Introduction

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) exist within tumors and are

a unique subset of cells with the potential to self-renew,

proliferate indefinitely, and differentiate into tumor cells

(1,2). Present cancer therapies are known to

leave behind some CSCs, explaining why tumor eradication is

difficult to achieve (3–5). While the development of CSC-specific

drugs may bring new hope to cancer therapy, there are few

established models that allow the isolation and the study of

CSCs.

Previous findings have shown that aldehyde

dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) can be used as a CSC marker and is

expressed in many stem cell types, including breast, lung,

neuronal, and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (6,7). ALDH1

is a member of a family of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes that

oxidize acetaldehyde to acetic acid. In HSCs, ALDH1 can control

retinol metabolism, and certain classes of retinoic acid may lead

to the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (8). By contrast, immature HSCs are very

rich in retinol, which enhances self-renewal (9). The above-mentioned results suggest

that ALDH1 is a necessary factor for the HSC environment. A

fluorescent ALDH substrate that passes through the cell membrane by

free diffusion (Aldefluor® BAAA-ALDH) can be used to

measure ALDH enzyme activity by quantitative flow cytometry

(10–12).

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) was identified

and designated as such in the 1960s. However, the prognostic

factors that are predictive of MFH outcome have not been well

described (13). The majority of

MFH tumors are defined as pleomorphic subtypes, and a few myxoid

MFH cell lines have been established (14–16).

Kawashima et al established the NMFH-1 cell line, which may

prove a useful tool for studying CSCs (17).

In the present study, we isolated and characterized

the population of NMFH-1 cells that have ALDH enzymatic activity, a

trait characteristic of CSCs. The aim was to develop a model for

the study of CSCs, which may ultimately provide insights into the

clinical treatment of MFH. At present, it remains unknown whether

the population of ALDH+ cells may be isolated from the

human NMFH-1 cell line. Therefore, we defined the population of

NMFH-1 cells with high ALDH enzymatic activity on CSC phenotypes.

The findings may impact on the development of more effective MFH

therapies.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

The human NMFH-1 cell line used in the present study

was obtained from the Niigata University Graduate School of Medical

and Dental Sciences (17) and

maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in RPMI-1640

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Aldefluor® (Stem Cell Technologies, Durham, NC, USA) was

used to isolate the cell populations with high levels of the ALDH

enzymatic activity. The cells were labeled with

Aldefluor® reagent by collecting cells using 0.25%

trypsin according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and

single-cell suspension was prepared. The cells were washed with PBS

and isolated by centrifugation prior to adding the product reagent

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ALDH+

and ALDH− cells were then analyzed or isolated using a

FACSAria.

Sphere formation

A single-cell suspension of 1×105

ALDH+ or ALDH− cells in serum-free RPMI-1640

medium was seeded in 6-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, New

York, USA). Each well contained 20 μg/l of EGF and bFGF, and

wells were supplemented with 2 μg/l of EGF and bFGF every 24

h until spherical cell formations appeared. Following sphere

formation, the cells were collected in a common culture bottle with

complete media to observe whether the cells could be adhered to the

wall. Other spheres were disrupted into a signal-cell solution to

assess whether a second sphere could form.

Tumor implantation in nude BALB/c

mice

Cells were collected and suspended and the

concentration was adjusted with culture medium. The cells were

injected into the left side of the front leg of BALB/c nude mice (6

weeks; weight, 18–22 g) obtained from the Animal Research Center,

Harbin Medical University, China. The mice were separated into 10

groups of 5 animals and received varying concentrations of the

ALDH+ or ALDH− cells. After 6 weeks, the mice

were sacrificed and any tumors were removed for histopathological

and immunohistochemical analysis. Tumor samples were also digested

using collagenase II (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and

re-injected into mice to generate second-round tumors. Data were

collected from three independent experiments.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical

analysis of xenografts

The ALDH+ and ALDH− tumors

were placed in flasks with 10% formalin, and then embedded in

paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E) using a standard protocol to assess tumor type. An ALDH1

antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was used to

determine the ALDH1 expression levels in the tumor by

immunohistochemistry.

Chemoresistance of cell monolayers and

spheres

Cells were transferred to 96-well plates at a

density of 2×103 cells/well in RPMI-1640 culture medium

with 10% FBS. Increasing concentrations of the drugs doxorubicin

(DXR) or cisplatin (CDDP) (Sigma-Aldrich) were added in triplicate

and incubated for 40 h (1, 5 and 10 μM). CCK-8 (10

μl) was placed in each well. The OD value was measured at

450 nm. Cell viability was measured using the Cell Titer 96 AQueous

One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega), according to

the manufacturer’s instructions. In addition, we compared drug

resistance between the ALDH+ spheroid and adherent

cells.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from both the

ALDH+ and ALDH− cells. We quantified the mRNA

transcription levels of highly expressed genes in stem cells, i.e.,

c-Myc, Bmi-1, Sox2, Nanog,

Oct3/4, and STAT3. We also assessed the expression

levels of the drug-resistant genes, ABCG2 and ALDH1.

β-actin was used as an internal control. The primer sequences used

for amplification are listed in Table

I.

| Table IPCR primers used in this study. |

Table I

PCR primers used in this study.

| Target gene | Primer

sequences | Size (bp) |

|---|

| c-Myc | F:

5′-TCCCTCCACTCGGAAGGAC-3′

R: 5′-CTGGTGCATTTTCGGTTGTTG-3′ | 96 |

| Nanog | F:

5′-TTTGTGGGCCTGAAGAAAACT-3′

R: 5′-AGGGCTGTCCTGAATAAGCAG-3′ | 116 |

| Sox-2 | F:

5′-GCCGAGTGGAAACTTTTGTCG-3′

R: 5′-GGCAGCGTGTACTTATCCTTCT-3′ | 155 |

| Bmi-1 | F:

5′-CGTGTATTGTTCGTTACCTGGA-3′

R: 5′-TTCAGTAGTGGTCTGGTCTTGT-3′ | 82 |

| ABCG2 | F:

5′-ACGAACGGATTAACAGGGTCA-3′

R: 5′-CTCCAGACACACCACGGAT-3′ | 93 |

| STAT3 | F:

5′-CAGCAGCTTGACACACGGTA-3′

R: 5′-AAACACCAAAGTGGCATGTGA-3′ | 150 |

| ALDH1 | F:

5′-GCACGCCAGACTTACCTGTC-3′

R: 5′-CCTCCTCAGTTGCAGGATTAAAG-3′ | 129 |

| Oct3/4 | F:

5′-GTGTTCAGCCAAAAGACCATCT-3′

R: 5′-GGCCTGCATGAGGGTTTCT-3′ | 156 |

| β-actin | F:

5′-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-3′

R: 5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3′ | 250 |

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described

previously, with some modifications (18). Briefly, the cells were washed twice

with cold PBS and lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH

7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 1% Na

deoxycholate, 1 mM Na vanadate and protease inhibitors (5 mg/ml

pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF, 10 mg/ml leupeptin and 1 mM NaF;

Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h on ice. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g

for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant protein concentrations were

measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology,

Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). Membranes were blocked with non-fat milk

for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with the

corresponding antibodies in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 5% BSA

(Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% Tween-20 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules,

CA, USA). After washing three times in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20, the

blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA;

Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA).

