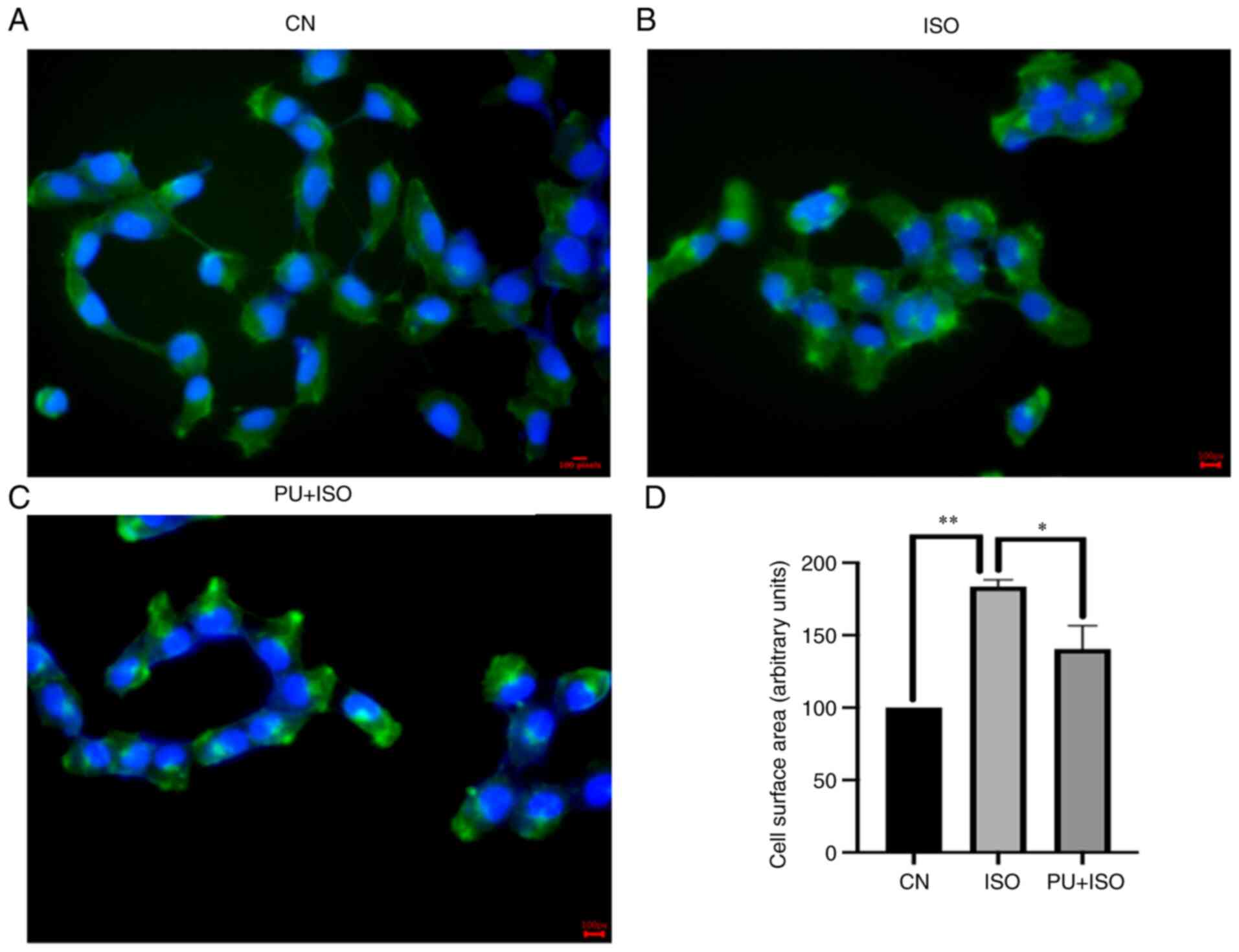

Cytoskeletal staining

The surface area of AC16 cardiomyocytes in the

different treatment groups was assessed using cytoskeletal

staining. Control, ISO and PU), cells were washed with PBS twice

and fixed using 3.7% formaldehyde solution at room temperature for

10 min in the dark according to the manufacturer's protocol for the

Actin-Tracker Green. PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 was added to

permeabilize the fixed cells for 10 min at room temperature. The

cells were stained with Actin-Tracker Green working solution

diluted with PBS containing 1–5% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 at a

ratio of 1:50 for 30 min at room temperature. Following rinsing

with PBS, 5 mg/ml DAPI (sufficient to cover each section) was added

to each well for 3–5 min at room temperature before imaging using a

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The magnification

was 400×. A total of five non-overlapping fields located at the

upper and lower left and right and center of each well was

selected. The cells in each field were numbered and sampled by a

random number generator. A total of four cells was randomly

extracted from each field. Finally, the size of cells was

quantified using ImageJ2 (version 1.53; National Institutes of

Health). The mean area of the selected cells was determined for

each well and normalized to the control.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

RNA was extracted from AC16 cells (Control, ISO and

PU) using TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

concentration of RNA was detected using a NanoDrop®

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Complementary

DNA synthesis, using incubation at 42°C for 15 min and heating at

85°C for 5 sec, was performed according to the manufacturer's

protocols of the TransScript® Green Two-Step qRT-PCR

SuperMix kit. The primer sequences were as follows: ANP forward

(F), 5′-CAACGCAGACCTGATGGATTT-3′ and reverse (R),

5′-AGCCCCCGCTTCTTCATTC-3′; BNP F, 5′-TGGAAACGTCCGGGTTACAG-3′ and R,

5′-CTGATCCGGTCCATCTTCCT-3′; β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) F,

5′-TCACCAACAACCCCTACGATT-3′ and R, 5′-CTCCTCAGCGTCATCAATGGA-3′ and

GAPDH F, 5′-CTGGGCTACACTGAGCACC-3′ and R,

5′-AAGTGGTCGTTGAGGGCAATG-3′. The reaction systems of each primer

sequence were added into a 96-well fluorescent qPCR plate and CFX

Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as follows: 94°C initial

denaturation for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 5 sec at 94°C and

30 sec at 60°C. The 2−ΔΔCq method (43) was used to assess mRNA expression

levels.

Western blotting

The cells in each group (Control, ISO, PU, DKK1,

IM12, PU + IM12, PU + ISO + IM12) were digested with 0.25% trypsin

for 25 sec at 37°C under 5% CO2 in a humidified

atmosphere, washed with PBS three times and lysed with RIPA lysis

buffer containing protease and phosphate inhibitors at 4°C for 30

min. The supernatant was collected following centrifugation (12,000

× g at 4°C for 10 min), before protein concentration was quantified

via BCA assay. An equal amount of protein (15 µg protein/lane) was

separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. PVDF

membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder solution at room

temperature for 1 h before being incubated at 4°C overnight with

specific primary antibodies. The antibodies were as follows: LRP6

(1:1,000), p-p65 (1:1,000), p65 (1:1,000), Tubulin (1:10,000),

β-catenin (1:1,000), Wnt5a/b (1:1,000), GAPDH (1:5,000), c-Myc

(1:1,000), GSK3β (1:1,000), p-GSK3β (1:1,000), ANP (1:1,000) and

BNP (1:1,000). After washing with TBST (0.1% Tween-20), membranes

were incubated with anti-rabbit (1:5,000) and anti-mouse secondary

antibodies (1:5,000) at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes

were rinsed again and treated with BeyoECL Moon (cat. no. P0018FS,

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) before bands were visualized

using the Tanon-4600 Chemiluminescence Imaging System. Finally,

blots were analyzed using ImageJ2 (version 1.53; National

Institutes of Health) to semi-quantify the protein expression

levels.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using

GraphPad Prism (version, 9.1.1; GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Comparisons between groups were performed using one-way ANOVA with

Dunnett's (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7) or Tukey's post hoc test

(Fig. 8). Data are presented as

the mean ± SEM of ≥3 independent experimental repeats. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

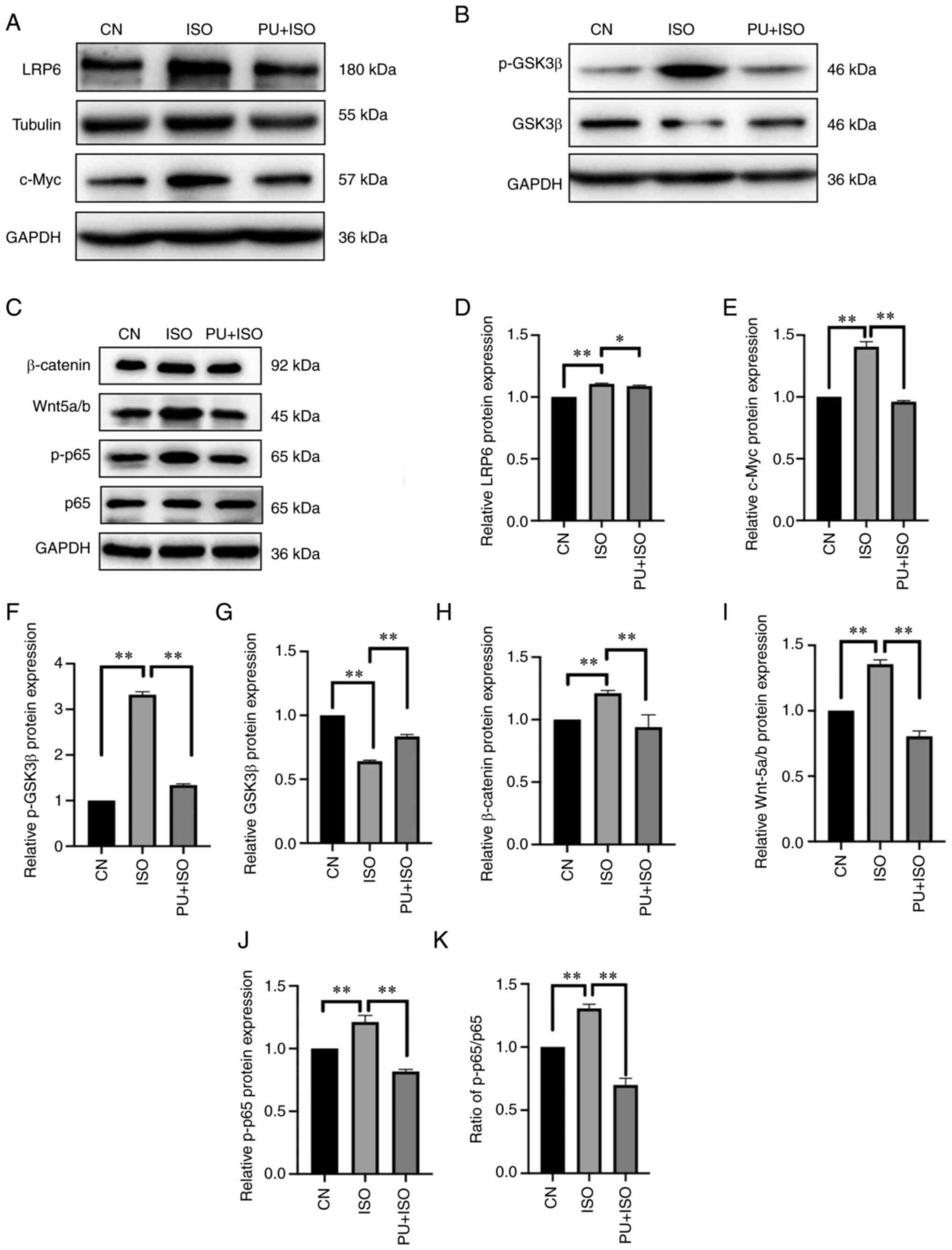

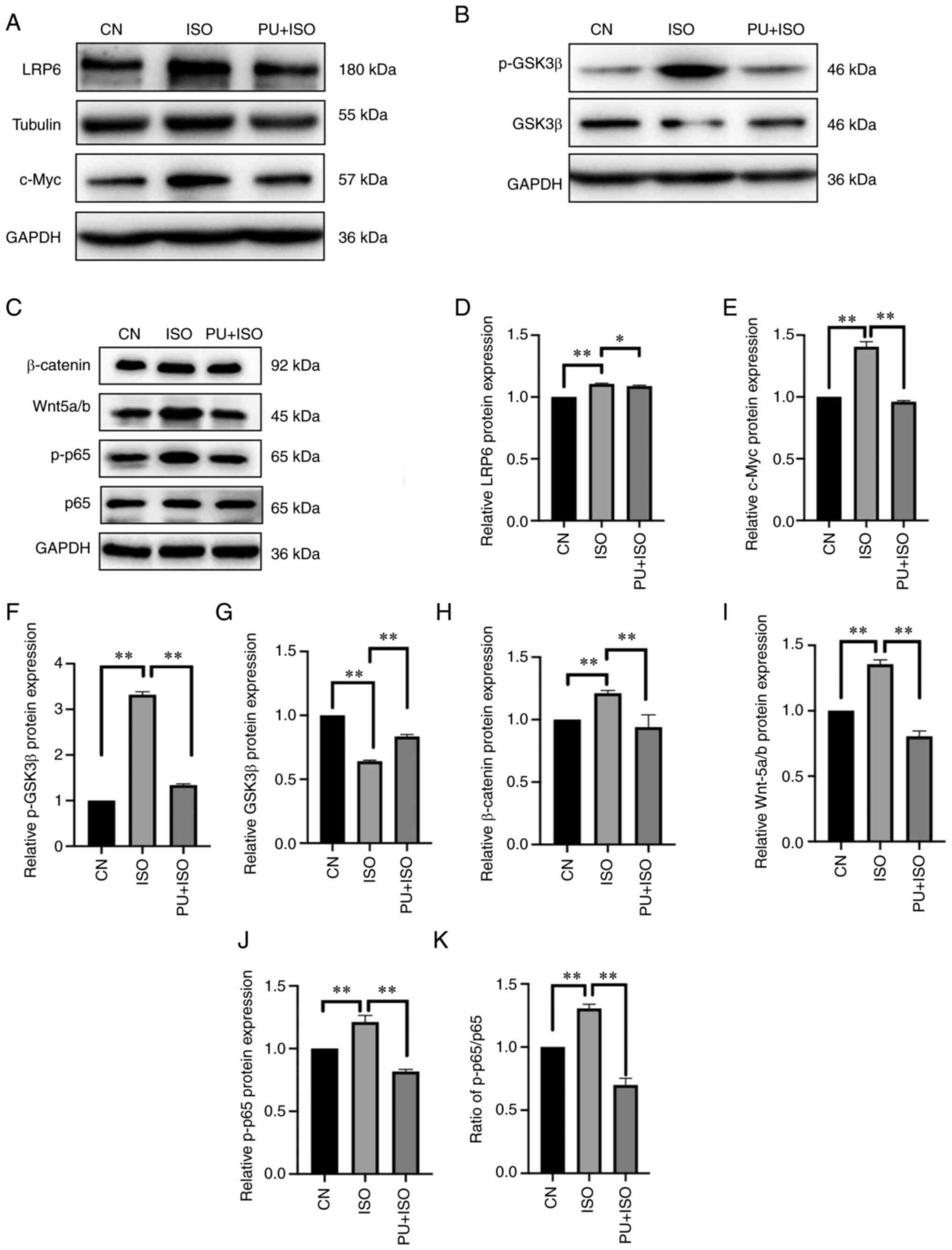

| Figure 5.Effect of PU on expression of

components in the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways. (A)

Representative western blotting images of LRP6, c-Myc, p-GSK3β and

GSK3β. (B) Representative western blotting images of p-GSK3β and

GSK3β. (C) Representative western blotting images of β-catenin,

Wnt5a/b, p-p65 and p65. (D) LRP6, (E) c-Myc, (F) p-GSK3β, (G)

GSK3β, (H) β-catenin, (I) Wnt5a/b and (J) p-p65 protein expression

levels were semi-quantified. (K) Ratio of p-p65/p-65. The blots

were analyzed using ImageJ. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. CN,

control; ISO, isoproterenol; PU, puerarin; LRP6, low-density

lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6; p-, phosphorylated; GSK3β,