Immunoreactive bands were detected with the ECL Plus SuperSignal

West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham,

MA, USA) for 60 sec. Protein levels were normalized with respect to

the band density of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

(GAPDH) as an internal control. The primary antibodies used were:

anti-ABCG2 (1:1,000), anti-Bmi-1 (1:1,000), anti-c-Myc (1:1,000),

anti-Nanog (1:1,000), anti-Oct3/4 (1:1,000), anti-Sox2 (1:1,000),

anti-STAT3 (1:1,000), and anti-ALDH1 (1:1,000) (all from Cell

Signaling Technology), and anti-GAPDH (1:5,000) (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The statistical software SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data processing and analyzing. Data

are presented as the means ± SD, and a comparison was carried

between experimental groups of qPCR analysis using one-way ANOVA.

The results of the chemosensitivity assay were calculated and

compared using one-way ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Separation and differentiation of the

ALDH+ and ALDH− populations from the human

NMFH-1 cell line

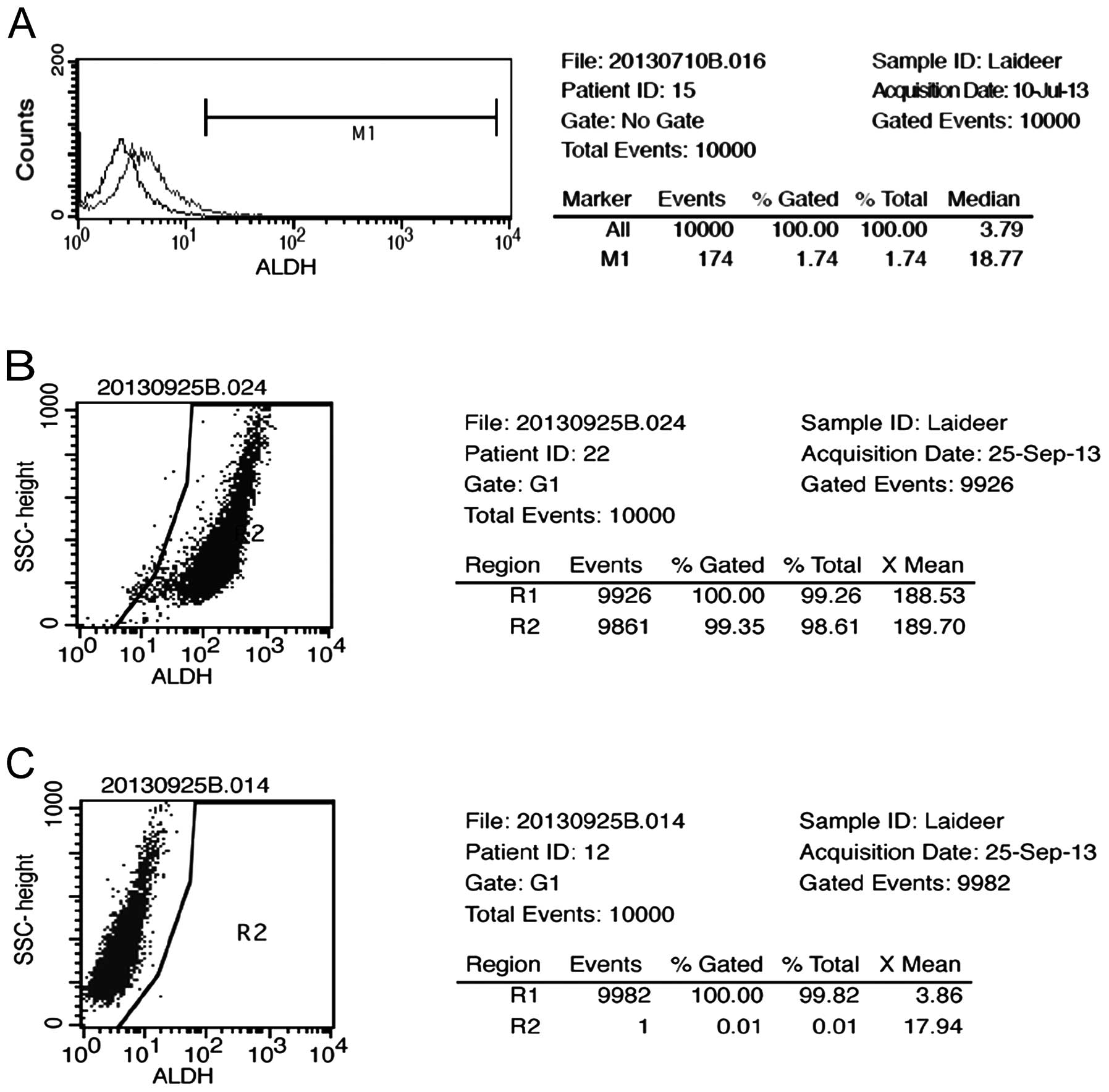

We assessed the presence and size of the NMFH-1 cell

population with the ALDH enzymatic activity by Aldefluor assay. A

small (1.74%) but detectable cell population was identified

(Fig. 1A). The ALDH+ and

ALDH− cells were isolated by FACSAria-based cell

sorting, and the content of each population was verified after

separation. The ALDH+ population reached 98.61% purity

(Fig. 1B), and the ALDH−

population reached 99.82% purity (Fig.

1C).