glycogen synthase kinase 3β. |

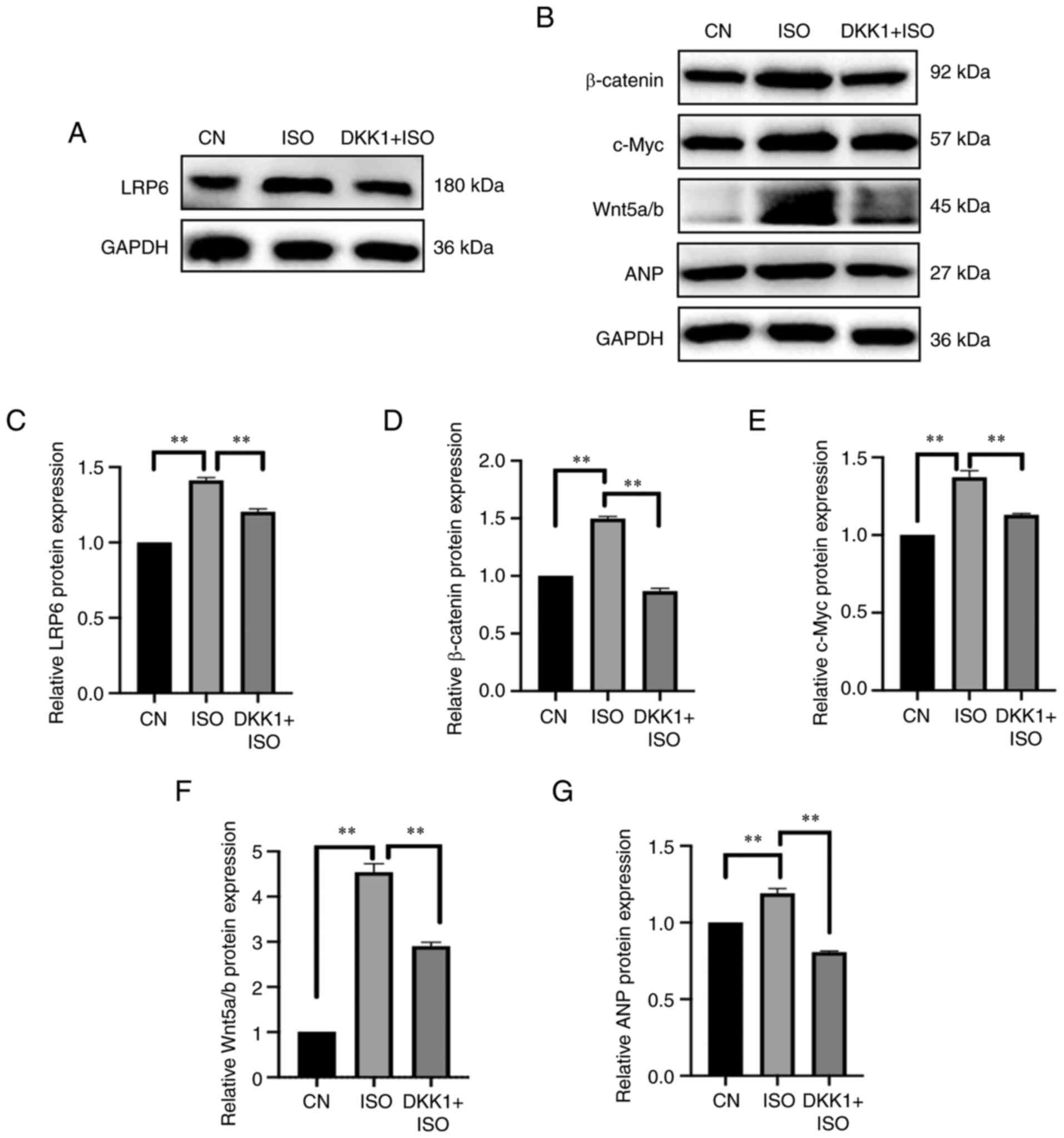

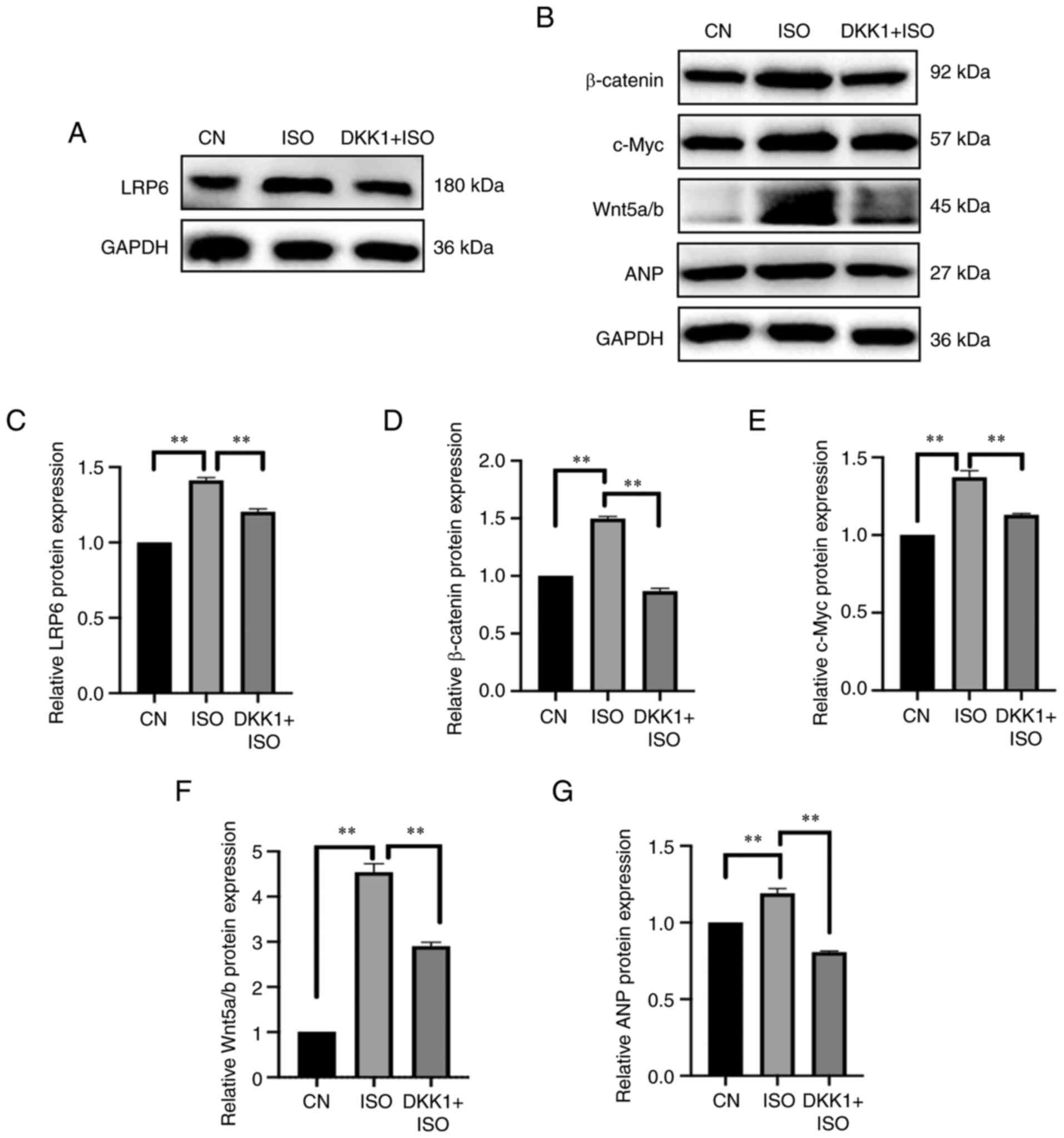

| Figure 6.Effect of DKK1 on expression of

protein in the signaling Wnt pathway. (A) Representative western

blotting images of LRP6. (B) Representative western blotting images

of β-catenin, Wnt5a/b, c-Myc and ANP. (C) LRP6, (D) β-catenin, (E)

c-Myc, (F) Wnt5a/b and (G) ANP protein expression levels were

semi-quantified. The blots were analyzed using ImageJ. **P<0.01.