ALDH+ cells exhibit enhanced

sphere formation

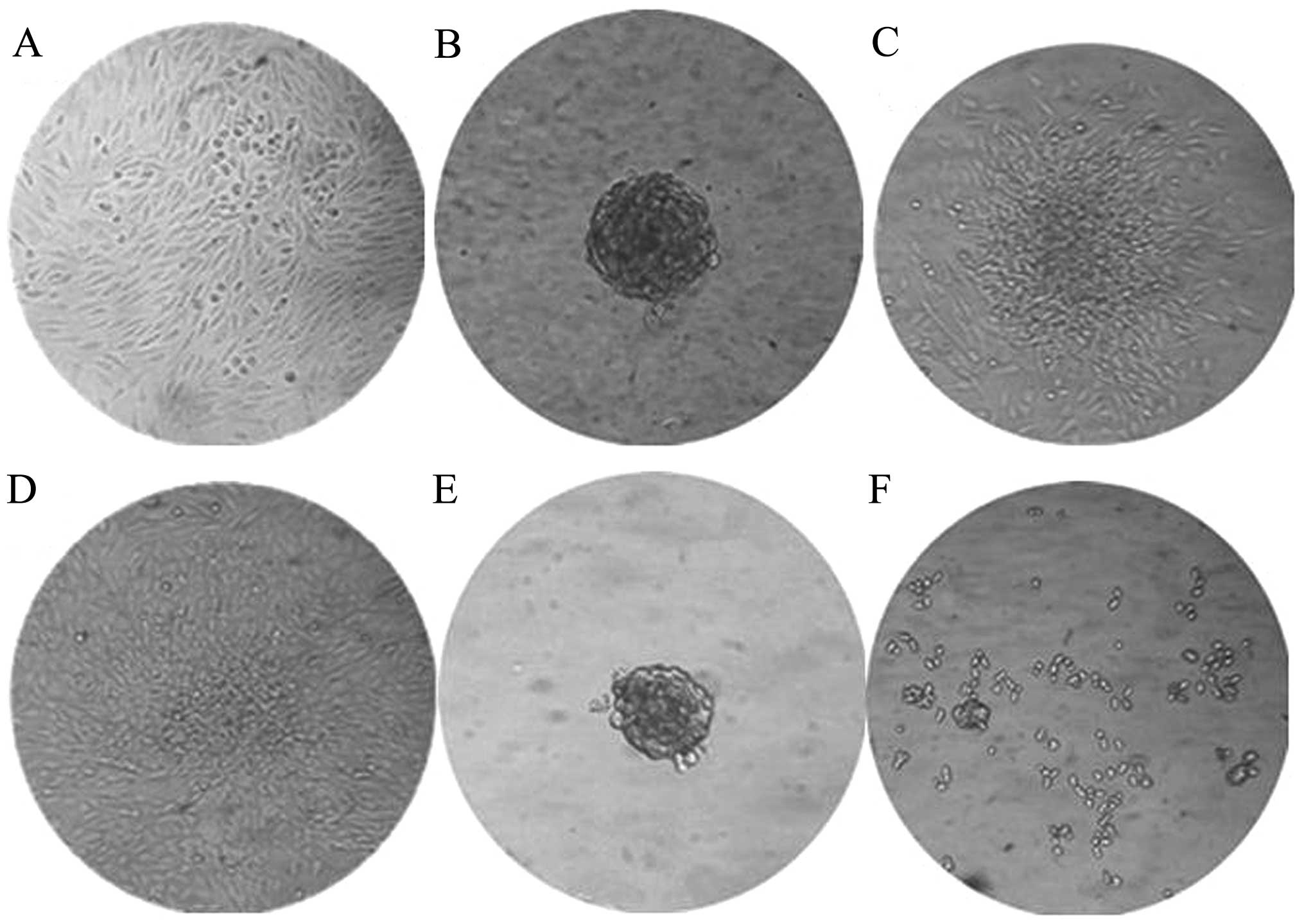

The ALDH+ cells formed many spheroids

when cultured in suspension with serum-free medium. This method was

initially developed to select neural stem cells, but has been

adapted as a general tumor-initiating cell selection method. The

cells grew normally under these conditions (Fig. 2A), but growth in

EGF/bFGF-supplemented medium has been shown to allow spherical

clones to develop from normal cells and CSCs of epithelial origin.

The ALDH+ cells formed a small sphere on the third day,

which became clearly visible by the fifth day (Fig. 2B). In comparison, 10 days were

required for the ALDH− cells to develop spheres that

were smaller than those formed by the ALDH+ populations

(Fig. 2F). The ALDH+

spheres could be transferred into complete media containing serum

and the cells were able to adhere for continued growth (Fig. 2C and D).

ALDH+ cells exhibit enhanced

tumor development in BALB/c nude mice

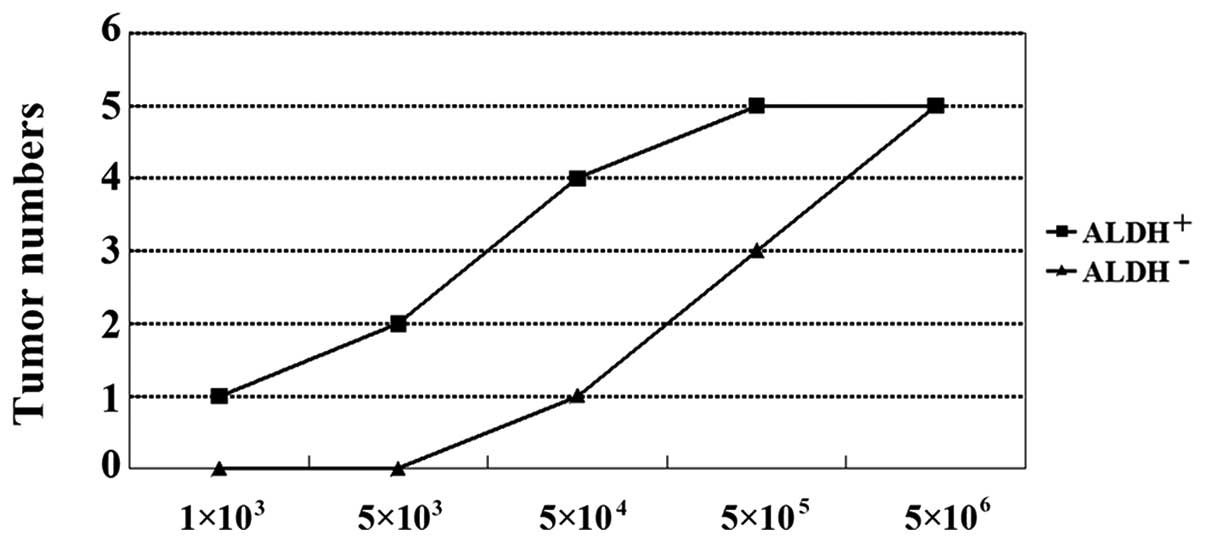

The implantation of cancer cells into nude mice can

lead to tumor development. In order to evaluate the tumor

development potential of the ALDH+ and ALDH−

cells, we injected them into BALB/c nude mice to generate

xenografts. Six weeks following the injection, the mice were

euthanized and assayed for tumor development (Table II). As few as 1×103

ALDH+-injected cells were required for tumor growth. By

contrast, 5×104 ALDH− cells were required to

develop similar tumors (Figs. 3 and

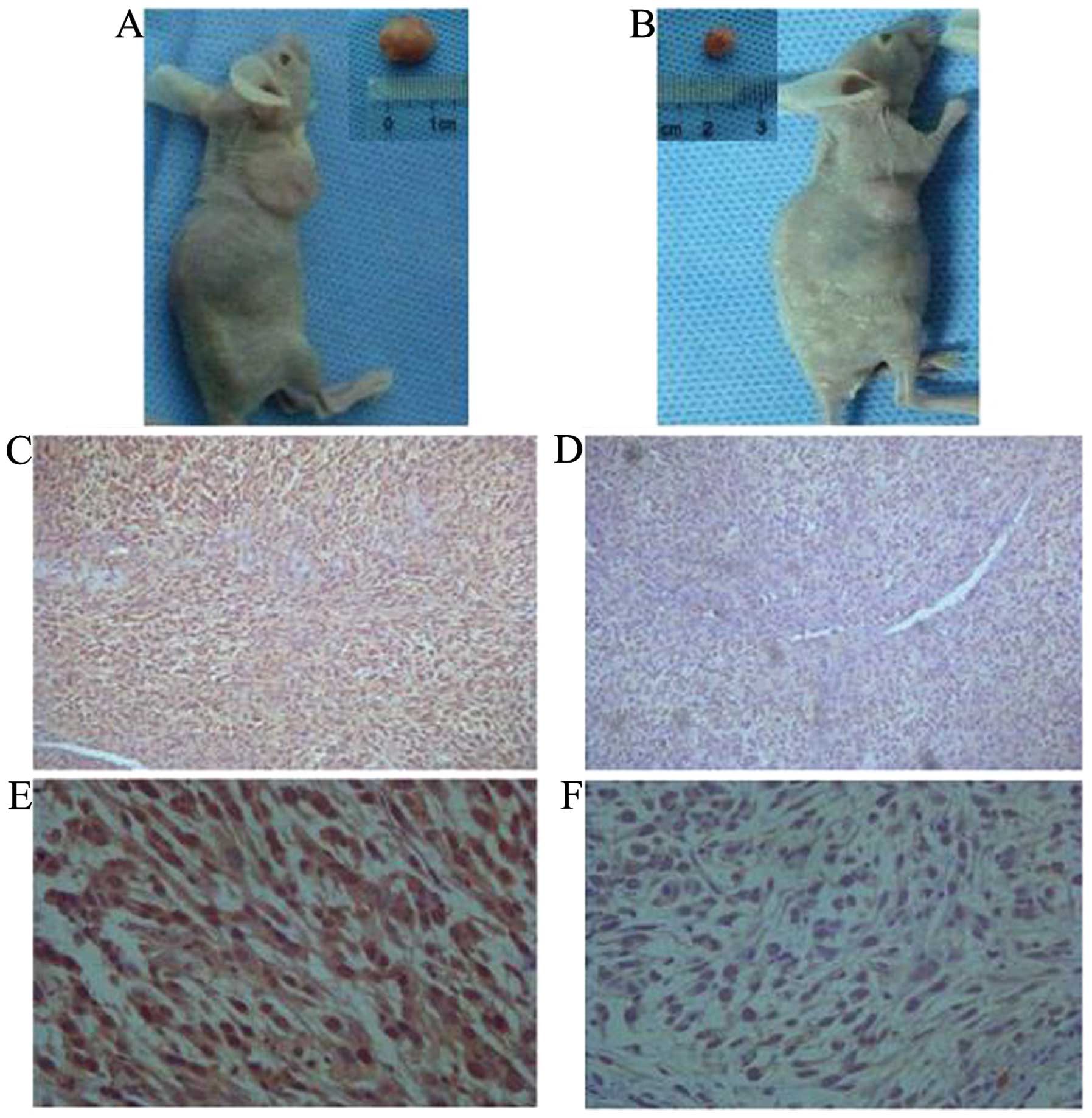

4A and B). H&E staining

indicated that the ALDH+ and ALDH−-induced

tumors have histological differences. Furthermore,

ALDH+-induced tumors had a higher ALDH1 expression as

determined by immunostaining (Fig.

4C–F). These results suggested that ALDH1 may be the gene

responsible for the selected ALDH enzymatic activity.

| Table IITumor-initiating capacity of

ALDH+ and ALDH− populations. |

Table II

Tumor-initiating capacity of

ALDH+ and ALDH− populations.