DKK1, Dickkopf-1; CN, control; ISO, isoproterenol; LRP6,

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6; ANP, atrial

natriuretic peptide. |

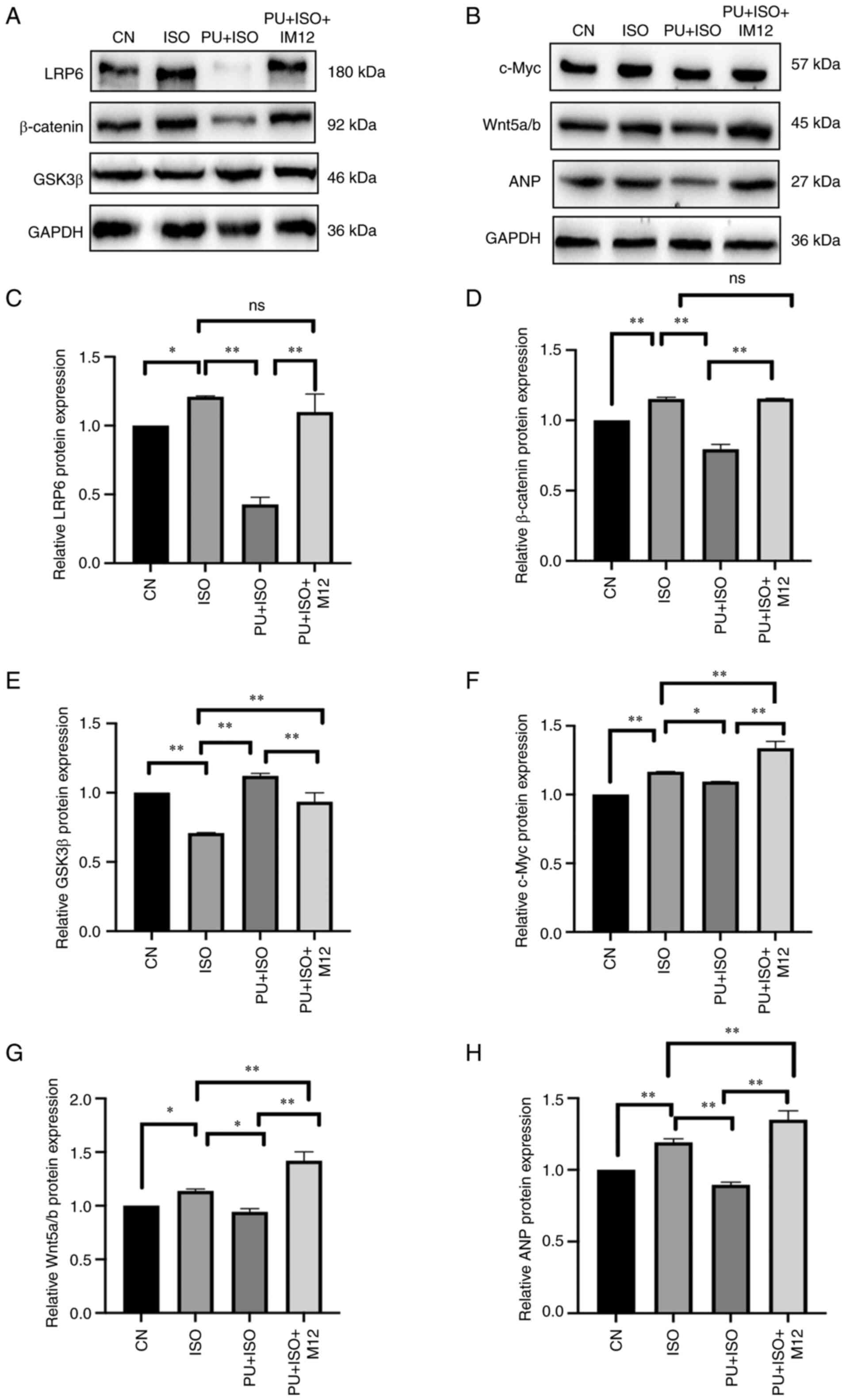

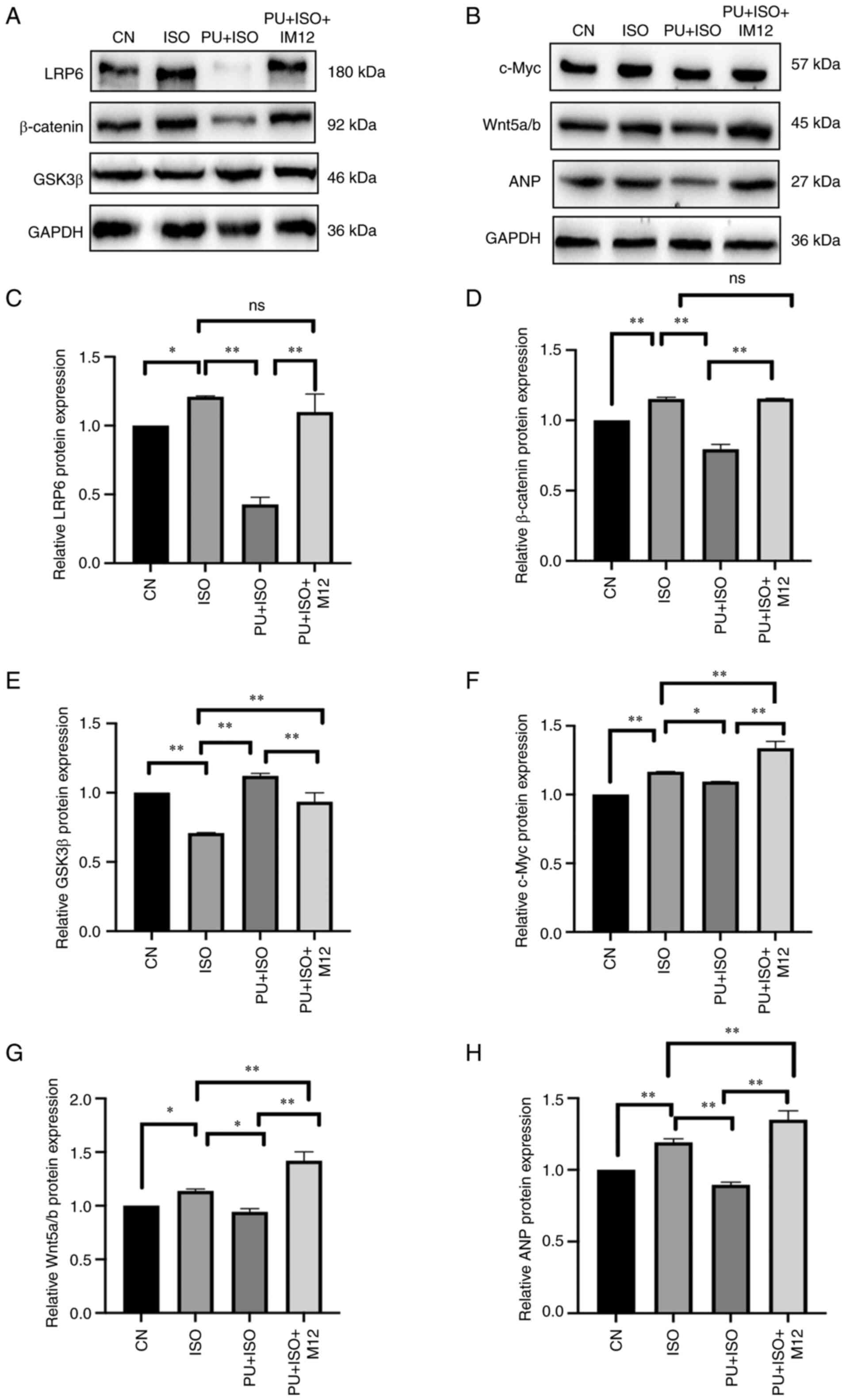

| Figure 8.Effect of ISO, PU and IM-12 on

expression of proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway. (A)

Representative western blotting images of LRP6, GSK3β and β-catenin

expression. (B) Representative western blotting images of c-Myc,

Wnt5a/b and ANP expression. (C) LRP6, (D) β-catenin, (E) GSK3β, (F)

c-Myc, (G) Wnt5a/b and (H) ANP protein expression levels were

semi-quantified. The blots were analyzed using ImageJ. *P<0.05

and **P<0.01. CN, control; ISO, isoproterenol; PU, puerarin;

LRP6, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6; GSK3β,

glycogen synthase kinase 3β; ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; ns,

not significant. |

Results

PU is not toxic to cardiomyocytes

CCK-8 assay OD values were used to assess the

effects of PU on AC16 cell viability. The results demonstrated no

significant difference in cell viability between treatment groups

(Fig. 1). These data demonstrated

that the highest concentration of PU (80 µM) had little effect on

cell viability after 6 h.

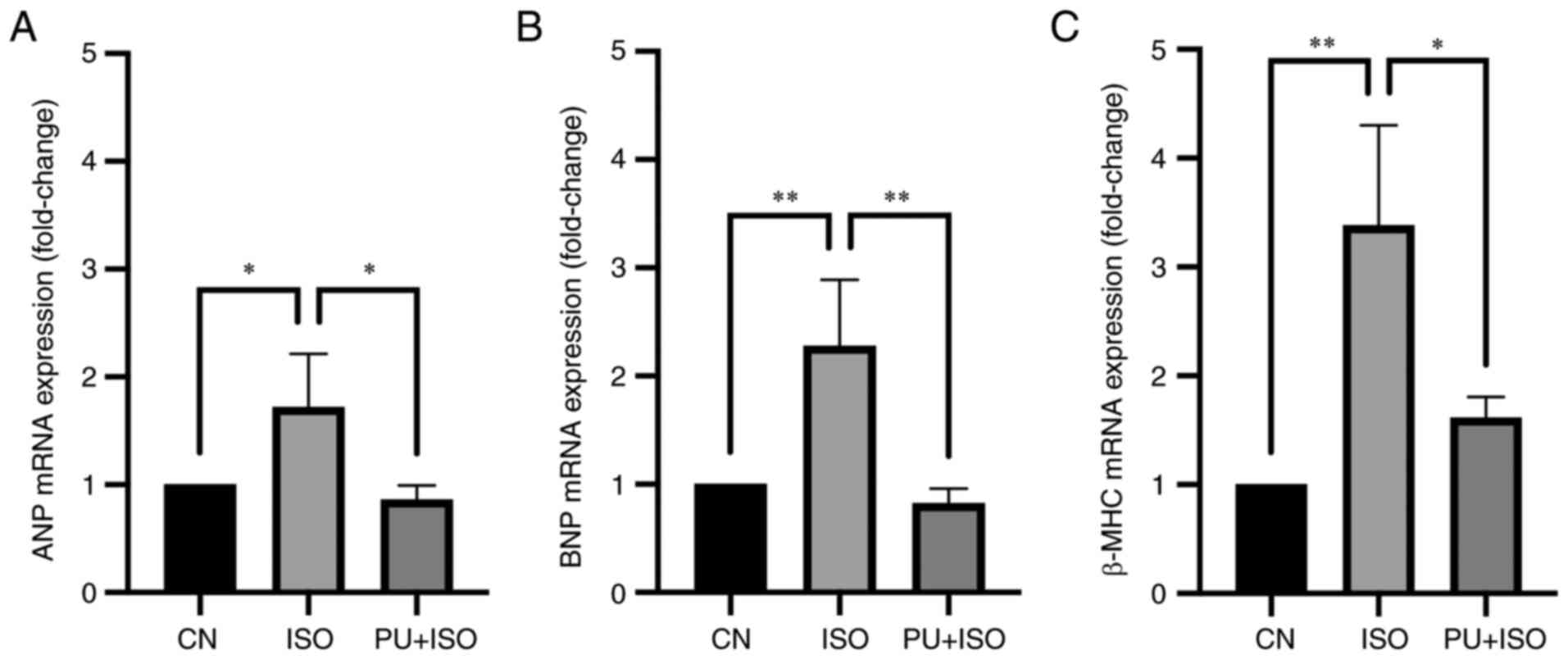

PU decreases ANP, BNP and β-MHC

transcription

The mRNA expression levels of MH markers ANP, BNP

and β-MHC were quantified using RT-qPCR. The results demonstrated

significant increases in mRNA expression levels of ANP (P<0.05;

Fig. 2A), BNP (P<0.01;

Fig. 2B) and β-MHC (P<0.01;

Fig. 2C) in the ISO group

compared with the control. By contrast, treatment with PU

significantly decreased mRNA expression levels of ANP (P<0.05),

BNP (P<0.01) and β-MHC (P<0.05) compared with the ISO group.

These results suggested that the ISO-induced MH model was

successfully established and the effect of ISO was reversed by

PU.

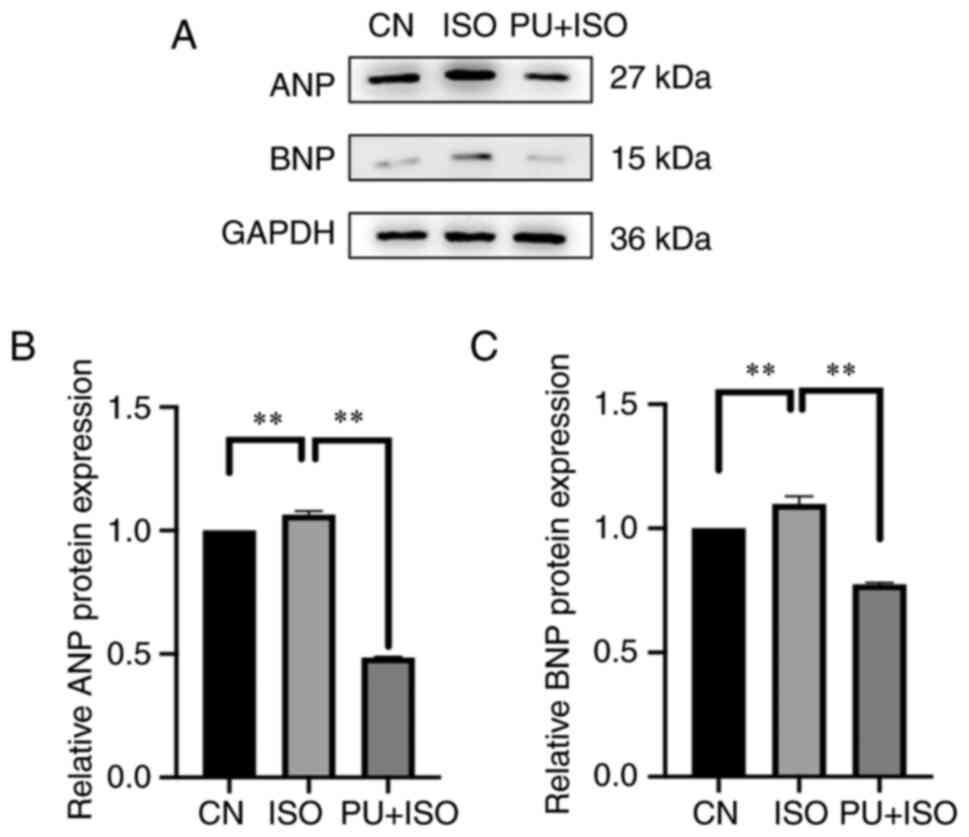

PU decreases protein expression levels

of ANP and BNP

To assess the effect of PU on ISO-induced MH,

western blotting was performed to determine protein expression

levels of ANP and BNP. Following 24 h induction with 10 µM ISO,

protein expression levels of ANP and BNP in the AC16 cardiomyocytes

were significantly higher compared with those in the control

(P<0.01; Fig. 3). However,

expression levels of ANP and BNP protein in AC16 cardiomyocytes

pretreated with PU were significantly lower compared with those in

the ISO group (P<0.01). These results demonstrated that cells

pretreated with PU were resistant to ISO-induced MH.