| Populations | Cell planting

|

|---|

|

1×103 |

5×103 |

5×104 |

5×105 |

5×106 |

|---|

|

ALDH+ | 1/5 | 2/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

|

ALDH− | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 3/5 | 5/5 |

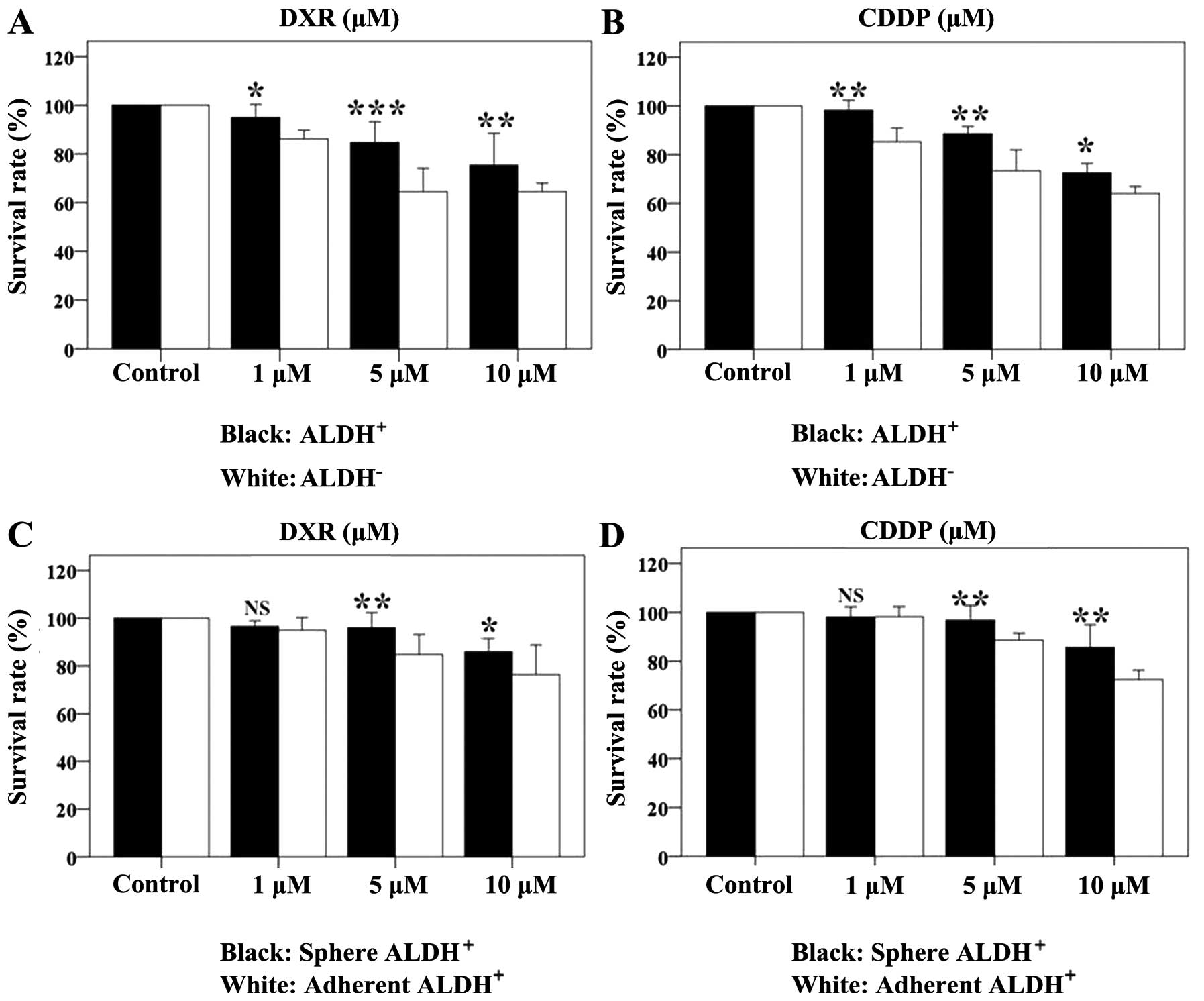

Drug efficacy on cell monolayers and

spheres

The results showed DXR and CDDP have dose-dependent

effects on cell survival. The ALDH+ and ALDH−

cell survival rate was determined after 48-h drug treatments

(Table III and IV, Fig.

5). DXR and CDDP killed the two cell populations; however, the

ALDH+ cells were more resistant to the drugs than the

ALDH− cells. In order to further validate the resistance

of the ALDH+ cells, we compared the drug response of

spheroid and adherent cells. The rate of growth inhibition of the

ALDH+ spheroids was slightly higher than that of

adherent cells in response to the two drugs (Table IV, Fig.

5C and D).

| Table IIIALDH+ and ALDH−

cell survival rates (%) after 48-h treatment with DXR or CDDP. |

Table III

ALDH+ and ALDH−

cell survival rates (%) after 48-h treatment with DXR or CDDP.

| DXR

| CDDP

|

|---|

| 1 μM | 5 μM | 10 μM | 1 μM | 5 μM | 10 μM |

|---|

|

ALDH+ | 94.92±2.16 | 84.69±3.41 | 76.34±4.99 | 98.19±1.67 | 88.57±1.17 | 72.40±1.60 |

|

ALDH− | 86.18±1.39 | 64.56±3.83 | 64.56±1.39 | 85.25±2.26 | 73.31±3.48 | 64.08±1.14 |

| F-value | 11.86 | 89.68 | 49.78 | 52.44 | 51.88 | 11.15 |

| P-value | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.029 |

| Table IVSpherical and adherent cell survival

rates (%) after 48-h treatment with DXR or CDDP. |

Table IV

Spherical and adherent cell survival

rates (%) after 48-h treatment with DXR or CDDP.

| DXR

| CDDP

|

|---|

| 1 μM | 5 μM | 10 μM | 1 μM | 5 μM | 10 μM |

|---|

| Sphere | 96.4±0.78 | 95.95±2.58 | 85.90±2.22 | 98.11±1.68 | 96.80±2.43 | 85.58±3.77 |

| Adhere | 94.92±2.16 | 84.69±3.41 | 76.34±4.99 | 98.19±1.67 | 88.57±1.17 | 72.40±1.60 |

| F-value | 1.035 | 20.83 | 9.019 | 0.000 | 28.00 | 31.11 |

| P-value | 0.310 | 0.010 | 0.039 | 0.960 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