ISO-treated AC16 cell surface area

decreases significantly following PU pretreatment

Changes in AC16 myocardial cell area were observed

using fluorescence microscopy. The surface area of AC16 cells in

the ISO group significantly increased compared with those in the

control (P<0.01; Fig. 4A, B and

D). However, PU pretreatment significantly decreased surface

area of AC16 cells compared with those in the ISO group (P<0.05;

Fig. 4C). These results suggested

that MH was prevented by PU pretreatment.

PU inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway

To determine the potential anti-MH mechanism of PU,

core components in the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways

were assessed using western blotting. The protein expression levels

of LRP6, β-catenin, Wnt-5a/b and c-Myc and phosphorylation levels

of p65 and GSK3β, significantly increased in the ISO group compared

with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 5A-F and H-K). However, the

expression of GSK3β was significantly decreased by ISO compared

with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 5G). There was a significant

decrease in the expression of LRP6 (P<0.05), β-catenin

(P<0.01), Wnt-5a/b (P<0.01) and c-Myc (P<0.01) as well as

phosphorylation levels of p65 (P<0.01) and GSK3β (P<0.01) in

the AC16 cells pretreated with PU compared with the ISO group.

Furthermore, expression of GSK3β (P<0.01) was significantly

increased by PU pretreatment compared with the ISO group. These

results suggested that the protective effects of PU on MH may be

mediated by Wnt and NF-κB signaling pathway activity.

PU serves as an inhibitor of the Wnt

signaling pathway by antagonizing its activator

A Wnt inhibitor and activator were used to verify if

PU regulated the Wnt signaling pathway. DKK1 is an inhibitor of the

Wnt signaling pathway that has been reported to regulate embryonic

development (44). Wnt signaling

transduction is blocked by DKK1 binding, which induces LRP6

internalization (45).

After cells were pretreated with DKK1, protein

expression levels of components in the Wnt signaling pathway, such

as LRP6, β-catenin, Wnt5a/b and c-Myc, were significantly

suppressed compared with ISO group (P<0.01; Fig. 6A-G); this effect was similar to

the aforementioned effect mediated by PU. Furthermore, expression

of ANP, a cardiac hypertrophy marker, was significantly decreased

by DKK1 pretreatment (P<0.01; Fig.

6G), which suggested that inhibition of the Wnt signaling

pathway may be beneficial for the treatment of MH.

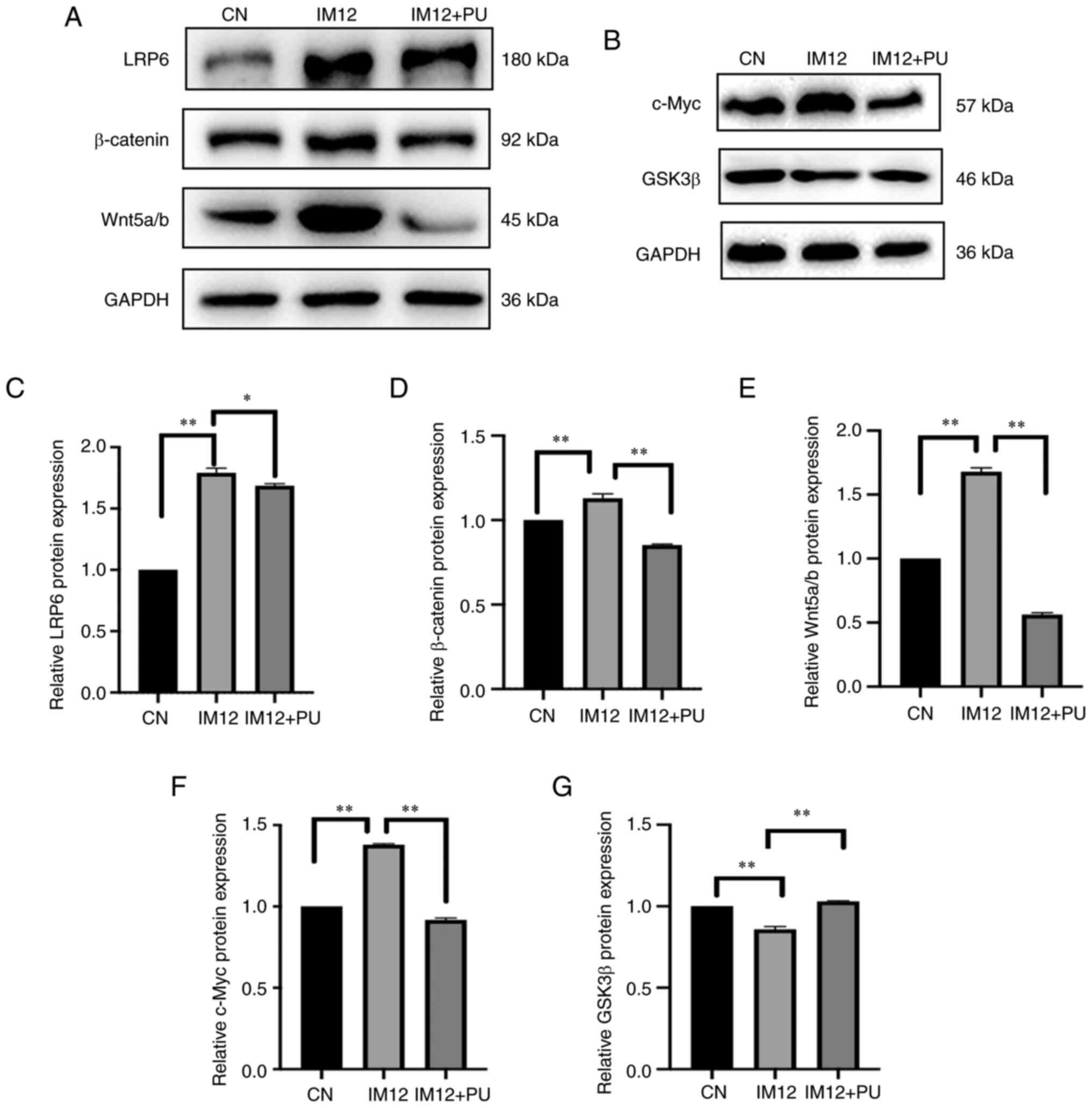

IM-12 enhances Wnt signaling, primarily by

inhibiting GSK-3β (46). In the

present study, IM-12 significantly decreased GSK3β expression

compared with the control (P<0.01; Fig. 7G). The protein expression levels

of LRP6, β-catenin, Wnt-5a/b and c-Myc were significantly increased

by IM-12 compared with the control (P<0.01; Fig. 7A-F). However, protein expression

levels of LRP6 (P<0.05), β-catenin (P<0.01), Wnt-5a/b

(P<0.01) and c-Myc (P<0.01) were significantly decreased by

PU pretreatment. These results suggested that PU suppressed

IM-12-induced activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway.

The effect of IM-12 on expression of markers in the

Wnt signaling pathway and ISO-induced MH in the presence of PU

pretreatment were assessed (Fig.

8). Following treatment with IM-12, PU-induced inhibition of

Wnt signaling pathway protein expression was partially reversed.

With the exception of protein expression of GSK3β, which was

increased by PU but significantly reversed by IM-12 compared with

the PU + ISO group, expression levels of all proteins in the PU +

ISO + IM12 group were significantly increased compared with PU

group (P<0.01). Moreover, the inhibitory effects of PU on the MH

marker ANP was partially but significantly reversed by IM-12

treatment compared with the PU + ISO group (P<0.01). These

results demonstrated that the protective effects of PU on MH may be

mediated by inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway.

Discussion

Despite therapeutic advances, there is a lack of

effective therapeutic treatment strategies for MH. Pathological

cardiac hypertrophy is induced by various factors, including

pressure (47) and volume

overload (48) and pharmaceutical

induction, such as induction using angiotensin II (49) and ISO (50). ISO is a β-receptor agonist that

causes acute myocardial contraction, ischemia, hypoxia and cause

damage to myocardial cells due to production of a large number of

peroxynitrite and oxygen free radicals in rats (51). Prabhu et al (52) reported that activities of

myocardial mitochondrial cathepsin-D and β-glucuronidase are

significantly decreased by high-dose ISO and that ISO decreases

stability of the myocardial mitochondrial membrane. ISO is widely

used to induce MH (50,53). There is evidence demonstrating

that ISO stimulation leads to MH (53). ISO activates MAPK in

cardiomyocytes and phosphorylates Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway

components (54). The increase of

p-ERK1/2 protein expression levels is a downstream effect of

ISO-induced protein kinase C ε activation, which leads to MH

(55). A previous study reported

that chronic infusion of ISO results in compensatory cardiac

hypertrophy associated with protein kinase A activity and

N-terminal cleaved histone deacetylase production (56). The mechanism of ISO-induced

myocardial injury may be associated with oxidative stress, calcium

overload, inflammation and lipid peroxidation (57). It has been confirmed that in

ISO-induced MH, ISO treatment markedly increases reactive oxygen

species levels in cardiomyocytes (58), activates the NF-κB signaling

pathway in AC16 cells and induces an inflammatory response

(59). Further studies are

required to determine the mechanism underlying ISO-induced MH.