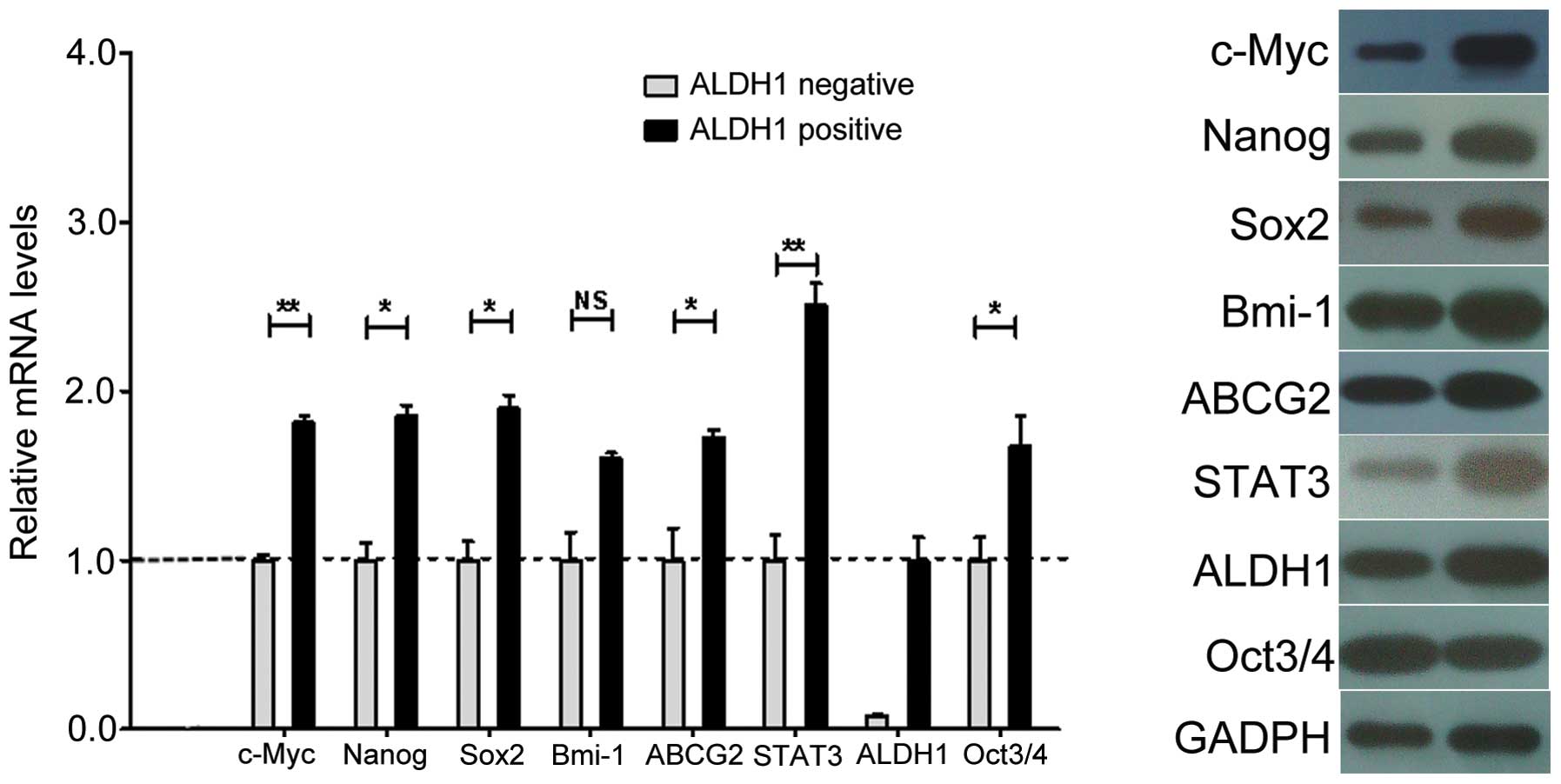

qPCR

Stemness and drug transporter genes are

characteristic of CSCs. To determine whether the NMFH-1

subpopulations shared these characteristics, we measured the

expression of the c-Myc, Bmi-1, Sox2,

Nanog, Oct3/4, STAT3, ABCG2 and

ALDH1 genes (19–21). The ALDH+ population had

increased levels of ALDH1 gene expression. Therefore the CSC

population that we isolated can also be referred to as

ALDH1+. We found that Bmi-1 expression was not

significantly different between the ALDH+ and

ALDH− cells. However, the expression of c-Myc,

STAT3, Sox2, Nanog, Oct3/4, and

ABCG2 was significantly increased in the ALDH+

cells as measured by mRNA transcript levels (Fig. 6A). However, the expression of Oct3/4

protein was not higher in the ALDH+ cells compared with

the ALDH− cells (Fig.

6B). The transcription and protein expression of the ABCG2 drug

transporter was significantly increased in the ALDH+

cells compared with the ALDH− cells. Thus, these data

demonstrated that the NMFH-1 cells have an ALDH+

subpopulation that expresses genes highly associated with stem

cells.

Discussion

Tumors are difficult to cure due to the existence of

CSCs, which have the potential for self-renewal, unlimited

proliferation, and differentiation into tumor cells (1,2).

Previous findings confirm that CSCs exist in many tumor tissues.

However, the isolation of CSCs to develop improved cancer

treatments in the future remains to be investigated.

In 1996, the identification of a side population

(SP) of cells was proposed as a new method for stem cell

separation. The SP, defined by Hoechst 33342 dye exclusion, was

identified as a distinct subset of cells. These cells have

subsequently been isolated and designated CSCs because they possess

stemness characteristics and are responsible for tumorigenesis in

several cancer types (22–25).

In 2003, Al-Hajj et al (26) isolated CSCs (~2%) from breast cancer

specimens with the cell surface markers

CD24−CD44+Lin−, and verified that

these cells were highly tumorigenic. Another series of cell surface

markers, such as CD133, CD90, CD44, CD34, and CD38 have also been

used to isolate CSCs (27–31). These specific surface markers are

mostly present in solid tumors. However, stem cells from different

tissues may express unique markers.

ALDH1 has recently been identified as a marker for

CSCs in humans, because many types of stem cells express ALDH1 at

high levels. This observation has been confirmed in breast stem

cells, HSCs, neural stem cells, prostate, colon and lung CSCs

(6,7,32–36).

As a functional protease, the gene is more common than the cell

surface markers. Confirmation that all the stem cells express high

levels of ALDH1+ may provide a reliable method for the

isolation of the CSCs. Our results show that 1.74% of the NMFH-1

cells are ALDH+. We also found that the survival rate

following the freeze-thaw of the ALDH+ cells was

significantly higher than that in the ALDH− cells.

However, subsequent generations of these cells did not have

significant growth defects. It is possible that the low temperature

had a specific-temporary effect on the growth of the

ALDH− cells.

The results showed that the ALDH+ NMFH-1

cells are more capable of forming spheres when cultured in

serum-free medium than the ALDH− cells, and these cells

can form spheres a second time. The ALDH− cells required

longer time periods and formed smaller spheres. These spheres may

have been formed by the CSCs of other subpopulations marked by

CD133, CD44 or other markers. It is possible that ALDH selection

could isolate most of the stem cells but not all of them; however,

this remains to be demonstrated. The ability of the

ALDH+ cells to form tumors in nude mice is very

apparent. Briefly, 1×103 ALDH+ cells grown in

nude mice subcutaneously formed a tumor, whereas 5×104

ALDH− cells did not form tumor in nude mice.

Furthermore, the ALDH+ cells formed larger tumors than

the ALDH− cells during the same time-period. Previous

studies have indicated that 500 ALDH+ cells can form

tumors but 5,000 ALDH− cells are required to form tumors

(6). Our experiments required more

cells which may be an indication of differences in the laboratory

conditions, personnel operation, or experimental design.

Immunohistochemistry confirmed that the tumors developed from the

ALDH+ cells expressed high levels of the ALDH1 protein

in mice. By contrast, low levels of the ALDH1 protein were

expressed in tumors developed from the ALDH− cells.

Thus, it can be hypothesized that the ALDH1+ cells

contribute to tumor formation, which is consistent with these cells

being CSCs. In the present study, ALDH1 expression was maintained

even after several rounds of division in vivo. However, in

ordinary tumor cells, the content of ALDH1 is very limited.

Survival competition of the ALDH1− cells may account for

this phenomenon by secreting some factors that limit the

ALDH1+ cell proliferation. However, this remains an open

area of research.

We compared the expression of genes that play a

prominent role in stem cell maintenance, self-renewal, and nuclear

reprogramming. These included c-Myc, Bmi-1,

Sox2, Nanog, Oct3/4 and STAT3 in

ALDH+ and ALDH− cells. If these cells

expressed these genes at high levels, they could not all be defined

as CSCs. We used ALDH enzymatic activity as the marker for

isolation and we detected ALDH1 gene expression in both the

ALDH+ and ALDH− cells. qPCR assays showed

that the expression of c-Myc and STAT3 was

significantly different between populations (P<0.01). c-Myc

regulates the G0-G1 cell cycle transition and promotes cell

division. It has also been shown to control infinite rounds of

proliferation and the development of tumor formation. Many growth

factors can stimulate fibroblast cells, which can lead to an

enhanced c-Myc expression. Bmi-1 emerged as a Myc-cooperating

oncogene (37–39). STAT3 is a signal transduction factor

and an important member of a family of activating factors. The STAT

signaling pathways are closely associated with cell proliferation,

differentiation and apoptosis. Activation of the pathway can lead

to abnormal cell proliferation and malignant transformation

(35,40). The expression of Sox2, Nanog, and

Oct3/4 was significantly different between the ALDH+ and

ALDH− populations (P<0.05). Sox2 and Oct3/4 can

cooperate to control fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4). FGF4 is a

signaling molecule that plays an important role in embryonic

development, and the FGF4 gene has a specific enhancer

element in the 3′UTR (41–43). Nanog encodes a recently identified

divergent homeoprotein that controls cell self-renewal (44).

In the drug resistance experiment, we found that the

NMFH-1 ALDH+ cells were more resistant than the

ALDH− cells. Moreover, the ALDH+-derived

spheres showed greater resistance than the ALDH+

adherent cells. In clinical practice, MFH is difficult to cure and

is not sensitive to these drugs. Comprehensive surgery, radiation,

and chemotherapy are known treatment methods used to improve the

resection and survival rates, and reduce the local recurrence rate

of MFH (45,46). ABCG2 expression is reported to

significantly contribute to the CSC phenotype, strongly correlate

with drug resistance, and indicate a poor clinical outcome

(47,48). The mRNA expression of the

ABCG2 gene between populations had a significant difference,

as shown by the RT-PCR results. In the ALDH+ cells, the

ABCG2 protein expression was higher than that in the

ALDH− cells, which potentially accounts for

ALDH+ cell drug resistance.

In conclusion, our study is the first to

successfully isolate the ALDH+ subpopulation from the

NMFH-1 cell line. The experiments also show that the

ALDH+ subpopulation exhibits several characteristic CSC

properties, including high clonogenicity and self-renewal,

increased chemotherapeutic drug resistance, elevated expression of

stemness and drug transporter genes and high tumorigenic potential.

The above results show that ALDH1 can be used as a marker for

isolation of the CSCs from the NMFH-1 cell line. We hypothesize

that ALDH1 may be used as a biomarker for stem cell specificity and

applied to other tumors. ALDH1 expression may also play a future

role in the development of clinical treatments.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81072192). We

would like to thank Dr Akira Ogose (Division of Orthopedic Surgery,

Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences,

Niigata, Japan) for providing the NMFH-1 cell line.

References

|

1

|

Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF and

Weissman IL: Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature.

414:105–111. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Molofsky AV, Pardal R and Morrison SJ:

Diverse mechanisms regulate stem cell self-renewal. Curr Opin Cell

Biol. 16:700–707. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fabrizi E, di Martino S, Pelacchi F and

Ricci-Vitiani L: Therapeutic implications of colon cancer stem

cells. World J Gastroenterol. 16:3871–3877. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Piscaglia AC: Stem cells, a two-edged

sword: risks and potentials of regenerative medicine. World J

Gastroenterol. 14:4273–4279. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Di J, Duiveman-de Boer T, Figdor CG and

Torensma R: Aiming to immune elimination of ovarian cancer stem

cells. World J Stem Cells. 5:149–162. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E,

et al: ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem

cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell.

1:555–567. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, et al: Aldehyde

dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung

cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 7:330–338. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Purton LE: Roles of retinoids and retinoic

acid receptors in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell

self-renewal and differentiation. PPAR Res. 2007:879342007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Purton LE, Bernstein ID and Collins SJ:

All-trans retinoic acid delays the differentiation of primitive

hematopoietic precursors (lin-c-kit+Sca-1(+)) while enhancing the

terminal maturation of committed granulocyte/monocyte progenitors.

Blood. 94:483–495. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Jones RJ, Barber JP, Vala MS, Collector

MI, Kaufmann SH, Ludeman SM, Colvin OM and Hilton J: Assessment of

aldehyde dehydrogenase in viable cells. Blood. 85:2742–2746.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Storms RW, Trujillo AP, Springer JB, Shah

L, Colvin OM, Ludeman SM and Smith C: Isolation of primitive human

hematopoietic progenitors on the basis of aldehyde dehydrogenase

activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 96:9118–9123. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hess DA, Meyerrose TE, Wirthlin L, Craft

TP, Herrbrich PE, Creer MH and Nolta JA: Functional

characterization of highly purified human hematopoietic

repopulating cells isolated according to aldehyde dehydrogenase

activity. Blood. 104:1648–1655. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Corpron CA, Black CT, Raney RB, Pollock

RE, Lally KP and Andrassy RJ: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma in

children. J Pediatr Surg. 31:1080–1083. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kanzaki T, Kitajima S and Suzumori K:

Biological behavior of cloned cells of human malignant fibrous

histiocytoma in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Res. 51:2133–2137.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Schmidt H, Körber S, Hinze R, Taubert H,

Meye A, Würl P, Holzhausen HJ, Dralle H and Rath FW: Cytogenetic

characterization of ten malignant fibrous histiocytomas. Cancer

Genet Cytogenet. 100:134–142. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Meloni-Ehrig AM, Chen Z, Guan XY,

Notohamiprodjo M, Shepard RR, Spanier SS, Trent JM and Sandberg AA:

Identification of a ring chromosome in a myxoid malignant fibrous

histiocytoma with chromosome microdissection and fluorescence in

situ hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 109:81–85. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kawashima H, Ogose A, Gu W, et al:

Establishment and characterization of a novel myxofibrosarcoma cell

line. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 161:28–35. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gibbs CP, Kukekov VG, Reith JD,

Tchigrinova O, Suslov ON, Scott EW, Ghivizzani SC, Ignatova TN and

Steindler DA: Stem-like cells in bone sarcomas: implications for

tumorigenesis. Neoplasia. 7:967–976. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Okita K, Ichisaka T and Yamanaka S:

Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells.