Based on a previous study (60),

10 µM ISO was chosen as the induction concentration for the present

study.

In failing human hearts, there is a significant

increase in both mRNA and protein expression of ANP, BNP and β-MHC

(61); whereas expression of

these three genes is normally stable in normal cardiomyocytes

(62,63). A previous study reported that PU

decreases mRNA expression levels of MH markers ANP and BNP in a

dose-dependent manner, with 40 µM being the optimal concentration

(64). Combined with the results

from the present CCK-8 assay, 40 µM was selected as the

concentration to induce MH for subsequent experimentation in the

present study. It has been reported that the early stage of MH is

characterized by the increase of the surface area of cardiomyocytes

(65). Changes in cell surface

area (quantified and analyzed using immunofluorescence) directly

reflect progression of cardiac hypertrophy; this method is used to

assess MH. In a previous study, H9c2 cells were stained with

crystal violet and surface area was observed as a measure of MH to

confirm that the surface area of CD38 knockdown cells was not

enlarged (66). Another study

used wheat germ agglutinin staining to evaluate the size of

cardiomyocytes from heart sections (67). A previous study used surface area

of cells stained with gentian violet to assess MH (68). Studies have also aimed to use cell

surface area to assess the role of miR-339-5p in cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy (69) and determine

the therapeutic potential of pyrroloquinoline quinone for

ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy (59). In the present study, pretreatment

with PU was demonstrated to exert protective effects against

ISO-induced MH, demonstrated by decreased area of cardiomyocytes

and expression of markers of cardiac hypertrophy. Therefore, PU may

be a promising clinical agent for the prevention and treatment of

MH, although its mechanism remains to be fully elucidated.

The signal transduction mechanism underlying MH is

complex. Inflammation (70) and

oxidative stress (71) have both

been previously demonstrated to cause alterations leading to MH and

heart failure. A previous systematic study of Wnt on a genome-wide

level reported an association between MH and the Wnt expression

profile (72). The Wnt signaling

pathway has also been reported to be associated with cardiac

disease; excessive stimulation of Wnt signaling is detrimental to

cardiovascular pathology (42).

PU has been reported to demonstrate anti-inflammatory and

antioxidant activities (73).

However, the potential effects of PU on MH and the Wnt signaling

pathway in cardiomyocytes remain poorly understood. Therefore, the

present study aimed to explore if PU demonstrate effects against MH

in an in vitro model, with specific focus on the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

The Wnt signal transduction pathway is divided into

classical and non-classical branches (74). The present study verified the

expression of associated proteins and demonstrated that PU

inhibited ISO-induced MH by blocking the classical branch of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Wnt signaling is typically

activated by the membrane receptor complex consisting of frizzled

(Fzd), LRP5/6 and disheveled (Dvl) (75). Following activation of the Wnt

receptor, Fzd binds to Wnt protein and LRP5/6 to form a receptor

complex (76). Dvl is recruited

by the receptor complex and activated via phosphorylation before

binding to the β-catenin degradation complex, which separates

β-catenin from the degradation complex to promote stabilization and

aggregation before β-catenin translocates into the nucleus

(77). β-catenin is a core

component of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and is reported to

be upregulated in cardiomyocytes from patients with acute

myocardial infarction and heart tissue of spontaneously

hypertensive rats (78). However,

GSK3β mediates both β-catenin-dependent and -independent cascades

(79). A previous study reported

that GSK3β exerts negative regulatory effects on the Wnt signaling

pathway (80). In the nucleus,

β-catenin binds to T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (Tcf/Lef)

to activate transcription of Wnt target genes (81). c-Myc and Tcf/Lef are downstream

targets of the Wnt signaling pathway; a previous study reported

that activity of these targets is inhibited by low expression of

β-catenin (82).

In the present study, western blotting was used to

assess expression of core proteins in the Wnt signaling pathway;

expression levels of these proteins in the ISO group was

significantly increased but significantly reversed by PU

pretreatment. However, GSK3β protein expression levels exhibited an

opposite trend, which is likely due to its negative regulatory

mechanism of Wnt; following activation of Wnt signaling, activity

of GSK3β is hampered (83). A

previous study reported that decreased expression of GSK3β in

cardiac fibroblasts that led to adverse ventricular remodeling

(84). Therefore, inhibition of

GSK3β may increase the activity of Wnt signaling, thereby leading

to cardiac hypertrophy. PU induces expression of GSK3β, as

demonstrated in the present study, and serves a protective role.

Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that the

Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways exhibit crosstalk and

this interaction is enhanced by the inflammatory response (85,86). In the present study, it was

demonstrated that, in the ISO group, the protein expression of

Wnt5a/b and β-catenin and the phosphorylation levels of p65 were

significantly increased compared with the control but significantly

decreased by pretreatment with PU. These observations are in

accordance with those in previous studies which suggested that

there may be synergy between the two signaling pathways during the

development of MH (87,88). However, more evidence is needed to

support the synergistic effect.

To verify whether inhibition of the Wnt signaling

pathway ameliorated ISO-induced MH, DKK1, an inhibitor of the Wnt

signaling pathway, was used. DKK1 is a member of the DKK family

that is reported to antagonize the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

by decreasing β-catenin and increasing OCT4 expression (89). The results of the present study

demonstrated that the DKK1 group exhibited trends in the expression

of protein in the Wnt signaling pathway that were comparable to

those follow PU pretreatment, in that PU exerted inhibitory effects

on Wnt signaling comparable with those mediated by the known Wnt

inhibitor. IM-12, an activator of the Wnt signaling pathway, has

been reported to increase expression of β-catenin and downstream

proteins while suppressing expression of GSK-3β (46). The present study assessed whether

IM-12 reversed the inhibitory effects of PU on ISO-induced MH, thus

confirming whether PU exerted its effects via inhibition of the Wnt

signaling pathway. The present study demonstrated that PU inhibited

expression of Wnt signaling pathway proteins induced by IM-12 and

increased expression of GSK-3β. Furthermore, IM-12, the specific

activator of the Wnt signaling pathway, was demonstrated to

eliminate the protective effects of PU on MH. In conclusion, PU

served a cardioprotective role partially via inhibition of the Wnt

signaling pathway.

However, in the present study only core proteins in

the Wnt signaling pathway were assessed; therefore the detailed

underlying molecular mechanism in the upstream regulation of

Wnt/β-catenin signaling during MH was not fully elucidated. Since

Wnt signaling induces nuclear localization of β-catenin (90), it is important to determine the

localization and expression of β-catenin. These limitations of the

present study require addressing in future. In future studies, the

inhibitor-like mechanism of PU and its effects on other disease

caused by aberrant activation of the Wnt signaling pathway,

including colon cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic,

lung and ovarian cancer (91),

should be explored.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that

pretreatment of AC16 cells with PU attenuated ISO-induced MH. The

underlying mechanism was associated with inhibition of protein

expression in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and NF-κB

activity. These results suggested that PU may be a potential agent

for treating MH. Based on the importance of the Wnt signaling

pathway for initiation, maintenance, progression and relapse of MH,

PU may serve an inhibitor-like role for the treatment of

cardiovascular and associated disease caused by hyperactivation of

the Wnt signaling pathway. Furthermore, the present study may

provide a novel direction for development and use of agents for MH

treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Shanghai Special Project of

Biomedical Science and Technology (grant no. 21S11901700).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

XW performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote

the manuscript. KH performed experiments and data analysis. LM

designed the study, analyzed data and revised the manuscript. LW

performed data analysis. YY participated in discussions and

analyzed data. YL designed the study and obtained funding. XW, KH,

LM and YL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for participation

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato

G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, Barengo NC, Beaton AZ, Benjamin EJ,

Benziger CP, et al: Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and

risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 76:2982–3021. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cho YS, Moon SC, Ryu KS and Ryu KH: A

study on clinical and healthcare recommending service based on

cardiovascula disease pattern analysis. Int J Biosci Biotechnol.

8:287–294. 2016.

|

|

3

|

Nalban N, Sangaraju R, Alavala S, Mir SM,

Jerald MK and Sistla R: Arbutin attenuates isoproterenol-induced

cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting TLR-4/NF-κB pathway in mice.

Cardiovasc Toxicol. 20:235–248. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Roth GA, Mensah GA and Fuster V: The

global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks: A compass for

global action. J Am Coll Cardiol. 76:2980–2981. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Oh T, Kim D, Lee S, Won C, Kim S, Yang JS,

Yu J, Kim B and Lee J: Machine learning-based diagnosis and risk

factor analysis of cardiocerebrovascular disease based on KNHANES.

Sci Rep. 12:22502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Leong DP, Joseph PG, McKee M, Anand SS,

Teo KK, Schwalm JD and Yusuf S: Reducing the global burden of

cardiovascular disease, part 2: Prevention and treatment of

cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 121:695–710. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Van Camp G: Cardiovascular disease

prevention. Acta Clin Belg. 69:407–411. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhao Y, Jia WW, Ren S, Xiao W, Li GW, Jin

L and Lin Y: Difluoromethylornithine attenuates

isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy by regulating apoptosis,

autophagy and the mitochondria-associated membranes pathway. Exp

Ther Med. 22:8702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gallo S, Vitacolonna A, Bonzano A,

Comoglio P and Crepaldi T: ERK: A key player in the pathophysiology

of cardiac hypertrophy. Int J Mol Sci. 20:21642019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ellison GM, Waring CD, Vicinanza C and

Torella D: Physiological cardiac remodelling in response to

endurance exercise training: Cellular and molecular mechanisms.

Heart. 98:5–10. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Selvetella G, Hirsch E, Notte A, Tarone G

and Lembo G: Adaptive and maladaptive hypertrophic pathways: Points

of convergence and divergence. Cardiovasc Res. 63:373–380. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shimizu I and Minamino T: Physiological

and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

97:245–262. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kurosawa Y, Kojima K, Kato M, Ohashi R,

Minami K and Narita H: Protective action of angiotensin converting

enzyme inhibitors on cardiac hypertrophy in the aortic-banded rat.

Jpn Heart J. 40:645–654. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

A Romero C, Mathew S, Wasinski B, Reed B,

Brody A, Dawood R, Twiner MJ, McNaughton CD, Fridman R, Flack JM,

et al: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors increase

anti-fibrotic biomarkers in African Americans with left ventricular

hypertrophy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 23:1008–1016. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu Y, Shen HJ, Wang XQ, Liu HQ, Zheng LY

and Luo JD: EndophilinA2 protects against angiotensin II-induced

cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting angiotensin II type 1 receptor

trafficking in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biochem.

119:8290–8303. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Walsh-Wilkinson É, Drolet MC, Le Houillier

C, Roy ÈM, Arsenault M and Couet J: Sex differences in the response

to angiotensin II receptor blockade in a rat model of eccentric

cardiac hypertrophy. PeerJ. 7:e74612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chang CS, Tsai PJ, Sung JM, Chen JY, Ho

LC, Pandya K, Maeda N and Tsai YS: Diuretics prevent

thiazolidinedione-induced cardiac hypertrophy without compromising

insulin-sensitizing effects in mice. Am J Pathol. 184:442–453.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Okura T, Miyoshi K, Irita J, Enomoto D,

Jotoku M, Nagao T, Watanabe K, Matsuokan H, Ashihara T, Higaki J,

et al: Comparison of the effect of combination therapy with an

angiotensin II receptor blocker and either a low-dose diuretic or

calcium channel blocker on cardiac hypertrophy in patients with

hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 35:563–569. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang X, Zhang MC and Wang CT: Loss of

LRRC25 accelerates pathological cardiac hypertrophy through

promoting fibrosis and inflammation regulated by TGF-β1. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 506:137–144. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zang Y, Wan J, Zhang Z, Huang S, Liu X and

Zhang W: An updated role of astragaloside IV in heart failure.

Biomed Pharmacother. 126:1100122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ma Y, Kang R and Liu X: Research progress

in prevention and cure of fibrosis by traditional Chinese medicine.

Mod Appl Sci. 2:127–132. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yang QY, Chen KJ, Lu S and Sun HR:

Research progress on mechanism of action of Radix Astragalus in the

treatment of heart failure. Chin J Integr Med. 18:235–240. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Karmazyn M and Gan XT: Treatment of the

cardiac hypertrophic response and heart failure with ginseng,

ginsenosides, and ginseng-related products. Can J Physiol

Pharmacol. 95:1170–1176. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yang J, Wang HX, Zhang YJ, Yang YH, Lu ML,

Zhang J, Li ST, Zhang SP and Li G: Astragaloside IV attenuates

inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting TLR4/NF-кB signaling pathway

in isoproterenol-induced myocardial hypertrophy. J Ethnopharmacol.

150:1062–1070. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu ZH, Liu HB and Wang J: Astragaloside

IV protects against the pathological cardiac hypertrophy in mice.

Biomed Pharmacother. 97:1468–1478. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guo J, Gan XT, Haist JV, Rajapurohitam V,

Zeidan A, Faruq NS and Karmazyn M: Ginseng inhibits cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy and heart failure via NHE-1 inhibition and attenuation

of calcineurin activation. Circ Heart Fail. 4:79–88. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Qin N, Gong QH, Wei LW, Wu Q and Huang XN:

Total ginsenosides inhibit the right ventricular hypertrophy

induced by monocrotaline in rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 31:1530–1535.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bu L, Dai O, Zhou F, Liu F, Chen JF, Peng

C and Xiong L: Traditional Chinese medicine formulas, extracts, and

compounds promote angiogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother.

132:1108552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Luo J, Xu H and Chen K: Systematic review

of compound danshen dropping pill: A chinese patent medicine for

acute myocardial infarction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2013:8080762013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tu Y: Artemisinin-A gift from traditional

Chinese medicine to the world (nobel lecture). Angew Chem Int Ed

Engl. 55:10210–10226. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yang R, Yuan BC, Ma YS, Zhou S and Liu Y:

The anti-inflammatory activity of licorice, a widely used Chinese

herb. Pharm Biol. 55:5–18. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mu F, Duan J, Bian H, Zhai X, Shang P, Lin

R, Zhao M, Hu D, Yin Y, Wen A and Xi M: Metabonomic strategy for

the evaluation of Chinese medicine Salvia miltiorrhiza and

Dalbergia odorifera interfering with myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Rejuvenation Res. 20:263–277.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang S, Zhang S, Wang S, Gao P and Dai L:

A comprehensive review on Pueraria: Insights on its

chemistry and medicinal value. Biomed Pharmacother. 131:1107342020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hou N, Huang Y, Cai SA, Yuan WC, Li LR,

Liu XW, Zhao GJ, Qiu XX, Li AQ, Cheng CF, et al: Puerarin

ameliorated pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in

ovariectomized rats through activation of the PPARα/PGC-1 pathway.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 42:55–67. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yuan G, Shi S, Jia Q, Shi J, Shi S, Zhang

X, Shou X, Zhu X and Hu Y: Use of network pharmacology to explore

the mechanism of Gegen (Puerariae lobatae Radix) in the

treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus associated with

hyperlipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2021:66334022021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhou YX, Zhang H and Peng C: Puerarin: A

review of pharmacological effects. Phytother Res. 28:961–975. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Liu J, Zhang HJ, Ji BP, Cai SB, Wang RJ,

Zhou F, Yang JS and Liu HJ: A diet formula of Puerariae radix,

Lycium barbarum, Crataegus pinnatifida, and Polygonati rhizoma

alleviates insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in CD-1 mice

and HepG2 cells. Food Funct. 5:1038–1049. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu B, Wu Z, Li Y, Ou C, Huang Z, Zhang J,

Liu P, Luo C and Chen M: Puerarin prevents cardiac hypertrophy

induced by pressure overload through activation of autophagy.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 464:908–915. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gao W, Guo N, Zhao S, Chen Z, Zhang W, Yan

F, Liao H and Chi K: Carboxypeptidase A4 promotes cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy through activating PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling. Biosci Rep.

40:BSR202006692020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Foulquier S, Daskalopoulos EP, Lluri G,

Hermans KCM, Deb A and Blankesteijn WM: WNT signaling in cardiac

and vascular disease. Pharmacol Rev. 70:68–141. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Weeks KL, Bernardo BC, Ooi JYY, Patterson

NL and McMullen JR: The IGF1-PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in

mediating exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy and protection. Adv

Exp Med Biol. 1000:187–210. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Fan J, Qiu L, Shu H, Ma B, Hagenmueller M,

Riffel JH, Meryer S, Zhang M, Hardt SE, Wang L, et al: Recombinant

frizzled1 protein attenuated cardiac hypertrophy after myocardial

infarction via the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Oncotarget.

9:3069–3080. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lieven O, Knobloch J and Rüther U: The

regulation of Dkk1 expression during embryonic development. Dev

Biol. 340:256–268. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li Y, Lu W, King TD, Liu CC, Bijur GN and

Bu G: Dkk1 stabilizes Wnt co-receptor LRP6: Implication for Wnt

ligand-induced LRP6 down-regulation. PLoS One. 5:e110142010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang T, Duan YM, Fu Q, Liu T, Yu JC, Sui

ZY, Huang L and Wen GQ: IM-12 activates the Wnt-β-catenin signaling

pathway and attenuates rtPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation in

rats after acute ischemic stroke. Biochem Cell Biol. 97:702–708.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cheng Y, Shen A, Wu X, Shen Z, Chen X, Li

J, Liu L, Lin X, Wu M, Chen Y, et al: Qingda granule attenuates

angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and apoptosis and

modulates the PI3K/AKT pathway. Biomed Pharmacother.

133:1110222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Guo Y, Yu ZY, Wu J, Gong H, Kesteven S,

Iismaa SE, Chan AY, Holman S, Pinto S, Pironet A, et al: The

Ca2+-activated cation channel TRPM4 is a positive

regulator of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Elife.

10:e665822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Schnelle M, Chong M, Zoccarato A, Elkenani

M, Sawyer GJ, Hasenfuss G, Ludwig C and Shah AM: In vivo

[U-13C]glucose labeling to assess heart metabolism in

murine models of pressure and volume overload. Am J Physiol Heart

Circ Physiol. 319:H422–H431. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ma X, Song Y, Chen C, Fu Y, Shen Q, Li Z

and Zhang Y: Distinct actions of intermittent and sustained

β-adrenoceptor stimulation on cardiac remodeling. Sci China Life

Sci. 54:493–501. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ribeiro DA, Buttros JB, Oshima C,

Bergamaschi CT and Campos RR: Ascorbic acid prevents acute

myocardial infarction induced by isoproterenol in rats: Role of

inducible nitric oxide synthase production. J Mol Histol.