Nature. 448:313–317. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Takahashi K and Yamanaka S: Induction of

pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast

cultures by defined factors. Cell. 126:663–676. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink

T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE and Jaenisch R: In vitro

reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state.

Nature. 448:318–324. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lathia JD: Cancer stem cells: moving past

the controversy. CNS Oncol. 2:465–467. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Haraguchi N, Utsunomiya T, Inoue H, Tanaka

F, Mimori K, Barnard GF and Mori M: Characterization of a side

population of cancer cells from human gastrointestinal system. Stem

Cells. 24:506–513. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng YW, Yokosuka O,

Saisho H, Iwama A, Nakauchi H and Taniguchi H: Side population

purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem

cell-like properties. Hepatology. 44:240–251. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos

PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, Dombkowski D, Preffer F,

Maclaughlin DT and Donahoe PK: Ovarian cancer side population

defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and mullerian

inhibiting substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:11154–11159. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A,

Morrison SJ and Clarke MF: Prospective identification of

tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

100:3983–3988. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Eramo A, Lotti F, Sette G, Pilozzi E,

Biffoni M, Di Virgilio A, Conticello C, Ruco L, Peschle C and De

Maria R: Identification and expansion of the tumorigenic lung

cancer stem cell population. Cell Death Differ. 15:504–514. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Lau CK, Yu WC, Ngai

P, Chu PW, Lam CT, Poon RT and Fan ST: Significance of

CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer

Cell. 13:153–166. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS

and Mulligan RC: Isolation and functional properties of murine

hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med.

183:1797–1806. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Armstrong L, Stojkovic M, Dimmick I, Ahmad

S, Stojkovic P, Hole N and Lako M: Phenotypic characterization of

murine primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells isolated on basis

of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Stem Cells. 22:1142–1151. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang Y, Thant AA, Machida K, Ichigotani

Y, Naito Y, Hiraiwa Y, Senga T, Sohara Y, Matsuda S and Hamaguchi

M: Hyaluronan-CD44s signaling regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2

secretion in a human lung carcinoma cell line QG90. Cancer Res.

62:3962–3965. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hess DA, Wirthlin L, Craft TP, Herrbrich

PE, Hohm SA, Lahey R, Eades WC, Creer MH and Nolta JA: Selection

based on CD133 and high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity isolates

long-term reconstituting human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood.

107:2162–2169. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Seigel GM, Campbell LM, Narayan M and

Gonzalez-Fernandez F: Cancer stem cell characteristics in

retinoblastoma. Mol Vis. 11:729–737. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ivashkiv LB: Jak-STAT signaling pathways

in cells of the immune system. Rev Immunogenet. 2:220–230.

2000.

|

|

35

|

Kim H, Lapointe J, Kaygusuz G, Ong DE, Li

C, van de Rijn M, Brooks JD and Pollack JR: The retinoic acid

synthesis gene ALDH1a2 is a candidate tumor suppressor in prostate

cancer. Cancer Res. 65:8118–8124. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, Ginestier C,

Dontu G, Appelman H, Fields JZ, Wicha MS and Boman BM: Aldehyde

dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic

stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon

tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 69:3382–3389. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Brunk BP, Martin EC and Adler PN:

Drosophila genes posterior sex combs and suppressor two of zeste

encode proteins with homology to the murine bmi-1 oncogene. Nature.

353:351–353. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Iwama A, Oguro H, Negishi M, et al:

Enhanced self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells mediated by the

polycomb gene product Bmi-1. Immunity. 21:843–851. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lessard J and Sauvageau G: Bmi-1

determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem

cells. Nature. 423:255–260. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ning ZQ, Li J, McGuinness M and Arceci RJ:

STAT3 activation is required for Asp(816) mutant c-Kit induced

tumorigenicity. Oncogene. 20:4528–4536. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Maucksch C, Jones KS and Connor B: Concise

review: the involvement of SOX2 in direct reprogramming of induced

neural stem/precursor cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2:579–583.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Dailey L, Yuan H and Basilico C:

Interaction between a novel F9-specific factor and octamer-binding

proteins is required for cell-type-restricted activity of the

fibroblast growth factor 4 enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 14:7758–7769.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ambrosetti DC, Basilico C and Dailey L:

Synergistic activation of the fibroblast growth factor 4 enhancer

by Sox2 and Oct-3 depends on protein-protein interactions

facilitated by a specific spatial arrangement of factor binding

sites. Mol Cell Biol. 17:6321–6329. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K,

Murakami M, Takahashi K, Maruyama M, Maeda M and Yamanaka S: The

homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in

mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 113:631–642. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Le Doussal V, Coindre JM, Leroux A, Hacene

K, Terrier P, Bui NB, Bonichon F, Collin F, Mandard AM and Contesso

G: Prognostic factors for patients with localized primary malignant

fibrous histiocytoma: a multicenter study of 216 patients with

multivariate analysis. Cancer. 77:1823–1830. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ágoston P, Kliton J, Mátrai Z and Polgár

C: Radiotherapy of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities and

superficial trunk. Magy Onkol. 58:65–76. 2014.In Hungarian.

|

|

47

|

Castillo V, Valenzuela R, Huidobro C,

Contreras HR and Castellon EA: Functional characteristics of cancer

stem cells and their role in drug resistance of prostate cancer.

Int J Oncol. 45:985–994. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ding XW, Wu JH and Jiang CP: ABCG2: a

potential marker of stem cells and novel target in stem cell and

cancer therapy. Life Sci. 86:631–637. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|