40:99–105. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Prabhu S, Narayan S and Devi CS: Mechanism

of protective action of mangiferin on suppression of inflammatory

response and lysosomal instability in rat model of myocardial

infarction. Phytother Res. 23:756–760. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Xu H, Wang Z, Chen M, Zhao W, Tao T, Ma L,

Ni Y and Li W: YTHDF2 alleviates cardiac hypertrophy via regulating

Myh7 mRNA decoy. Cell Biosci. 11:1322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang GX, Kimura S, Murao K, Yu X, Obata

K, Matsuyoshi H and Takaki M: Effects of angiotensin type I

receptor blockade on the cardiac Raf/MEK/ERK cascade activated via

adrenergic receptors. J Pharmacol Sci. 113:224–233. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li L, Cai H, Liu H and Guo T: β-Adrenergic

stimulation activates protein kinase Cε and induces extracellular

signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation and cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy. Mol Med Rep. 11:4373–4380. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Werhahn SM, Kreusser JS, Hagenmüller M,

Beckendorf J, Diemert N, Hoffmann S, Schultz JH, Backs J and

Dewenter M: Adaptive versus maladaptive cardiac remodelling in

response to sustained β-adrenergic stimulation in a new ‘ISO on/off

model’. PLoS One. 16:e02489332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Garg M and Khanna D: Exploration of

pharmacological interventions to prevent isoproterenol-induced

myocardial infarction in experimental models. Ther Adv Cardiovasc

Dis. 8:155–169. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Liu BY, Li L, Liu GL, Ding W, Chang WG, Xu

T, Ji XY, Zheng XX, Zhang J and Wang JX: Baicalein attenuates

cardiac hypertrophy in mice via suppressing oxidative stress and

activating autophagy in cardiomyocytes. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

42:701–714. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Wen J, Shen J, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Dai Z and

Jin Y: Pyrroloquinoline quinone attenuates isoproterenol

hydrochloride-induced cardiac hypertrophy in AC16 cells by

inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 45:873–885.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zhao Y, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Zhang F, Zhang X,

Zhu L and Yao X: Dissection of mechanisms of Chinese medicinal

formula Si-Miao-Yong-an decoction protects against cardiac

hypertrophy and fibrosis in isoprenaline-induced heart failure. J

Ethnopharmacol. 248:1120502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhang C, Wang Y, Ge Z, Lin J, Liu J, Yuan

X and Lin Z: GDF11 attenuated ANG II-induced hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy and expression of ANP, BNP and beta-MHC through

down-regulating CCL11 in mice. Curr Mol Med. 18:661–671. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Cameron VA, Rademaker MT, Ellmers LJ,

Espiner EA, Nicholls MG and Richards AM: Atrial (ANP) and brain

natriuretic peptide (BNP) expression after myocardial infarction in

sheep: ANP is synthesized by fibroblasts infiltrating the infarct.

Endocrinology. 141:4690–4697. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Edwards JG: Cardiac MHC gene expression:

More complexity and a step forward. Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol. 294:H14–H15. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yuan Y, Zong J, Zhou H, Bian ZY, Deng W,

Dai J, Gan HW, Yang Z, Li H and Tang QZ: Puerarin attenuates

pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Cardiol. 63:73–81.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yeh YL, Tsai HI, Cheng SM, Pai P, Ho TJ,

Chen RJ, Lai CH, Huang PJ, Padma VV and Huang CY: Mechanism of

Taiwan Mingjian Oolong tea to inhibit isoproterenol-induced

hypertrophy and apoptosis in cardiomyoblasts. Am J Chin Med.

44:77–86. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Guan XH, Hong X, Zhao N, Liu XH, Xiao YF,

Chen TT, Deng LB, Wang XL, Wang JB, Ji GJ, et al: CD38 promotes

angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Mol Med.

21:1492–1502. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hu H, Jiang M, Cao Y, Zhang Z, Jiang B,

Tian F, Feng J, Dou Y, Gorospe M, Zheng M, et al: HuR regulates

phospholamban expression in isoproterenol-induced cardiac

remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 116:944–955. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Huo S, Shi W, Ma H, Yan D, Luo P, Guo J,

Li C, Lin J, Zhang C, Li S, et al: Alleviation of inflammation and

oxidative stress in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling

and heart failure via IL-6/STAT3 inhibition by raloxifene. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2021:66990542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Bi X, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Yuan J, Xu S, Liu F,

Ye J and Liu P: MiRNA-339-5p promotes isoproterenol-induced

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by targeting VCP to activate the mTOR

signaling. Cell Biol Int. 46:288–299. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Han B, Xu J, Shi X, Zheng Z, Shi F, Jiang

F and Han J: DL-3-n-butylphthalide attenuates myocardial

hypertrophy by targeting gasdermin D and inhibiting gasdermin D

mediated inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 12:6881402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Shah AK, Bhullar SK, Elimban V and Dhalla

NS: Oxidative stress as a mechanism for functional alterations in

cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Antioxidants (Basel).

10:9312021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Gai Z, Wang Y, Tian L, Gong G and Zhao J:

Whole genome level analysis of the Wnt and DIX gene families in

mice and their coordination relationship in regulating cardiac

hypertrophy. Front Genet. 12:6089362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Qin H, Zhang Y, Wang R, Du X, Li L and Du

H: Puerarin suppresses Na+-K+-ATPase-mediated systemic inflammation

and CD36 expression, and alleviates cardiac lipotoxicity in vitro

and in vivo. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 68:465–472. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Moon RT, Kohn AD, De Ferrari GV and Kaykas

A: WNT and beta-catenin signalling: Diseases and therapies. Nat Rev

Genet. 5:691–701. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Agostino M and Pohl SÖ: The structural

biology of canonical Wnt signalling. Biochem Soc Trans.

48:1765–1780. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Hua Y, Yang Y, Li Q, He X, Zhu W, Wang J

and Gan X: Oligomerization of Frizzled and LRP5/6 protein initiates

intracellular signaling for the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway. J

Biol Chem. 293:19710–19724. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Gao C and Chen YG: Dishevelled: The hub of

Wnt signaling. Cell Signal. 22:717–727. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Zeng KW, Wang JK, Wang LC, Guo Q, Liu TT,

Wang FJ, Feng N, Zhang XW, Liao LX, Zhao MM, et al: Small molecule

induces mitochondrial fusion for neuroprotection via targeting CK2

without affecting its conventional kinase activity. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 6:712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Ríos JA, Godoy JA and Inestrosa NC: Wnt3a

ligand facilitates autophagy in hippocampal neurons by modulating a

novel GSK-3β-AMPK axis. Cell Commun Signal. 16:152018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Barker N, Morin PJ and Clevers H: The

Yin-Yang of TCF/beta-catenin signaling. Adv Cancer Res. 77:1–24.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Piazza F, Manni S, Tubi LQ, Montini B,

Pavan L, Colpo A, Gnoato M, Cabrelle A, Adami F, Zambello R, et al:

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates multiple myeloma cell growth

and bortezomib-induced cell death. BMC Cancer. 10:5262010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Guo Y, Gupte M, Umbarkar P, Singh AP, Sui

JY, Force T and Lal H: Entanglement of GSK-3β, β-catenin and TGF-β1

signaling network to regulate myocardial fibrosis. J Mol Cell

Cardiol. 110:109–120. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Guan X, He Y, Wei Z, Shi C, Li Y, Zhao R,

Pan L, Han Y, Hou T and Yang J: Crosstalk between Wnt/β-catenin

signaling and NF-κB signaling contributes to apical periodontitis.

Int Immunopharmacol. 98:1078432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Jia D, Yang W, Li L, Liu H, Tan Y, Ooi S,

Chi L, Filion LG, Figeys D and Wang L: β-Catenin and NF-κB

co-activation triggered by TLR3 stimulation facilitates stem

cell-like phenotypes in breast cancer. Cell Death Differ.

22:298–310. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Shang S, Hua F and Hu ZW: The regulation

of β-catenin activity and function in cancer: Therapeutic

opportunities. Oncotarget. 8:33972–33989. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Gitau SC, Li X, Zhao D, Guo Z, Liang H,

Qian M, Lv L, Li T, Xu B, Wang Z, et al: Acetyl salicylic acid

attenuates cardiac hypertrophy through Wnt signaling. Front Med.

9:444–456. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Olsen NT, Dimaano VL, Fritz-Hansen T,

Sogaard P, Chakir K, Eskesen K, Steenbergen C, Kass DA and Abraham

TP: Hypertrophy signaling pathways in experimental chronic aortic

regurgitation. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 6:852–860. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Liu JJ, Shentu LM, Ma N, Wang LY, Zhang

GM, Sun Y, Wang Y, Li J and Mu YL: Inhibition of NF-κB and

Wnt/β-catenin/GSK3β signaling pathways ameliorates cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy and fibrosis in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1

diabetic rats. Curr Med Sci. 40:35–47. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Ou L, Fang L, Tang H, Qiao H, Zhang X and

Wang Z: Dickkopf Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor 1 regulates the

differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells in vitro and

in vivo. Mol Med Rep. 13:720–730. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Kim S, Song G, Lee T, Kim M, Kim J, Kwon

H, Kim J, Jeong W, Lee U, Na C, et al: PARsylated transcription

factor EB (TFEB) regulates the expression of a subset of Wnt target

genes by forming a complex with β-catenin-TCF/LEF1. Cell Death

Differ. 28:2555–2570. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Zhang L, Guo Z, Wang Y, Geng J and Han S:

The protective effect of kaempferol on heart via the regulation of

Nrf2, NF-κβ, and PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathways in

isoproterenol-induced heart failure in diabetic rats. Drug Dev Res.

80:294–309. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|